I noticed an unusual behavior of the iPhone X home indicator while working on my most recent app. The app’s background near the home indicator is purple. When the app launches, the home indicator is very light gray.

But

something odd happened when I pressed the app’s “share” button, which

opened a default iOS activity view (aka “share sheet”). When I hit the

“cancel” button to close the activity view, the home indicator animated

to a dark gray color.

Even

though the background color was exactly the same, the light-colored

activity view passing underneath caused the home indicator to change

color. The only way to get the home indicator back to its original color

was to leave the app and come back.

I had never seen this before, and it prompted my curiosity.

What

determines the color of the home indicator and why it does it behave

like this? The answer is surprisingly complex. Let’s take a deep dive

and see what we can learn!

Home Indicator Basics

In

September 2017, Apple introduced its newest iteration of mobile phone:

iPhone X. The new design replaced the iconic home button with on-screen

gestures. To go home, the user simply swipes up from the bottom of the

screen.

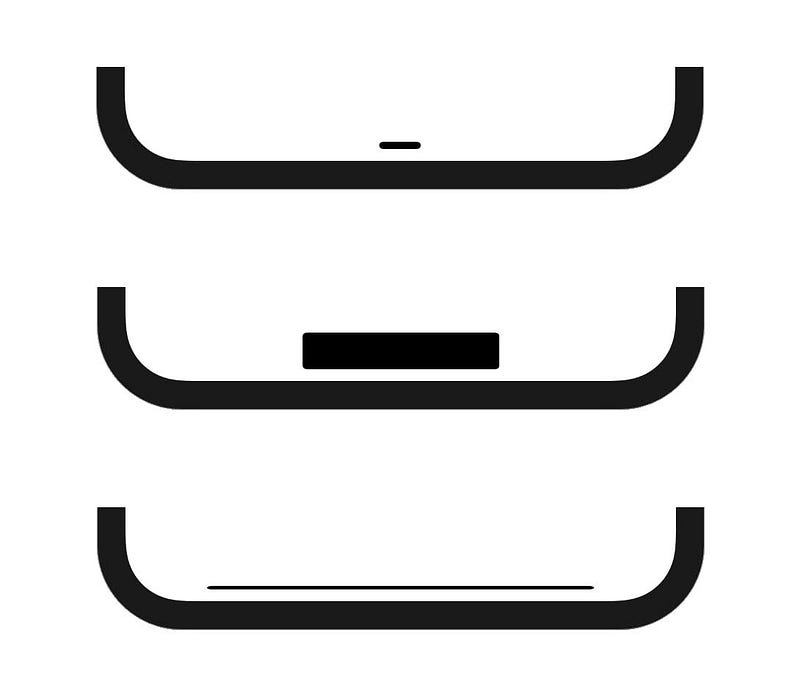

The Home Indicator’s Purpose

To

create the affordance of being able to swipe up from the bottom of the

screen, Apple added a small horizontal bar known as the home indicator.

The home indicator is always present except for the home screen and in

any apps that request it to be temporarily hidden (full-screen video,

games, etc.).

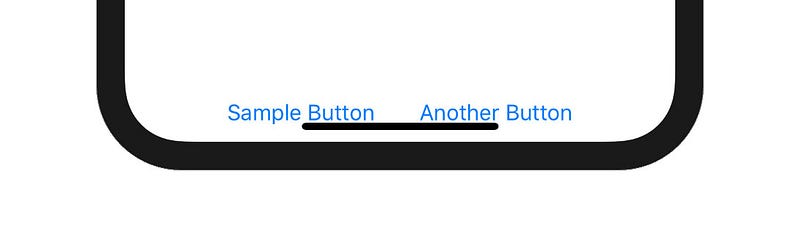

The

home indicator serves another purpose: protecting the bottom edge of

the screen from conflicting user interface elements and gestures.

Because the user needs to be able to swipe up from the bottom of the

screen at any time, best practices now dictate that developers should

avoid place conflicting gestures or buttons in the bottom edge of the

display.

By placing a bar at the bottom, user interface elements in the same location look wrong—there’s

a visual conflict between the bar and other elements. In this sense,

the home indicator “protects” this region of the screen from designers

or engineers that are unaware of the functionality of the iPhone X.

