Progressive Web Apps (PWA) are the latest trend in mobile application development using web technologies. At the time of writing (early 2018), they’re only applicable to Android devices.

PWAs are coming to iOS 11.3 and macOS 10.13.4, very soon.

WebKit,

the tech underlying Safari and Mobile Safari, has recently (Aug 2017)

declared that they’ve started working on introducing Service Workers

into the browser. This means that soon they will land in iOS devices as

well. So the Progressive Web Apps concept will likely be applicable to

iPhones and iPads, if Apple decides to encourage this approach.

It’s

not a groundbreaking new technology, but rather a new term that

identifies a bundle of techniques that have the goal of creating a

better experience for web-based apps.

What is a Progressive Web App

A Progressive Web App is an app that can provide additional features based on what the device supports, providing offline capability, push notifications, an almost native app look and speed, and local caching of resources.

This

technique was originally introduced by Google in 2015, and proves to

bring many advantages to both the developer and the users.

Developers have access to building almost-first-class

applications using a web stack. This is always considerably easier and

cheaper than building native applications, especially when considering

the implications of building and maintaining cross-platform apps.

Devs can benefit from a reduced installation friction,

and at a time when having an app in the store does not actually bring

anything in terms of discoverability for 99,99% of the apps, Google

search can provide the same benefits if not more.

A

Progressive Web App is a website which is developed with certain

technologies that make the mobile experience much more pleasant than a

normal mobile-optimized website. It almost feels like working on a

native app, as it offers the following features:

