The Future of Light

Edison’s

commercialization of the electric light bulb quite literally changed

the world. His technology helped enable the power grid, modern

transportation, and ultimately the lifestyles we enjoy today. Lighting

improved gradually over the last century until the recent mass adoption

of LEDs.

As

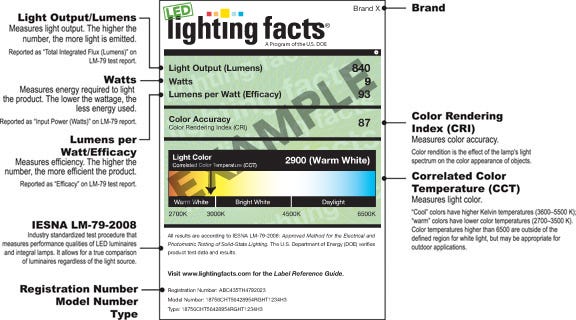

LED lighting goes mainstream, we face new challenges. You can no longer

buy a 60 Watt bulb. Instead, you have to dive deep on CCT, CRI, lumens,

and other jargon. There is an increased awareness of the risks of blue

light coupled with unwarranted demonization of the new technology. The

lighting industry as a whole faces stagnation.

How do we get out of this mess, and where do we go from here?

The LED Revolution

Red

and green LEDs have been around for about 50 years, mostly confined to

use as indicator lights in electronics. In the early 90s, three Japanese

researchers at Nagoya University and Nichia Chemical created the first

blue light emitting diode (LED) from gallium nitride (GaN).

The

discovery by Nobel recipients Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano, and Shuji

Nakamura was significant because blue light can be converted to white

light by means of a phosphor material. The phosphor material, for

example yttrium aluminium garnet (YAG), is generally yellow in color and

sits atop the LED die material.

In

the mid-2000s, companies started packaging blue LEDs and phosphors into

bulbs and other light sources. These early products were expensive

($20-$50 for a bulb) and largely had problems with color consistency,

heat, and lifetime.

Today, you can buy an LED bulb for about $1.50.

The cost of components dropped, along with increases in performance. According to Haitz’s law, the cost per lumen (an amount of emitted light) decreases by a factor of 10 each decade.

Today, you can buy an LED bulb for about $1.50.

That bulb has better color performance than its swirly compact

fluorescent equivalent, and lasts 10,000–20,000 hours. Other LED sources

can last significantly longer (50,000–100,000 hours). By contrast, an

incandescent bulb may last 1,000–2,000 hours.

LED

lamps are not far off in price from incandescent lamps at the point of

sale. But their long lifetimes and low power usage mean you can save

significantly more. Over the life of a cheap LED bulb, you will pay

about $12, including the purchase price and energy. Five 60 Watt

incandescent bulbs would cost about $78 over the same period of time.

And don’t forget that you have to change the bulb five times instead of

just once.

Efforts have been made to phase out the sale of incandescent bulbs in numerous countries. Even though legislation has not passed in some places, the lighting industry has largely moved on to LED anyway. IKEA became the first large retailer to sell only LED lighting in 2015, and others are making similar moves.

The efforts are working. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, LED market penetration was 12.6% in 2016. That’s up from just 3% in 2014.

Massive Choice, Massive Confusion

All

is not well. LED had its moment of differentiation, but now it’s

largely a race to the bottom in price. That $1.50 bulb purchase will

happen one-fifth as often, breaking old business models. The old

stalwarts struggle to compete with new discount-oriented brands.

General Electric, the company Thomas Edison founded, plans to sell its bulb business due to low profit margins.

People just want their 60 Watt bulb back, energy savings be damned.

It’s

not even all that great for consumers. That LED bulb is cheap, but you

probably don’t really know what you’re getting. The Home Depot and other

retail outlets don’t do a good job of explaining color temperature

(CCT), lumens, and color rendering index (CRI). Manufacturers fuel the

confusion with misleading terms like “soft white” and “bright white.”

Early LED products were plagued with reliability issues and ugly color, further contributing to the stigma.

Oh, you want to use that bulb with your existing dimmer? Forget about it.

All

of this leads to mass dissatisfaction. And dissatisfaction results in

returns, which does not help the already low-margin consumer lighting

business. People just want their 60 Watt bulb back, energy savings be

damned.

Things

are a bit brighter in the commercial sector. LED fixtures are available

in a million shapes, sizes, and colors. Energy and maintenance costs

are drastically reduced, improving a building’s bottom line.

Most

commercial LED fixtures have no lamps to replace. They are intended to

last until the next renovation. Barring any electronics failures, LEDs

don’t “burn out.” They just get dimmer over time.

But the B2B sector also has its issues. Lighting controls are increasingly requested, and in some cases even required by law.

Very few manufacturers make all the components of a lighting system,

leading to incompatibilities. Even when the stars align, it can be

extremely costly and time-consuming to commission the system as

intended.

The DLC standard

focuses so much on energy efficiency that it may ultimately impair

quality of light. California, historically the most progressive state in

energy regulations, has fought back, putting a higher emphasis on color performance than energy. LEDs are efficient enough, they say. But the state is now under scrutiny for overriding federal energy efficiency regulations.

Blue Light Blues

At

the same time, we have become aware of the effects of light on the

human circadian rhythm. There’s debate about the nuances, but in

general, you can sleep better and perform better when there is

significant blue light during the day and very little at night.