Now that we’re all on the same page, let’s get back to our original question: “What color is the home indicator?”

Part 1 — The Beginning

On September 13, 2017, I answered a Stack Overflow question asking how to change the color of the home indicator.

At

the time, the iPhone X hadn’t been publicly released, but the latest

version of Xcode included an iPhone X simulator. Running a simple test

app in the simulator revealed that the home indicator’s color was based

on the color of the content below it.

The

new APIs for the iPhone X were released alongside this same version of

Xcode, and there was no public API available to modify the color of the

home indicator (which is still the case at the time of writing this

post, and probably will always be the case).

This

made my Stack Overflow answer simple and straightforward: it is not

possible to modify the color, and you shouldn’t worry about it, since

it’s out of your control and guaranteed to be visible.

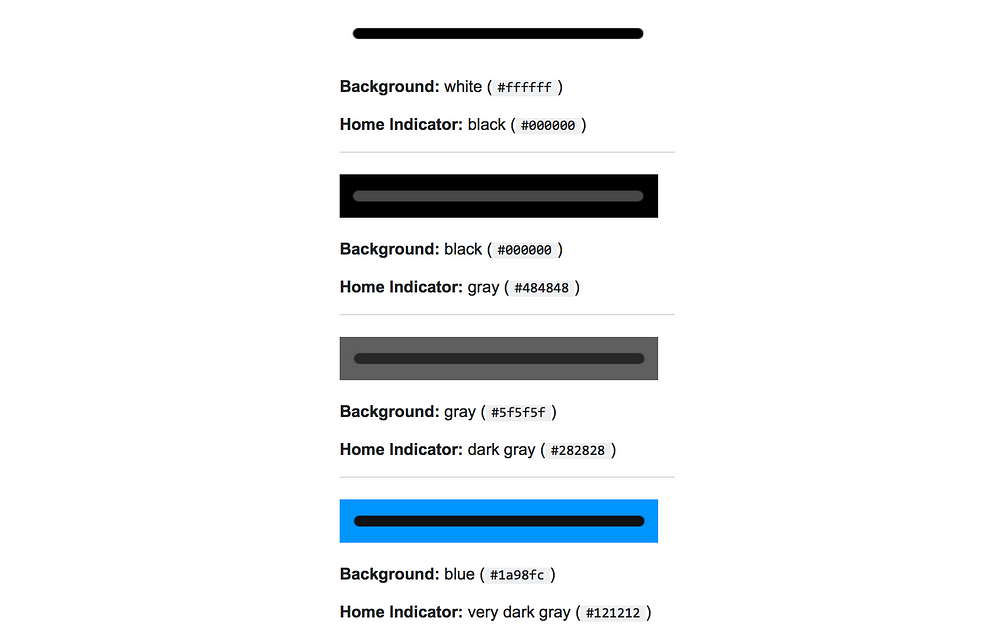

Because

I anticipated this to be a common question, I included some screenshots

of the home indicator on top of various background colors.

This

was good enough for me. The home indicator maintains its visibility by

sampling the color of the view below it, and picking a gray color that

provides sufficient contrast.

Part 2 — The Plot Thickens

It

turns out the home indicator’s color is not that simple. Some further

observations poked holes into my “solid-color function” theory.

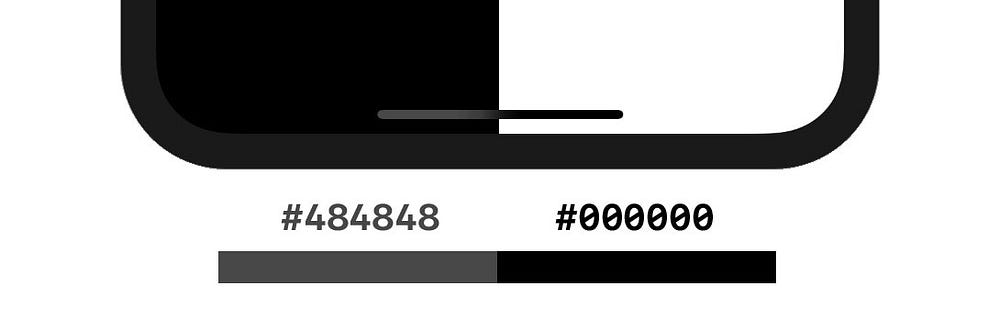

Observation #1: Multiple Colors

The

first observation is that the home indicator can have multiple colors,

similar to a gradient. In the following example, the left side of the

screen is black, and the right is white. The home indicator adjusts for

this by adopting a lighter color over the dark background, and a darker

color over the light background.