- Offline support

- Loads fast

- Is secure

- Is capable of emitting push notifications

- Has an immersive, full-screen user experience without the URL bar

Mobile

platforms (Android at the time of writing, but it’s not technically

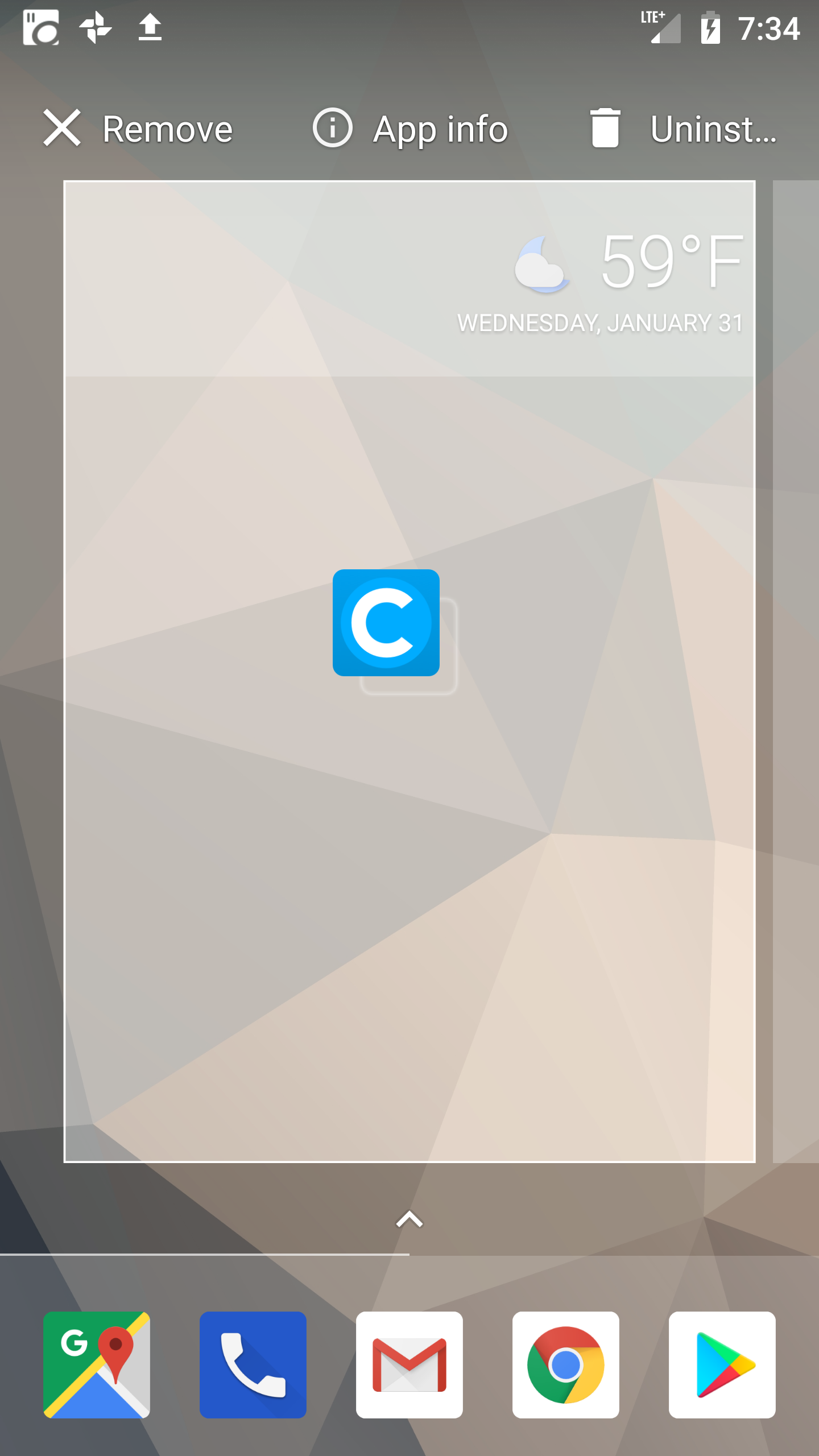

limited to that) offer increasing support for Progressive Web Apps. They

even ask the user to add the app to the home screen when that user visits such a site.

But first, a little clarification on the name. Progressive Web App can be a confusing term,

and a good definition is: web apps that take advantage of modern

browsers features (like web workers and the web app manifest) to let

their mobile devices “upgrade” the app to the role of a first-class

citizen app.

Progressive Web Apps alternatives

How does a PWA stand compared to the alternatives when it comes to building a mobile experience?

Let’s focus on the pros and cons of each, and let’s see where PWAs are a good fit.

Native Mobile Apps

Native

mobile apps are the most obvious way to build a mobile app. Objective-C

or Swift on iOS, Java /Kotlin on Android and C# on Windows Phone.

Each

platform has its own UI and UX conventions, and the native widgets

provide the experience that the user expects. They can be deployed and

distributed through the platform App Store.

The

main pain point with native apps is that cross-platform development

requires learning, mastering and keeping up to date with many different

methodologies and best practices. If, for example, you have a small team

or you’re a solo developer building an app on 3 platforms, you need to

spend a lot of time learning the technology and environment. You’ll also

spend a lot of time managing different libraries and using different

workflows (for example, iCloud only works on iOS devices — there’s no

Android version).

Hybrid Apps

Hybrid

applications are built using Web Technologies, but are deployed to the

App Store. In the middle sits a framework or some way to package the

application so it’s possible to send it for review to the traditional

App Store.

Some

of the most common platforms are Phonegap and Ionic Framework, among

many others, and usually what you see on the page is a WebView that

essentially loads a local website.

I initially included Xamarin in the list, but Carlos Eduardo Pérez correctly pointed out that Xamaring generates native code.

The key aspect of Hybrid Apps is the write once, run anywhere

concept. The different platform code is generated at build time, and

you’re building apps using JavaScript, HTML and CSS, which is amazing.

The device capabilities (microphone, camera, network, gps…) are exposed

through JavaScript APIs.

The

bad part of building hybrid apps is that, unless you do a great job,

you might settle on providing a common denominator. This effectively

creates an app that’s sub-optimal on all platforms because the app is

ignoring the platform-specific human-computer interaction guidelines.

Also, performance for complex views might suffer.

Apps built with React Native

React

Native exposes the native controls of the mobile device through a

JavaScript API, but you’re effectively creating a native application,

not embedding a website inside a WebView.

Their motto, to distinguish this approach from hybrid apps, is learn once, write anywhere. This

means that the approach is the same across platforms, but you’re going

to create completely separate apps in order to provide a great

experience on each platform.

Performance

is comparable to native apps, since what you build is essentially a

native app which is distributed through the App Store.

Progressive Web Apps features

In the last section, you saw the main competitors of Progressive Web Apps. So how do PWAs stand compared to them, and what are their main features?

Remember — currently, Progressive Web Apps are for Android devices only.

Features

Progressive Web Apps have one thing that separates them completely from the above approaches: they are not deployed to the app store.

This

is a key advantage. The app store is beneficial if you have the reach

and luck to be featured, which can make your app go viral. But unless

you’re in the top 0.001% you’re not going to get much benefit from

having your little place on the App Store.