In addition to the rods and cones, there is a third type

of photoreceptor in our eyes that is only sensitive to blue light.

Instead of contributing to vision, these cells tell the body clock when

it is daytime and when it is not.

This

mechanism worked well up until the last 150 years or so, before

electric lighting became ubiquitous. The same lighting found in our

homes and electronic devices can trick the body clock into thinking it’s

daytime when it is really not.

It’s not like the issue is limited to academics. People are aware of the effects of blue light, and want solutions.

Circadian

rhythm disruption may seem like a first world problem, less important

than public health issues related to malnutrition and poverty. But it

has been linked to breast cancer, Alzheimer’s disease,

and other conditions. Additionally, shift work and frequent time zone

hopping can contribute to accidents on and off the job, as well as

inconsistent menstrual cycles in females.

Apple is the only household name to have taken a significant stance on this problem, with the introduction of Night Shift

on iOS in early 2016 and on MacOS in 2017. Night Shift changes phone

and computer screens to an orange hue at night, reducing the blue light

content. Even then, the feature is not enabled by default and not widely

advertised by the company.

Anecdotally,

I was in an Apple Store recently. A little old lady came up to one of

the employees and asked how to get the orange light back on her phone.

It’s not like the issue is limited to academics. People are aware of the

effects of blue light, and want solutions.

The

lighting industry, in general, has made little progress in providing

straightforward products that address circadian disruption. The

specification community, which includes lighting designers and

architects, is begging for systems that support their latest

human-centric designs. But their pleas mostly fall on deaf ears.

The

industry’s arguments du jour against human-centric lighting circle

around: not enough research, disagreements on the spectrum of light, and

complexity of integrated systems. In my opinion, these are excuses to

avoid pioneering in an unverified market.

The

lighting giants are blind to the potential of human-centric lighting to

differentiate their businesses. There is room for someone to come in

and make a big splash.

Circadian Lighting

Several

upstarts have created a category that I call circadian lighting.

Broadly speaking, circadian lighting shifts in color and brightness

automatically throughout the day. The morning begins with a warm, dim

glow, giving way to cool, bright light during working hours. In the

evening, the lighting shifts back to a warm glow. It’s a lot like f.lux and Night Shift, but for your environment.

One of the most notable startups in this category is Ketra,

which makes a circadian lighting system that can be installed in the

home and commercial environments. It’s not particularly affordable, but

the Ketra system is the most complete and ready-to-go out of the box

circadian lighting solution at the moment.

Not

only does circadian lighting match the science, but it also just feels

right. Cool, relatively bright lighting during the day makes the indoor

environment seem more like outside. In the evening, dimmer, warmer light

promotes relaxation. Waking up in the middle of the night, only very

dim light is needed to guide the way. Otherwise, the light would

startle.

Ketra’s

offering is by far the most impressive, but there are signs of light

from other manufacturers. Philips offers an LED bulb for about $6

that can change between three color settings (dim and warm at night,

normal bright incandescent, and cool, bright white for the day) simply

by flicking a switch. IKEA has something similar but with wireless

remote controls and dimming for $27.

These

products can only be controlled manually, and thus are not true

circadian lighting. But they are something you can buy today for not a

lot of money to get a glimpse into the future.

Light Tuned to You

Circadian

lighting sounds great, but what about all the other factors that can

influence the circadian rhythm? What about food, social events,

caffeine, alcohol, stress, and travel?

A

lighting system is unlikely to counteract circadian disruption

completely. However, if it knows about your circadian state, the

lighting could help normalize the body’s cycle of sleep and wake.

The lighting in your environment would always be the right light for you.

Let’s

say you’re traveling to Tokyo in a week. Your destination is 13 hours

ahead of Eastern Daylight Time. Instead of throwing your circadian

rhythm into a complete 180 upon arrival, circadian lighting could help

you shift to the new time zone in the days leading up.

Or

you’re a shift worker on the night shift. But you also have weekend

activities planned with your family, most of which take place during the

day. Circadian lighting could help reduce the grogginess associated

with rapidly changing sleep patterns.

What

if the lighting in your home, car, office, and gym was tuned to your

circadian rhythm? What if the light at your desk was different from the

light at your neighbor’s desk? What about the lighting in your airplane

seat and the hotel room or Airbnb thousands of miles away?

What if the lighting system knows not only that someone is present in a room, but also who

that happens to be? The lighting in your environment would always be

the right light for you. You never would have to do much more than dim

the lights, and maybe not even that.

Building the Killer App

LED

lighting quickly moved from an expensive toy for early adopters to a

cheap commodity. Now there is room for a killer app, and I believe

advanced, connected circadian lighting is the answer.

A great product is simple, understandable, and affordable.

The pieces of the puzzle already exist to make all of this happen. A combination of GPS and an indoor positioning system can pinpoint your precise location anywhere in the world. Info about your sleep hygiene could come from a Fitbit or smartwatch. A phase response curve would be applied to shift your circadian rhythm by the amount appropriate at any given time.

Whoever

builds a circadian lighting solution will recognize that it is no easy

feat. It takes an understanding that a great product is simple,

understandable, and affordable. It takes the right people working toward

a uniform, opinionated vision.

We’ve

seen the potential of circadian lighting to positively impact people’s

lives. The awareness is there, and will continue to grow.

Now we’re just waiting for the right solution.