The

home indicator can be multiple colors at the same time, and smoothly

transitions between them. This smooth transition is updated in real time

if any of the views behind the home indicator change.

In

the example above, a small white view is moving back and forth behind

the home indicator. The section of the home indicator that covers the

white view becomes pure black and smoothly transitions to gray.

This behavior is similar to a

UIVisualEffectView,

which applies a blur over existing content. The home indicator is most

likely taking a sample of the nearby colors in order to get the blend

effect seen in the image above.

(Besides looking good, this functionality might help prevent burn-in on the OLED display.)

Observation #2: Same Background, Different Home Indicator Color

As

I mentioned at the beginning of this post, I noticed an unusual

behavior when a share sheet passed beneath the home indicator.

This

was the most surprising observation — there is not a simple 1-to-1

mapping between background colors and home indicator colors. At this

point I was determined to learn more via experimentation.

Part 3 — The Investigation Begins

My

first order of business was to determine the formula for the home

indicator color on the iOS simulator. From my previous observations, the

iOS simulator’s behavior was more predictable than a real device.

I

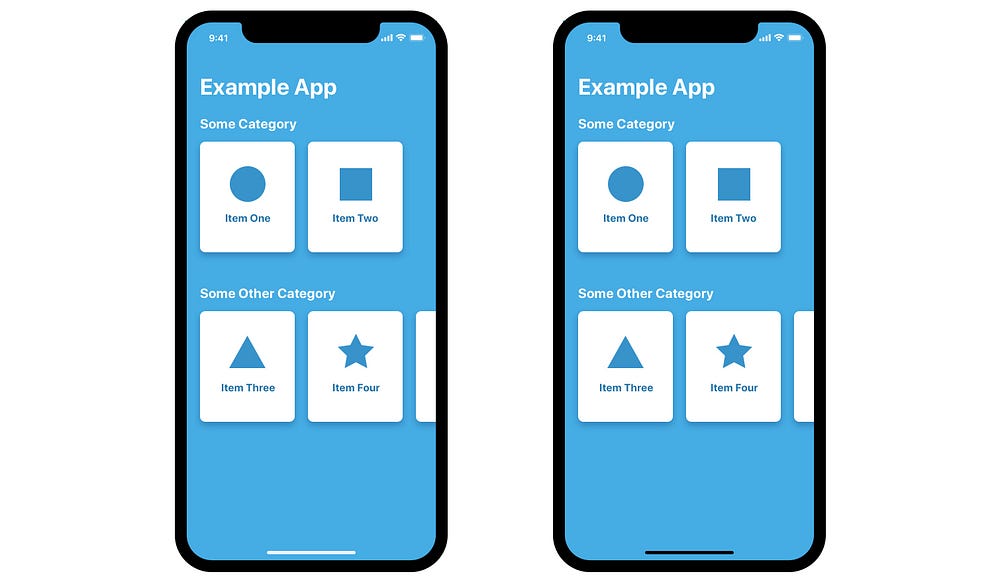

created a new iOS app as a laboratory for my future experiements. The

app was simple—all I needed was an easy way to change the background

color behind the home indicator. A slider and stepper control the

background color’s gray value, which is displayed as a large number in

the center of the screen.

My

goal was to determine the home indicator color for every possible gray

background color. I could graph this data and see if a formula applied

to it. Since there were only 256 possibilities, I took the manual

approach, using macOS’s built-in “Digital Color Meter” app to get the

home indicator color for each value.

