What voice tech means for brands

An overview of the issues around voice technology and top line considerations for brand owners.

Summary

Voice

based technology is going to have a huge impact on many sectors, with

50% of all search forecast to be voice-based within just two years. The

rate of uptake is likely to vary based on age, geography and

literacy — but some markets and platforms already have high penetration,

while globally 10% of search is already voice based.

There

will be new winners and losers in this space, and incumbent brands will

need to look at the impact of losing control of the consumer

conversation during the purchase process, making it harder to stand out

against their competition.

However,

voice interfaces give an unprecedented opportunity for brands to

interact with consumers in an extremely powerful new way, and few brands

have taken advantage of this yet. Current widely-available

functionality is limited in scope and very utility-focused; there are

opportunities to develop innovative content and experiences as well as

whole new services.

The

brands that rise to the occasion are in a good position to increase

their market share. Additionally, there are many tools available

allowing easy experimentation with voice for minimal investment.

Our

recommendation is to start a low investment program of service design

and Tone of Voice experimentation as soon as possible — possibly tied in

to campaign activity — in order to prepare your brand to take advantage

of opportunities that this technology reveals.

Introduction

What do we mean by ‘Voice’?

In

the context of this article, we mean ‘talking out loud to automated

services’. This covers everything from interactive fiction to utilities,

available on bespoke hardware devices, within apps on phones and in the

cloud, either accessed via a branded product or one of the major

players’ virtual assistants.

A lot of the hype around voice revolves around the uptake of smart speakers (75% of US households are projected to own one by 2020),

and the ‘voice assistants’ that come with them. Several of these

assistants now allow direct third party integration, a bit like apps on a

smartphone.

In

addition, it’s important to note that these and other voice assistants

are available on other hardware — often phones and tablets, via apps and

deep OS integrations, but also bespoke hardware devices and even

websites.

In

many respects the technologies underlying voice and bots are the

same — but the ecosystems and impact are different enough to have made

voice very much its own area.

Is voice just hype?

No.

It’s true that there is a lot of hype about voice, and that it looks

similar to 3D printing and other ‘technologies that will change the way

we live’, but interacting with computers via voice interfaces is here to

stay.

Apart from anything else there are a range of convincing statistics; for example over 20% of mobile search is already voice based and forecast to rise to 50% of all search by 2020.

Perhaps more interestingly, there are some reasons behind those statistics that might be telling.

It’s often said in technology circles that the majority of next billion people due to get online

for the first time will be poorly educated and likely illiterate, as

‘underdeveloped’ nations start to get internet access. For this

demographic video and voice will be paramount — and voice may be the

only two-way medium available to them.

Additionally,

the iPad effect revealed how even very young children could interact

with a touchscreen while struggling with a mouse; voice interaction is

even faster and more intuitive (once someone can talk) and will

undoubtedly be the primary interaction method for some functions within a

few years.

It’s

also worth considering the stakes involved, especially for Google and

Amazon, the biggest players in ad revenue and organic product discovery

respectively. Amazon’s aggressive move into voice will already be having

a noticeable effect on Google’s bottom line by moving search away from

the web and Google ads’ reach— which explains why the latter is working

so hard to make a success of its own Assistant.

To

their advantage Google can leverage their existing 2.5Bn Android

devices in the wild. With numbers that big and uptake gaining traction

you can understand the predicted total of 7.5Bn installed voice assistants in operation by 2021.

Concerns about privacy and security do slow adoption in some respects, which we explore later in this article.

A

common argument against voice is the social oddness or ‘embarrassment

factor’ of talking out loud to a device, especially in a public place

(and especially by older people — by which we mean anyone over 20

really). BBH’s view on this is that these norms are fast to change; for

example a decade ago it was unthinkable to put a phone on a dinner table

in most situations; these days it can be a sign of giving undivided

attention (depending on nuance), or it can even be acceptable to answer a

call or write a text during a meal in some circumstances.

Overview

Voice is quickly carving a space in the overall mix of technological touchpoints for products and services.

In many ways, this is not surprising; using our voices to communicate is three times faster, and significantly easier

than typing. It’s so natural that it takes only 30 minutes for users to

relax with this entirely new interface, despite it bringing a freight

of new social norms.

