Facebook’s newsfeed changes: a disaster or an opportunity for news publishers?

Social

media and digital executives in newsrooms already have a tough job

connecting their content to consumers via social media, but Facebook’s proposed changes in the algorithms of its ‘newsfeed’

are going to make it a lot harder. Social networks offer immense

opportunities for reaching vast new audiences and increasing the

engagement of users with journalism. The most important platform in the

world is about to make that more difficult.

Clearly,

this is a blow for news publishers who have spent the last decade or so

fighting a battle for survival in a world where people’s attention and

advertising have shifted to other forms of content and away from news

media brand’s own sites. They are clearly very concerned. Yet, could this be a wake-up call that will mean the better, most adaptive news brands benefit?

I’m

not going to argue that this is good news for news publishers, but

blind panic or cynical abuse of Facebook is not a sufficient response.

The honest answer is that we don’t know exactly what the effect will be

because Facebook, as usual, have not given out the detail and different

newsrooms will be impacted differently.

It’s exactly the kind of issue we are looking at in our LSE Truth, Trust and Technology Commission.

Our first consultation workshop with journalists, and related

practitioners from sectors such as the platforms, is coming up in a few

weeks. This issue matters not just for the news business. It is also

central to the quality and accessibility of vital topical information

for the public.

Here’s my first attempt to unpack some of the issues.

Firstly,

this is not about us (journalists). Get real. Facebook is an

advertising revenue generation machine. It is a public company that has a

duty to maximise profits for its shareholders. It seeks people’s

attention so that it can sell it to advertisers. It has a sideline in

charging people to put their content on its platform, too. It is a

social network, not a news-stand. It was set up to connect ‘friends’ not

to inform people about current affairs. Journalism, even where shared

on Facebook, is a relatively small part of its traffic.

Clearly,

as Facebook has grown it has become a vital part of the global (and

local) information infrastructure. Other digital intermediaries such as

Google are vastly important, and other networks such as Twitter are

significant. And never forget that there are some big places such as

China where other similar networks dominate, not Facebook or other

western companies. But in many countries and for many demographics,

Facebook is the Internet, and the web is increasingly where people get their journalism. It’s a mixed and shifting picture but as the Reuters Digital News Report shows, Facebook is a critical source for news.

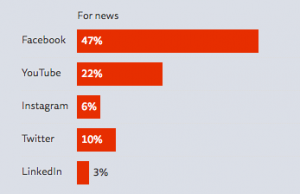

From Reuters Digital News Report 2017

If you read Zuckerberg’s statement he makes it clear that he is trying to make Facebook a more comfortable place to be:

“recently we’ve gotten feedback from our community that public content — posts from businesses, brands and media — is crowding out the personal moments that lead us to connect more with each other.”

His users are ‘telling him’ (i.e. fewer of them are spending less time on FB) what a plethora of recent studies and books

have shown which is that using Facebook can make you miserable. News

content — which is usually ‘bad’ news — doesn’t cheer people up. The

angry, aggressive and divisive comment that often accompanies news

content doesn’t help with the good vibes. And while the viral spread of

so-called ‘fake news’ proves it is popular, it also contributes to the

sense that Facebook is a place where you can’t trust the news content.

Even when it is credible, it’s often designed to alarm and disturb. Not

nice. And Facebook wants nice.

One response to this from journalists is despair and cynicism. The UK media analyst Adam Tinworth sums this approach up in a witty and pithy ‘translation’ of Zuckerberg’s statement:

“We can’t make money unless you keep telling us things about yourself that we can sell to advertisers. Please stop talking about news.”

Another

accusation is that Facebook is making these changes because of the

increasing costs it is expending at the behest of governments who are

now demanding it does more to fight misinformation and offensive

content. That might be a side-benefit for Facebook but I don’t think

it’s a key factor. It might even be a good thing for credible news if

the algorithmic changes include ways of promoting reliable content. But

overall the big picture is that journalism is being de-prioritised in

favour of fluffier stuff.

