What It Takes to Train The Next Generation of Innovators

This article was published on GrowthX Academy’s Blog on August 28, 2017.

Sean Sheppard, founder of GrowthX Academy, discusses the critical skills for the upcoming “Innovation Economy”.

“How

do we educate people for a future we can’t predict?” It’s a question

that’s been on my mind a lot lately — and, it turns out, it’s been on Sean Sheppard‘s as well.

Sean is a serial entrepreneur, venture capitalist, and the founder of GrowthX

and the GrowthX Academy. He’s someone who’s been steeped in modern

sales, marketing and growth hacking methods, so I was excited to get the

chance to chat with him recently about the skills he believes will be

critical for the coming “Innovation Economy.”

The Problem: Our Outdated Education System

Most

of us have the sense that our education systems haven’t kept pace with

innovation. In our conversation, Sean explains how deeply behind we’ve

fallen:

“The modern education system was developed in the Age of Enlightenment to support the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century as a way to take people off of farms and educate them to work in factories. That’s why there are school bells. They’re meant to mimic factory whistles. That’s why we have the people lined up in desks, in rows, because that’s how an assembly line is constructed.”

As

Sean notes, this transition was critical. “In the 1900s, 40 percent of

the jobs in this country were farming jobs. Today, only 2 percent are

farming jobs.” Moving from an agriculture-driven society to an

industrial one required education systems that prepared students for the

kinds of jobs that were becoming available.

Sean

points out that we’re in a similar transition now. “Very soon, 40 to 50

percent of the jobs are going to be replaced by robots and automation.

We’re now entering what the World Economic Forum has called the fourth

industrial revolution: the ‘Innovation Economy.’”

The Four Factors of Future Effectiveness

So

what changes do we need to make to prepare for this coming transition?

What skills do students and professionals need to practice today to

build competency for future jobs? Sean highlights four pillars in

particular that form the basis of his approach at GrowthX (I’ll give you

a hint — none of them involve getting an MBA or liberal arts degree).

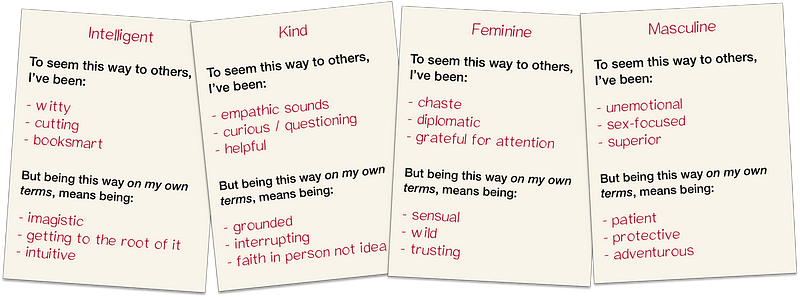

1. Mindset

I

was happy to hear Sean touch on mindset as one of his four pillars, as

it’s something I’ve been hammering into my team at Web Profits. Sean and

I agree — the future belongs to those who adopt a growth mindset,

rather than a fixed mindset.

None

of us can predict with 100% certainty what the future of the Innovation

Economy looks like (except maybe Mark Zuckerberg). Limiting yourself

with a fixed mindset — one that restricts you to considering things as

they are, not as they might be — could prevent you from identifying and

taking advantage of opportunities as they arise.

That’s

somewhat obvious, but Sean added an important note: “There is no

distinction between personal and professional development in the

Innovation Economy.” You can’t think of your future performance in terms

of your career alone. Embracing the growth mindset Sean suggests means

recognizing that every part of yourself — from your work to your health

and beyond — can, and should, be improved upon.