There

are also contexts in which voice simply beats non-voice input methods;

with wet or full hands (cooking, showering), with eyes being used for

something else (driving) or almost anything for those of us whose use of

hands or eyes may be limited.

While

voice is unlikely to completely replace text in the foreseeable future,

it will undoubtedly have a big impact in many technology-related

fields, notably including e-commerce and search.

A brief history of voice

Automated

voice-based interfaces have been around for decades now although their

most influential exposure has been on customer service phone lines. Most

of the systems involved have suffered from a variety of problems, from

poor voice recognition to complex ecosystems.

Five years ago industry leading voice recognition was only at around 75% accuracy;

recent advances in machine learning techniques, systems and hardware

have increased the rate of the best systems to around 95–97%.

Approaching

and crossing this cognitive threshold has been the single biggest

factor in the current boom. Humans recognise spoken words with around

95% accuracy, and use context to error correct. Any automated system

with a lower recognition accuracy feels frustrating to most users and

isn’t therefore commercially viable.

Related

developments in machine learning approaches to intent derivation

(explained later in this article) are also a huge contributing factor.

Commercial systems for this functionality crossed a similar threshold a

couple of years ago and were responsible for the boom in bots; voice is

really just bots without text.

Bots

themselves have also been around for decades, but the ability to

process natural language rather than simply recognising keywords has led

to dialogue-based interactions, which in turn powered the recent

explosion in platforms and services.

Assistants

Pre-eminent

in the current voice technology landscape is the rise of virtual

automated assistants. Although Siri (and other less well known

alternatives) have been available for years, the rise of Alexa and

Google Assistant in particular heralds a wider platform approach.

The

new assistants promote whole ecosystems and function across a range of

devices; Alexa can control your lights, tell you what your meetings are

for the day, and help you cook a recipe. These provide opportunities for

brands and new entrants alike to participate in the voice experience.

Effect on markets

A

new, widely used mechanism for online commerce is always going to be

hugely disruptive, and it’s currently too early to know in detail what

all the effects of voice will be for brands.

Three

of the biggest factors to take into account are firstly that many

interactions will take place entirely on platform, reducing or removing

the opportunity for search marketing. Secondly the fact that

dialogue-based interactions don’t support lists of items well means that

assistants will generally try to recommend a single item rather than

present options to the user, and lastly that the entire purchase process

will, in many cases, take place with no visual stimulus whatever.

All

of these factors are currently receiving a lot of attention but it’s

safe to say that the effect on (especially FMCG) brands is going to be

enormous, especially when combined with other factors like Amazon’s

current online dominance as both marketplace and own-brand provider.

Two strategies that are currently being discussed

as possible ways to approach these new challenges are either to market

to the platforms (as in, try to ensure that Amazon, Google etc.

recommend your product to users), and/or to try to drastically increase

brand recognition so that users ask for your product by name rather than

the product category. Examples would be the way the British use

‘Hoover’ interchangeably with ‘vacuum cleaner’ or Americans using

‘Xerox’ meaning ‘to photocopy’.

Role vs other touchpoints

Over

the next few years many brands will create a presence on voice

platforms. This could take any form, from services providing utilities

or reducing the burden on customer services, to communications and

campaign entertainment.

Due

to the conversational nature of voice interfaces, the lack of a

guaranteed visual aspect and the role of context in sensitive

communications, few or no brands will rely on voice alone; it won’t

replace social, TV, print and online but rather complement these

platforms.

It’s

also worth noting that a small but significant part of any brand’s

audience won’t be able to speak or hear; for them voice only interfaces

are not accessible (although platforms such as Google Assistant also

have visual interfaces).

Branding and voice

In

theory voice technology gives brands an unprecedented opportunity to

connect with consumers in a personal, even intimate way; of all the

potential brand touchpoints, none have the potential for deep personal

connection at scale that voice does.

At

the same time, the existing assistant platforms all pose serious

questions for brands looking to achieve an emotional connection to some

extent. Google Assistant provides the richest platform opportunity for

brands, but is still at one remove from ‘native’ functionality, while

Alexa imposes extra limitations on brands.

Having

said that, voice technology does represent an entirely new channel with

some compelling brand characteristics, and despite the drawbacks may

represent an important opportunity to increase brand recognition.