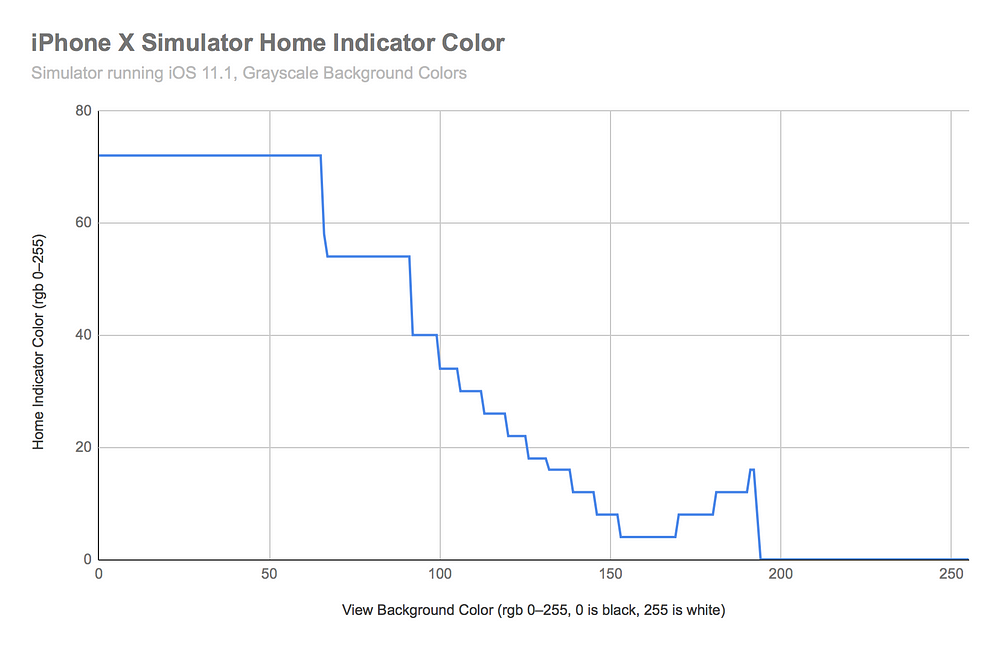

I

graphed the results. It was not a linear function, an exponential

function, or any kind of “nice” function you might see in math class.

The graph was … odd.

This was not what I was expecting.

It

was a step function but with uneven steps. It had a few distinct

sections: a period of (relatively) light gray, two big steps, a series

of small steps, steps in the reverse direction, and a period of pure

black.

The

most unusual part was that the home indicator color was not always

decreasing. There was a period (around rgb 170–190) where it became

lighter as the background became lighter.

Why did the graph look like this? What would the same experiment have similar results on a real device? I needed to know.

Part 4 — The Investigation Continues

My

next task was to perform the same experiment on a real device. It was

immediately obvious that the results were going to be dramatically

different.

To

collect data on a real device, I used the same app from before. I

streamed a live preview of the iPhone screen to my computer via

QuickTime. This removed any discoloration from the True Tone display, as

well as allowed me to use the Digital Color Meter app to easily inspect

the colors.

Another

factor added to the complexity on a real device—the red, green, and

blue values were not always the same. On the simulator, the RGB values

were identical, resulting in colors like RGB(54, 54, 54). On a real

device, they were almost never the same, but were very close, resulting

in colors like RGB(211, 209, 212). When recording the results, I took

the average of the individual RGB values.