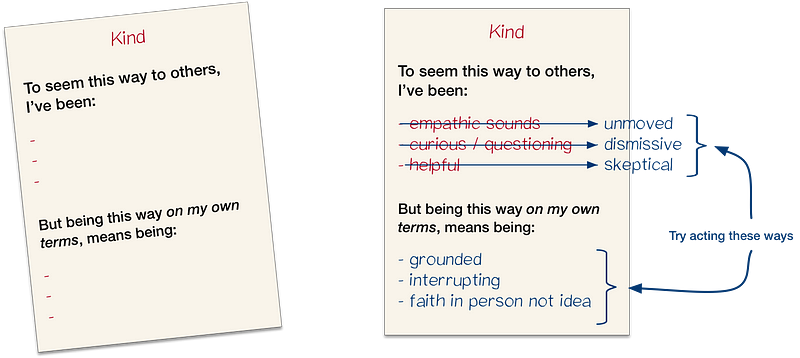

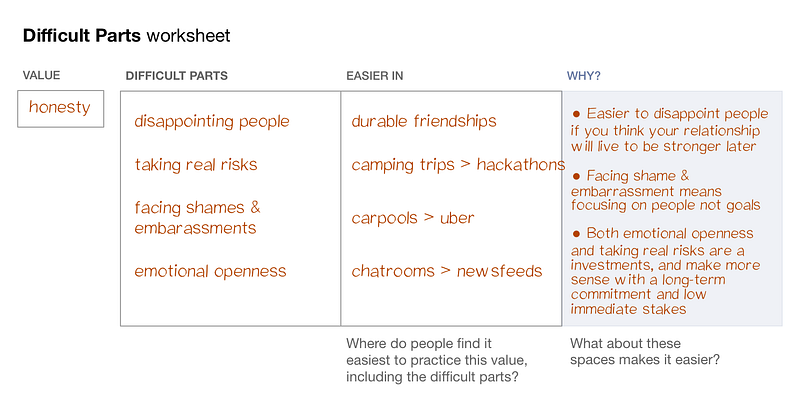

2. Mastery

Having

a growth-based mindset provides needed flexibility for an unclear

future. But mindset alone doesn’t fully answer the question of how you

prepare today for jobs that may not exist until tomorrow.

That’s

where competency-based education comes into play, according to Sean.

“Competency-based education models will be the future of education. It’s

the idea that we can measure people the same way you and I measure

marketing efforts in real-time. We can assess people quickly about

whether or not they’ve achieved the competency.”

Out

of competency, Sean suggests, mastery grows. “You acquire the

knowledge; there’s a framework for that. You practice it to demonstrate

that you can acquire the competencies, and then through the repetitive

iteration of that, you develop proficiency and then, ultimately,

mastery.”

Sean’s

model makes more sense when applied to a hypothetical job. Suppose you

want to become a growth hacker. There’s no “official” training program;

no university you can attend. So how do you prepare for this job?

According to Sean, you study the existing knowledge that’s available.

You identify and develop the core competencies involved in the job.

Then, through practice, iterative improvement and the simple investment

of time, you eventually achieve mastery.

The

beauty of this approach is that it’s available to everyone. Sean

states, “It’s about being a learn-it-all not a know-it-all. It’s about

understanding that the foundation of mastery is that you do not have to

be born with some natural level of inborn talent or set of skills.”

3. Career

Transforming

personal and professional mastery into a career will look different

than it used to, according to Sean. “As an individual you have to focus

on your career development, and as a manager and a leader, you have to

focus on helping people develop their careers.”

Long

tenures with a single company are practically nonexistent these days,

and our transition to the Innovation Economy will only accelerate this

change. Succeeding in this future — in whatever role you define

yourself — will require that you take an active role in managing your

career, as well as helping guide the careers of others.

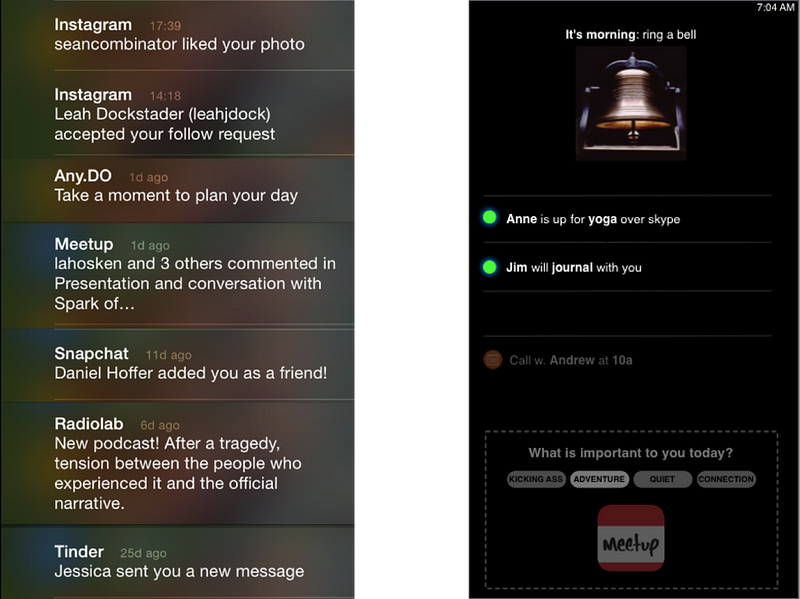

4. Community

Mindset,

mastery and career are all factors you develop on your own. But, in

Sean’s opinion, where things really come together is in a focus on

community. “The modern education requires diversity of thought, opinion,

background, and experience from a whole host of different points of

view.”

Simply

put: you need a diverse community whose wisdom you can draw on to

advance your learning beyond what you’re capable of on your own.

Sean attempts to build communities like these through GrowthX (the

next session starts September 12th), but you can also cultivate your

own community by connecting with older mentors, those in other

industries and thought leaders you admire.

Now

isn’t the time to remain idle. By focusing on updating your mindset,

mastery, career and community, you’ll be ready to face whatever

challenges come your way in the new Innovation Economy.

This article was published on GrowthX Academy’s Blog on August 28, 2017.