Human-like characteristics

It

is well established that people assign human characteristics to all

their interactions, but this phenomenon is especially powerful with

spoken conversations. People develop feelings for voice agents; over a third of regular users wish their assistant were human and 1 in 4 have fantasised about their assistant.

Voice-based

services, for the first time, allow brands to entirely construct the

characteristics of the entity that represents them. The process is both

similar to and more in depth than choosing a brand spokesperson; it’s

important to think about all the various aspects of the voice that

represents the brand or service.

Examples

of factors worth considering when designing a voice interface include

the gender, ethnicity and age of the (virtual) speaker, as well as their

accent. It may be possible to have multiple different voices, but that

raises the question of how to choose which to use — perhaps by service

offered or (if known) by customer origin or some other data points.

Another

interesting factor is the virtual persona’s relationship to both the

user and the brand; is the agent like a host? An advisor? Perhaps a

family member? Does it represent the brand itself? Or does it talk about

the brand in the third person? Does it say things like “I’ll just check

that for you”, implying access to the brand’s core services that’s

distinct from the agent itself?

There

are of course technical considerations to take into account; depending

on the service you create and the platform it lives on it may not be

possible to create a bespoke voice at all, or there may be limits on the

customisation possible. This is explored in more detail below.

In

some cases, it may even be possible to explore factors that are richer

still; such as the timbre of the voice and ‘soft’ aspects like the

warmth that the speech is delivered with.

Lastly,

it’s worth noting that voice bots have two way conversations with

individual users that are entirely brand mediated; there is no human in

the conversation who may be having a bad day or be feeling tired.

Tone of Voice in bot conversations

Tone

of Voice documents and editorial guides are generally written to

support broadcast media; even as they have become more detailed to

inform social media posting, guides often focus on crafted headline

messages.

Conversational interfaces push the bounds of those documents further than ever before, for a few reasons.

Firstly,

voice agents will typically play a role that is closer to the pure

brand world than either sales or support; entertainment and other

marketing activities make the role of an agent often closer to a social

media presence than a real human, but with a human-like conversational

touchpoint.

Secondly,

both bots and voice agents have two way conversations with customers.

In a sense this is no different than sales or customer service (human)

agents, but psychologically speaking those conversations are with a

human first and a brand representative second.

In

a conversation with a customer services representative, for example,

any perceptions the consumer has about the brand are to some extent

separate from the perceptions about the human they are interacting with.

Lastly,

it’s critical to note that users will feel empowered to test the

boundaries of an automated agent’s conversation more than they would a

human, and will naturally test and experiment.

Expect

users to ask searching questions about the brand’s competitors or the

latest less-than-ideal press coverage. If users are comfortable with the

agent, expect them to ask questions unrelated to your service, or even

to talk about their feelings and wishes. Even in the normal course of

events, voice interactions will yield some unusual and new situations

for brands. For example, this commenter on a New York Times article was interrupted mid sentence, causing a brief stir and a lot of amusement.

How

voice agents deal with the wide range of new input comes down not only

to the information the agent can respond to, but more importantly the

way in which it responds. To some extent this is the realm of UX

writing, but hugely important in this is the brand voice.

As

an example, if you ask Google Assitant what it thinks of Siri (many

users’ first question), it might reply “You know Siri too?! What a small

world — hope they’re doing well”.

Service design for voice

Whether

based in utility, entertainment, or something else, some core

considerations come into play when building a voice-based service. It’s

not uncommon for these factors to lead to entirely new services being

built for brands.

Obviously

it’s important to consider the impact that not having a screen will

have on the experience. As an example, lists of results are notoriously

bad over a voice interface; as an experiment read the first page of a

Google search results out loud. This means that experiences tend to be

more “guided” and rely less on the user to select an option — although

there are also lots of other implications.

With

that in mind, it’s also good to note that increasingly voice platform

users may have screens that both they and the assistant can access;

either built into the device (like with Echo Show) or via smartphone or

ecosystem-wide screens such as with the Google Assistant. While these

screens can’t be counted upon, they can be used to enrich experiences

where available.

Another

important factor is the conversational nature of the interface; this

has a huge impact on the detail of the service design but can also mean

selecting services with a high ratio of content to choices, or at least

where a linear journey through the decision matrix would make sense.