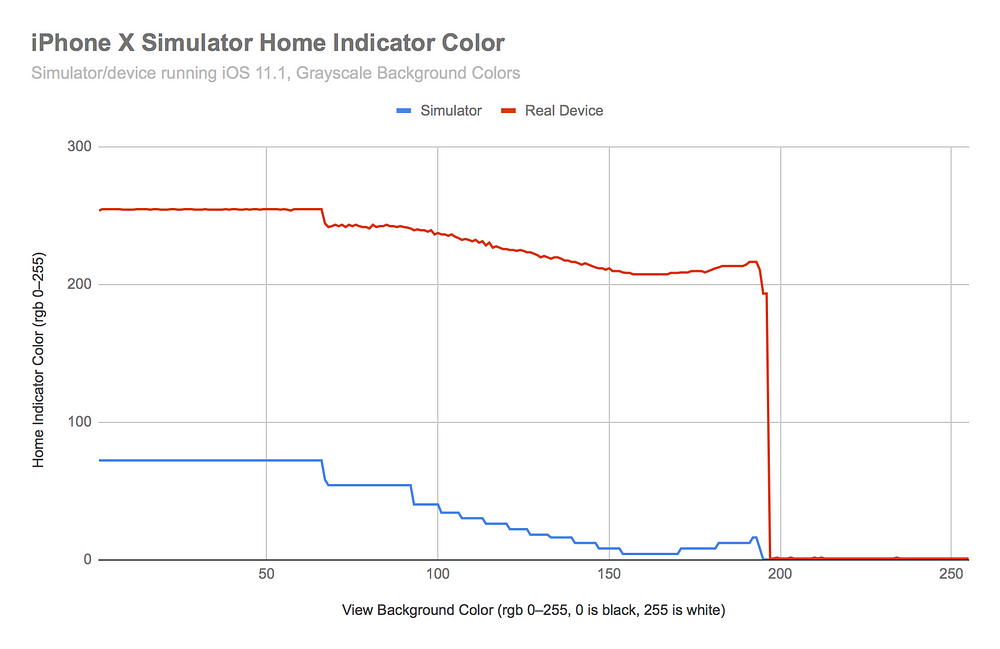

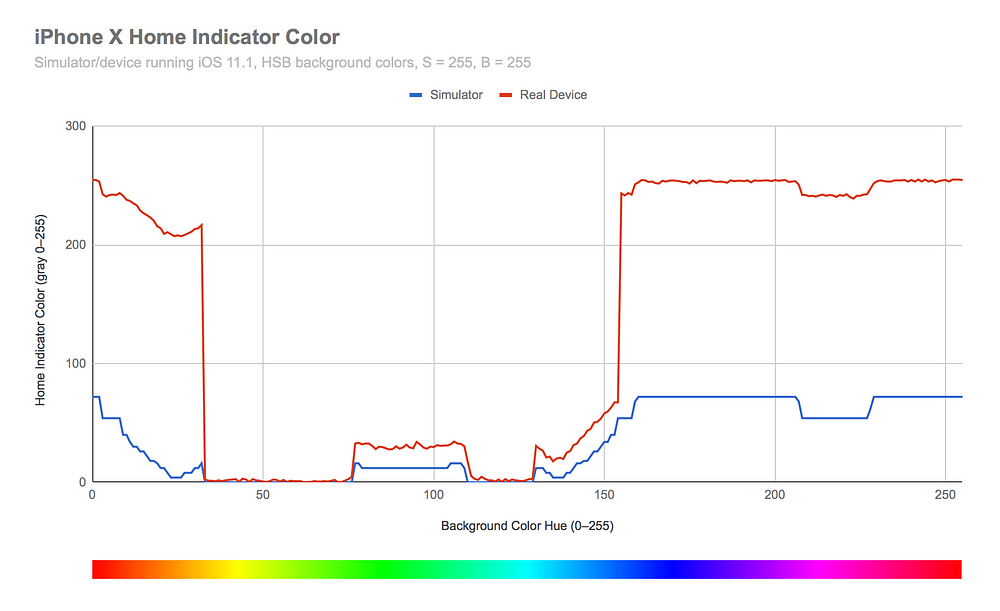

Here are the results, compared with the previous simulator data.

The

colors on a real device (red line) follow a similar trend to those on

the simulator (blue line), except offset by a significant margin. The

simulator home indicator is always very dark, while the device home

indicator is either very light or very dark.

The

graph for the real device is noisy. Overall it follows a smooth trend,

but jumps up and down and looks rough. This is more than just a

side-effect of my averaging, and the noise is consistent. If the

experiment is repeated, the noise follows the exact same pattern.

However, the graph above doesn’t tell the whole story.

The

values presented above were gathered by starting the background

completely black and incrementing the RGB values one at a time (going

from 0 to 255). When the values are gathered in the opposite direction, the results are different.

At

a certain point, the home indicator color “falls off the cliff” in its

transition from light to dark or dark to light, and animates for a brief

period of time, as shown in the previous gif with the purple background

color. Depending on whether the background starts light or dark, the

cliff occurs in a different place.