Even Jeff Jarvis, the US pioneer of digital journalism who has always sought to work with the grain of the platforms, admits that this is disturbing:

“I’m worried that news and media companies — convinced by Facebook (and in some cases by me) to put their content on Facebook or to pivot to video — will now see their fears about having the rug pulled out from under them realized and they will shrink back from taking journalism to the people where they are having their conversations because there is no money to be made there.”*

The

Facebook changes are going to be particularly tough on news

organisations that invested heavily in the ‘pivot to video’. These are

often the ‘digital native’ news brands who don’t have the spread of

outlets for their content that ‘legacy’ news organisations enjoy. The

BBC has broadcast. The Financial Times has a newspaper. These

organisations have gone ‘digital first’ but like the Economist they have

a range of social media strategies. And many of them, like the New York

Times, have built a subscription base. Email newsletters provide an

increasingly effective by-pass for journalism to avoid the social media

honey-trap. It all makes them less dependent on ‘organic’ reach through

Facebook.

But

Facebook will remain a major destination for news organisations to

reach people. News media still needs to be part of that. As the

ever-optimistic Jarvis also points out,

if these changes mean that Facebook becomes a more civil place where

people are more engaged, then journalism designed to fit in with that

culture might thrive more:

“journalism and news clearly do have a place on Facebook. Many people learn what’s going on in the world in their conversations there and on the other social platforms. So we need to look how to create conversational news. The platforms need to help us make money that way. It’s good for everybody, especially for citizens.”

News

organisations need to do more — not just because of Facebook but also

on other platforms. People are increasingly turning to closed networks

or channels such as Whatsapp. Again, it’s tough, but journalism needs to

find new ways to be on those. I’ve written huge amounts

over the last ten years urging news organisations to be more networked

and to take advantage of the extraordinary connective, communicative

power of platforms such as Facebook. There has been brilliant

innovations by newsrooms over that period to go online, to be social and

to design content to be discovered and shared through the new networks.

But this latest change shows how the media environment continues to

change in radical ways and so the journalism must also be reinvented.

Social media journalist Esra Dogramaci has written an excellent article

on some of the detailed tactics that newsrooms can use to connect their

content to users in the face of technological developments like

Facebook’s algorithmic change:

“if you focus on building a relationship with your audience and developing loyalty, it doesn’t matter what the algorithm does. Your audience will seek you out, and return to you over and over again. That’s how you ‘beat’ Facebook.”

Journalism Must Change

The

journalism must itself change. For example, it is clear that emotion is

going to be an even bigger driver of attention on Facebook after these

changes. The best journalism will continue to be factual and objective

at its core — even when it is campaigning or personal. But as I have written before,

a new kind of subjectivity can not only reach the hearts and minds of

people on places like Facebook, but it can also build trust and

understanding.

This

latest change by Facebook is dramatic, but it is a response to what

people ‘like’. There is a massive appetite for news — and not just

because of Trump or Brexit. Demand for debate and information has never

been greater or more important in people’s everyday lives. But we have

to change the nature of journalism not just the distribution and

discovery methods.

The media landscape is shifting to match people’s real media lives in our digital age. Another less noticed announcement from Facebook

last week suggested they want to create an ecosystem for local

personalised ‘news’. Facebook will use machine learning to surface news

publisher content at a local level. It’s not clear how they will vet

those publishers but clearly this is another opportunity for newsrooms

to engage. Again, dependency on Facebook is problematic, to put it

mildly, but ignoring this development is to ignore reality. The old

model of a local newspaper for a local area doesn’t effectively match

how citizens want their local news anymore.

What Facebook Must Do

Facebook

has to pay attention to the needs of journalism and as it changes its

algorithm to reduce the amount of ‘public content’ it has to work harder

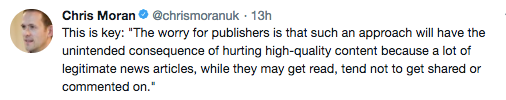

at prioritising quality news content. As the Guardian’s outstanding

digital executive Chris Moran points out, there’s no indication from

Facebook that they have factored this into the latest change:

Fighting

‘fake news’ is not just about blocking the bad stuff, it is ultimately

best achieved by supporting the good content. How you do that is not a

judgement Facebook can be expected or relied upon to do by itself. It

needs to be much more transparent and collaborative with the news

industry as it rolls out these changes in its products.

When

something like Facebook gets this important to society, like any other

public utility, it becomes in the public interest to make policy to

maximise social benefits. This is why governments around the world are

considering and even enacting legislation or regulation regarding the

platforms, like Facebook. Much of this is focused on specific issues

such as the spread of extremist or false and disruptive information.