Interfaces of this sort are often hugely advantageous for complex

processes where screen-based interfaces tend to get cluttered and

confusing.

Finally,

as with social, context is massively important to the way users access a

voice service. If they are using a phone they may be in public or at

home, they may be rushed or relaxed, and all these affect the service.

If the user is accessing the service via a smart speaker they are likely

at home but there may be other people present; again affecting the

detail of the service.

In

general, services well suited to voice will often be limited in scope

and be able to reward users with very little interaction; more complex

existing services will often need AI tools to further simplify their

access before being suitable to voice.

The voice landscape

In

the last two to three years the landscape of voice technology has

shifted dramatically as underlying technologies have reached important

thresholds. From Google and Amazon to IBM and Samsung, many large

technology companies seem to have an offering in the voice area, but the

services each offers differ wildly.

Devices and Contexts

It’s

important to note that many devices do have capabilities beyond voice

alone. Smart speakers generally are only voice, but also have lights

that indicate to users when they are listening and responding, and so

help to direct the conversation.

Newer

Alexa devices like the Echo Show and Echo Spot are now shipping with

screens and cameras built in, while Google Assistant is most commonly

used on smartphones where a screen mirrors the conversation using text,

by default. On smartphones and some other devices users have the option

to have the entire dialogue via text instead of voice, which can make a

difference to the type of input they receive as well as the nuances

available in the output.

Screen

based conversational interfaces are developing rapidly to also include

interactive modules such as lists, slideshows, buttons and payment

interfaces. Soon voice controlled assistants will also be able to use

nearby connected TVs to supplement conversational interfaces, although

what’s appropriate to show here will differ from smartphone interfaces.

As

should be clear, as well as a wide range of available capabilities, the

other major factor affecting voice interactions is context; users may

be on an individual personal device or in a shared communal space like a

kitchen or office; this affects how they will be comfortable

interacting.

Platforms and ecosystems

Amazon Alexa

Perhaps

the most prominent UK/US based voice service is Amazon’s Alexa:

initially accessible via Echo devices but increasingly available in

hardware both from Amazon and third parties.

Amazon has a considerable first mover advantage in the market (72% smart speaker market share),

and it’s arguably the commercial success of the range of Echo devices

that has kick-started the recent surge in offerings from other

companies.

Alexa

is a consumer facing platform that allows brands to create ‘skills’

that consumers can install. End users configure Alexa via a companion

app; among other things this allows them to install third party ‘skills’

from an app store. An installed skill allows the end user to ask Alexa

specific extra questions that expose the skill’s service offering; e.g.

“Alexa, what’s my bank balance?”

There are now approximately 20,000 Alexa skills across all markets, up from 6,000 at the end of 2016. Although many have extremely low usage rates at present, Amazon has recently introduced funding models to continue to motivate third party developers to join its ecosystem.

With an estimated 32M Alexa-powered devices sold by the end of 2017

(of which around 20M in Q4) there’s no doubt that the platform has a

lot of reach, but Alexa’s skills model and Amazon’s overall marketplace

strategy combine to place brands very much in Amazon’s control.

Google Assistant

Google

launched the Home device, powered by the Google Assistant in May 2016,

over a year after Amazon launched the Echo. Google has been aggressively

marketing the Assistant (and Home hardware devices) both to consumers

and to partners and brands. Google already commands a market share (of smart speakers) of 15%, double that of the previous year; their market share of smartphone voice assistants is 46%, projected to rise to 60% by 2022.

Google’s

Assistant is also being updated with new features at an incredible

rate, and arguably has now taken the lead in terms of functionality

provided to users and third party developers.

Perhaps

most interestingly, Assistant takes an interesting and different

approach to brand integration compared to other offerings, with the

Actions on Google platform. Using this platform, brands are able to

develop not only the service offering but the entire conversational

interface, including the voice output of their service.

Users

don’t need to install third party apps but can simply ask to speak to

them; much the way someone might ask a switchboard or receptionist to

speak to a particular person. Once speaking to a particular app, users

can authenticate, allow notifications, switch devices and pay, all

through the Assistant’s conversation based voice interface.

By

integrating Assistant tightly with Android, the potential reach of the

platform is enormous; there are currently 2.5Bn Android devices in

operation. The software is also available to third party hardware

manufacturers, further increasing the potential of the ecosystem.