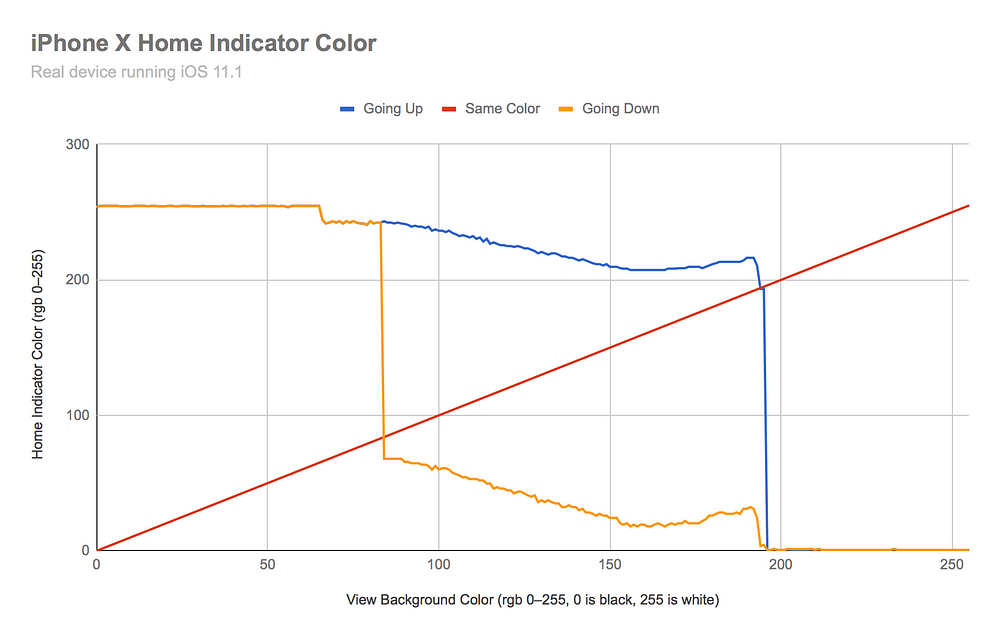

Let’s take a look at a new graph comparing the results from “going up” (black to white) and “going down” (white to black).

The

blue line above is the same as the previous graph’s red line. Its data

points were collected left to right (0 to 255, “going up”). The orange

line is the same data, but collected in the opposite direction (255 to

0, “going down”). The red line represents the points where the home

indicator and the view background are the same color.

The

“going up” and “going down” lines follow a similar path, but have a

different noise pattern. Interestingly, they have the exact same noise

pattern in the darkest range (0–80).

From

this graph we can tell that the “cliffs” occur when the color of the

home indicator is coming too close to the color of the background. It

even appears as if the “going up” and “going down” lines are being

pushed away by the red line, actively trying to resist becoming exactly

the same color as the background. At a certain point, the home indicator

flips to being very dark or very light.

This

explains the shift in color in the app with the purple background. The

purple color must be in a region between the two cliffs. Based on the

previous color of the home indicator, it could either be light or dark.

When the white activity view animates behind the home indicator as it is

dismissed, the home indicator transitions from its light state to its

dark state, and re-settles at the dark-equivelevnt value for the purple

background color.

Part 5 — The Investigation Becomes Colorful

All

the tests up to this point have used grayscale backgrounds. How would

the results differ if we used colored backgrounds instead?

I

repeated the same experiment, but instead of modifying the gray color, I

modified the hue on an HSB color scale. I kept the saturation (S) and

brightness (B) at their maximum values to get the most vibrant and

distinct colors. I only tested these colors “going up”, which in this

case means from hue 0 (red) to hue 255 (red) in rainbow order.

The

first observation is that there are two cliffs — once when the color

becomes yellow, and again when the color becomes dark blue. This occurs

because of the relative “brightness” of the colors.

The

next observation is the difference between the simulator and a real

device. The colors follow the same general trends, but the real device’s

home indicator color is noisier and can reach brighter values.

These

are fascinating findings so far. Aside from testing every possible

background color, there’s not much else we can discover from observation

alone. Now I was curious exactly how the home indicator is

implemented—is it a

UIView? CALayer? UIVisualEffectView? Something else? What is making it behave in this way?

Let’s find out.

Part 6 — We Need to Go Deeper!