Progressive Web Apps are discoverable using Search Engines, and when a user gets to your site that has PWAs capabilities, the browser in combination with the device asks the user if they want to install the app to the home screen. This is huge, because regular SEO can apply to your PWA, leading to much less reliance on paid acquisition.

Not being in the App Store means you don’t need Apple’s or Google’s approval

to be in the users pockets. You can release updates when you want,

without having to go through the standard approval process which is

typical of iOS apps.

PWAs

are basically HTML5 applications/responsive websites on steroids, with

some key technologies that were recently introduced to make some of the

key features possible. If you remember, the original iPhone came without

the option to develop native apps. Developers were told to develop

HTML5 mobile apps that could be installed to the home screen, but the

tech back then was not ready for this.

Progressive Web Apps run offline.

The use of service workers allow the app to always have fresh content, which can be downloaded in the background, and to provide support for push notifications, which offer greater re-engagement opportunities.

Also, sharability makes for a much nicer experience for users that want to share your app, as they just need a URL.

Benefits

So why should users and developers care about Progressive Web Apps?

- PWA are lighter. Native Apps can weigh 200MB or more, while a PWA could be in the range of the KBs.

- There’s no native platform code

- The

cost of acquisition is lower (it’s much more difficult to convince a

user to install an app than to visit a website to get the first-time

experience)

- Significantly less effort is needed to build and release updates

- They have much more support for deep links than regular app-store apps

Core concepts

- Responsive: the UI adapts to the device screen size

- App-like feel: it doesn’t feel like a website but rather like an app (as much as possible)

- Offline support: it will use the device storage to provide an offline experience

- Installable: the device browser prompts the user to install your app

- Re-engaging: push notifications help users re-discover your app once installed

- Discoverable: search engines and SEO optimization can provide a lot more users than the app store

- Fresh: the app updates itself and the content once it’s online

- Safe: it uses HTTPS

- Progressive: it will work on any device, even older one, even if it has fewer features (e.g. just as a website, not installable)

- Linkable: it’s easy to point to it using URLs

Service Workers

Part of the Progressive Web App definition is that it must work offline.

Since the thing that allows the web app to work offline is the Service Worker, this implies that Service Workers are a mandatory part of a Progressive Web App.

TIP: Don’t confuse Service Workers with Web Workers. They are a completely different thing.

A

Service Worker is a JavaScript file that acts as a middleman between

the web app and the network. Because of this it can provide cache

services, speed the app rendering, and improve the user experience.

For

security reasons, only HTTPS sites can make use of Service Workers, and

this is part of the reason why a Progressive Web App must be served

through HTTPS.

Service

Workers are not available on the device the first time the user visits

the app. On the first visit the web worker is installed, and then on

subsequent visits to separate pages of the site, this Service Worker

will be called.

The App Manifest

The App Manifest is a JSON file that you can use to provide the device information about your Progressive Web App.

You add a link to the manifest in every header on each page of your web site:

<link rel="manifest" href="/manifest.json">

This file will tell the device how to set:

- The name and short name of the app

- The icons’ locations, in various sizes

- The starting URL, relative to the domain

- The default orientation

- The splash screen

Example

{

"name": "The Weather App",

"short_name": "Weather",

"description": "Progressive Web App Example",

"icons": [{

"src": "images/icons/icon-128x128.png",

"sizes": "128x128",

"type": "image/png"

}, {

"src": "images/icons/icon-144x144.png",

"sizes": "144x144",

"type": "image/png"

}, {

"src": "images/icons/icon-152x152.png",

"sizes": "152x152",

"type": "image/png"

}, {

"src": "images/icons/icon-192x192.png",

"sizes": "192x192",

"type": "image/png"

}, {

"src": "images/icons/icon-256x256.png",

"sizes": "256x256",

"type": "image/png"

}],

"start_url": "/index.html?utm_source=app_manifest",

"orientation": "portrait",

"display": "standalone",

"background_color": "#3E4EB8",

"theme_color": "#2F3BA2"

}

The App Shell

The App Shell is not a technology but rather a design concept.

It’s aimed at loading and rendering the web app container first, and

the actual content shortly after, to give the user a nice app-like

impression.

Take,

for example, Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines’ suggestion to use a

splash screen that resembles the user interface. This provides a

psychological hint that was found to lower the perception that the app

was taking a long time to load.

Caching

The

App Shell is cached separately from the contents, and it’s setup so

that retrieving the shell building blocks from the cache takes very

little time.