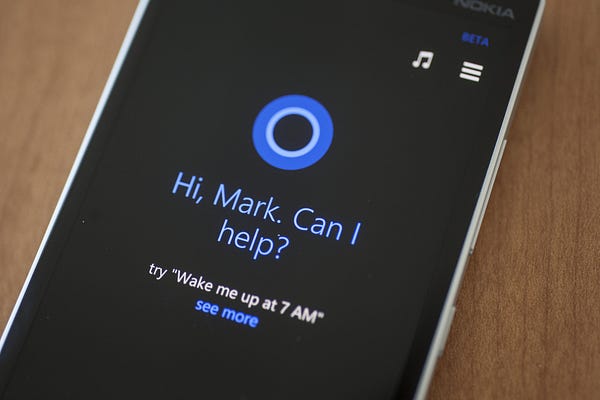

Microsoft Cortana

Microsoft’s Cortana is installed on every Windows 10 device and has an impressive 145M monthly active users (probably mostly via XBox), but is currently less heavily promoted and updated than the offerings from Google and Amazon.

Cortana

provides a similar ‘skill’ interface to Alexa, but has started

developing this relatively late and is playing catch-up both in terms of

core functionality and the number of available integrations.

Microsoft’s

huge overall user base and its dominance in both work-related software

and gaming ecosystems do give Cortana a powerful (and growing) presence

in the market, despite its share of dedicated smart speaker devices

being small.

Baidu

Baidu

(often called the ‘Chinese Google’) arguably started the recent trend

for voice interfaces with a combination of groundbreaking technology and

a huge installed user base with various cultural and socioeconomic

predispositions to favouring voice over text.

Baidu

recently released DuerOS, a platform for third party hardware

developers to build their own voice powered devices, and via the ‘Baidu

Brain’ offers a suite of AI platforms for various purposes (many

involving voice).

Most

consumers currently interact with Baidu’s voice technologies via their

Chinese language dedicated services (i.e. without any third party

integrations).

Siri, Bixby and Watson

Apple’s

Siri and Samsung’s Bixby are both voice assistants that currently only

work on a given device or perhaps in the manufacturer’s ecosystem;

neither could be called a platform as they don’t offer third parties

access to create services.

Both

have reasonable market share due to the number of phones they appear

on, but their gated offerings and lower accuracy voice recognition now

make them seem limited by comparison with other assistants.

IBM’s Watson is perhaps most usefully seen as a suite of tools that brands can use to create bespoke services.

Content and services

There

are a lot of considerations when designing services for voice based

conversational interfaces; these are touched on above but affect the

range of functionality that is available.

— Utility

The

vast majority of voice services currently available are utilities,

giving access to a simple piece of functionality already available via

other methods. These range from the more mundane (playing a specific

radio station or listening to news) to the more futuristic (adjusting

the lights or playing a specific film on the TV), via provider-specific

functions like ordering a pizza or a taxi.

Lots

of brands are beginning to offer services in this area, from home

automation or similar niche organisations like WeMo and Plex or Philips

Hue, to more widely used services like Uber and Dominos, but

interestingly also including big brands offering innovative services.

Both Mercedes and Hyundai, for example, allow users to start their cars

and prewarm them from various voice assistant platforms.

— Entertainment

Various

games, jokes and sound libraries are available on all the major

platforms from a variety of providers, often either the platform

provider themselves (i.e. Google or Amazon) or small companies or

individual developers.

A

few brands are starting to experiment more with the possibilities of

the platform however; for example Netflix and Google released a companion experience for Season 2 of Stranger Things, and the BBC recently created a piece of interactive fiction for the Alexa.

The potential for entertainment pieces in this area is largely untapped; it is only just beginning to be explored.

Tools

Many

sets of tools exist for building voice services, as well as related

(usually AI based) functionality. By and large the cloud based services

on offer are free or cheap, and easy to use. Serious projects may

require bespoke solutions developed in house but that is unnecessary for

the majority of requirements.

A full rundown of all the tools available is outside the scope of this article, but notable sets are IBM’s Watson Services, Google’s Speech API and DialogFlow, and Microsoft’s Cognitive Services.