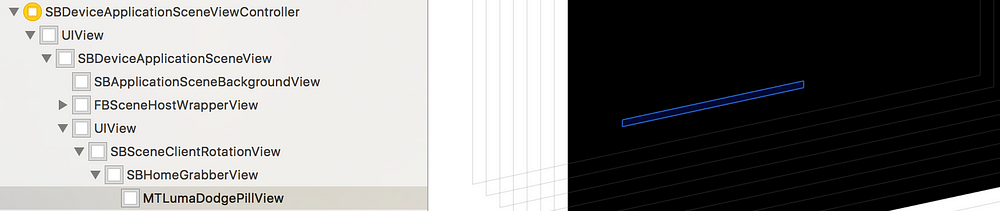

At this point I turned to my friend and iOS expert Ian McDowell.

He was able to point me in the right direction—using the iPhone X

Simulator and Xcode’s debugging tools to find the home indicator.

The

iOS “home screen” is actually an app called SpringBoard. We can attach a

debugger to the Springboard app running in the iPhone X simulator and

use the “Debug View Hierarchy” option in order to inspect the views that

make up the home screen, including the home indicator.

If you want to follow along at home, here is the process:

- Launch an iPhone X simulator.

- In Xcode, select Debug > Attach to Process… > SpringBoard.

- When SpringBoard is running, select the Debug View Heirarchy button.

Deep in the view hierarchy we find an

MTLumaDodgePillView which is a subview of an SBHomeGrabberView. Sounds like we found the home indicator!

The name

MTLumaDodgePillView

makes sense. It confirms our observed behavior of the home indicator,

that its color contrasts the background based on its current brightness.

Can we go deeper yet?

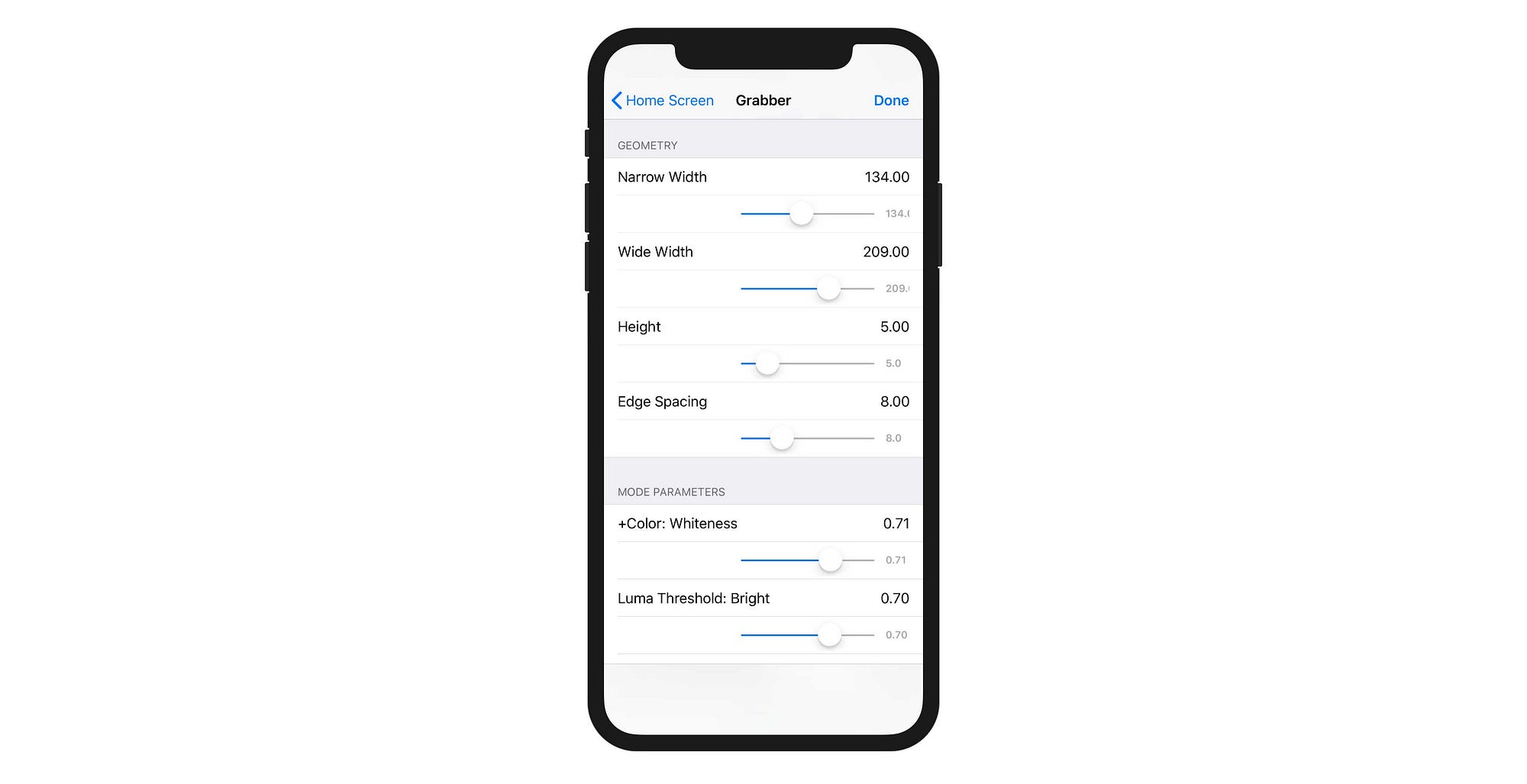

SpringBoard

has another cool feature: a hidden debug menu. It turns out there’s an

entire section for modifying properties of the home indicator. In this

debug menu, the home indicator is called a “grabber”.

This

debug menu mainly contains visual and animation settings. It is most

likely used to collaborate between design and engineering within Apple.

Engineering builds the home indicator, provides hooks to all the

internal parameters, lets designers fiddle with them until they are

content, and then engineers use the settings for the final product.

Luckily for us, we can access this menu and see the results in the simulator.

I

first played around with the visual appearance of the home indicator.

There are sliders for the width and height in various states.

The

other settings are more difficult to test, as they don’t seem to apply

to the simulator. There are settings for a “luma threshold” for light

and dark, as well as parameters for the animation between states. This

confirms the “cliffs” where the color would dramatically animate between

light and dark—there are pre-defined thresholds based on the luminosity

of the background.

I

was unable to determine why the simulator behaves so differently from a

real device. My guess is that the simulator is using a different

combination of settings, or that certain settings only take effect on

real hardware.

Want to learn more about reverse engineering on iOS? Sash Zats posted an amazing in-depth article about the home indicator. Check it out if you want to dive into more code!

This marks the end of the adventure of home indicator discovery. I hope it was as educational for you as it was for me!

High-level Takeaways

- The home indicator’s color is determined by the system and cannot be modified directly.

- The home indicator’s color is determined by the content underneath, and it is not always a solid color.

- The home indicator on the simulator is not an accurate representation of the home indicator on a real device.

- The home indicator animates to its new color(s) when the content underneath changes.

- The home indicator is either in a “light” or “dark” state.

But… Why?

Why bother investigating the home indicator if its appearance is out of our control?

There

is a practical application for these learnings: If a screen in your app

has a background color in the middle range where the home indicator

could be either light or dark, you may prefer one style over the other.

If the status bar is white, for example, it may look more visually

balanced if the home indicator is white as well. Being aware of the home

indicator’s nuanced behavior can help ensure that it doesn’t

accidentally animate between light and dark when it could be distracting

to the user.

In

a previous example, the white share sheet animating behind the home

indicator was enough to change the home indicator’s style.

If

I wanted to prevent this, I could pin a view behind the home indicator

between the safe area and the bottom edge of the display. When the share

sheet is dismissed, I could give it a darker background color (maybe

black with 40% alpha) and add a fade animation so it’s less noticeable.

This

same tactic could be used to set the color of the home

indicator—forcing it over one of the “cliffs”. In the vast majority of

cases, the home indicator should be left alone to do what it wants. Most

iPhone X users have probably already forgotten it’s even there.

The Real Lesson

Hopefully

this brief investigation into the color of the home indicator helps us

appreciate the complexity of simple design. “It’s just a black/white

bar!” is far from the truth. The amount of care and attention to detail

that went into the home indicator is worth appreciating.

Taking

something simple, investigating its internal complexities, and

pondering its design helps us learn about the creative process. By

combining design and engineering, we can make better products that are

simple and delightful to use.

No comments:

Write comments