All

these mean that prototyping and experimentation can be done quickly and

cheaply and production-ready applications can be costed on a usage

model, which is very cost effective at small scale.

— Speech Generation

Of

particular note to brands are the options around speech generation, as

these are literally the part of the brand that end users interact with.

If

the service being offered has a static, finite set out possible

responses to all user input, it is possible to use recorded speech. This

approach can be extended in some cases with a

record-and-stitch-together approach such as used by TfL.

For

services with a wide range of outputs, generated voices are the only

practical way to go, but even here there are multiple options. There are

multiple free, more-or-less “computer”-sounding voices easily

available, but we would recommend exploring approaches using voice

actors to create satnav-like TTS system.

The

rapidly advancing field of Machine Learning powered generated speech

that can sound very real and even like specific people is worth keeping

an eye on; this is not yet generally available but Google is already using Wavenet for Assistant in the US while Adobe was working on a similar project.

The technology behind voice

What people refer to as voice is really a set of different technologies all working together.

Notably, Speech To Text

is the ‘voice recognition’ component that processes some audio and

outputs written text. This field has improved in leaps and bounds in

recent years, to the point where some systems are now better at this

than humans, across a range of conditions.

In June, Google’s system was reported to have 95% accuracy

(the same as humans, and an improvement of 20% over 4 years), while

Baidu is usually rated as having the most accurate system of all with

over 97%.

The core of each specific service lies in Intent Derivation,

the set of technologies based on working out what a piece of text

implies the underlying user intent is — this matches user requests with

responses the service is able to provide.

The

recent rise in the number (and hype) of bots and bot platforms is

related to this technology, and as almost all voice systems are really

just bots with voice recognition added in, this technology is crucial.

There are many platforms that provide this functionality (notably IBM Watson, and the free DialogFlow, among many others).

The other important set of voice-related technologies revolve around Speech Generation.

There are many ways to achieve this and the options are very closely

related to the functionality of the specific voice service.

The

tools and options relating to this are explored earlier in this

article, but they range widely in cost and quality, based on the scope

of the service and the type of output that can be given to users.

Considerations

Creating a voice-first service involves additional considerations as compared to other digital services.

First

and foremost, user privacy is getting increased attention as audio

recordings of users are sent to the platform and/or brand and often

stored there. Depending on the manner in which the service is available

to users this may be an issue just for the platform involved, or may be

something the brand needs to address directly.

Recently the C4 show ‘Celebrity Hunted’ caused a bit of a backlash against Alexa

as users saw first hand the power of the stored recordings being

available in the future. There are also worries about the ‘always on’

potential of the recording, despite major platforms repeatedly trying to

assure users that only phrases starting with the keyword get recorded

and sent to the cloud.

As

with most things however, a reasonable value exchange is the safest way

to proceed. Essentially, ensure that the offering is useful or

entertaining.

Another

consideration, as touched upon earlier in this article, is that the

right service for a voice-first interface may not be something your

brand already offers — or at the least that the service may need

adaptation to be completely right for the format. We’ve found during

workshops that the most interesting use cases for branded voice services

often require branching out into whole new areas.

Perhaps

most interestingly, this area allows for a whole new interesting set of

data to be collected about users of the service — actual audio

recordings aside, novel services being used in new contexts (at home

without a device in hand, multiuser, etc) should lead to interesting new

insights.

Recommendations for brands

We

believe that long term, many brands will benefit from having some or

all of their core digital services available over voice interfaces, and

that the recent proliferation of the technology has created

opportunities in the short and medium terms as well.

A good starting point is to start to include voice platforms in the mix for any long term planning involving digital services.

Ideally

brands should start to work on an overall voice (or agent, including

bots) strategy for the long term. This would encompass which services

might best be offered in these different media, and how they may

interact with customer services, CRM, social and advertising functions

as well as a roadmap to measure progress against.

In

the short term, we believe brands ought to experiment using

off-the-shelf tools to rapidly prototype and even to create short-lived

productions, perhaps related to campaigns.

The

key area to focus on for these experiments should be how the overall

brand style, tone of voice, and customer service scripts convert into a

voice persona, and how users respond to variations in this persona.

This

experimentation can be combined with lightweight voice-first service

design in service of campaigns, but used to build an overall set of

guides and learnings that can be used for future core brand services.