The big secret about “tech people”, fixing things and how to control your technology

Hint: it’s neither hard nor dangerous

In

this article, I’d like to talk about the “divide in technology” and how

you can become proficient at solving tech problems even if you have

never done it before.

The Gap

There

is a fundamental divide in how people deal with tech problems. It seems

that some people see computers, smartphones and other technical devices

as “black boxes”, most of the time doing what they want, but at times

showing frustrating errors or just plainly stopping to work.

Others

(with a winking eye referred to as “tech people”) see those devices as a

system of parts: hardware, software and things that run on the

internet. While errors and failures are certainly annoying, they are

merely symptoms that some part of the system is malfunctioning. And since it’s technology, the various components can be fixed.

The

difference between those groups is that the first group is intimidated

by technology — you might hear someone say “Oh, he (the computer)

doesn’t like me”, as if it’s a personal thing and the technological

system can be blamed. The other group doesn’t put the blame on the

system as a whole, vicious entity, but instead treat it as it is: a

collection of parts.

It’s

no shame to belong to group one, after all, technological education and

systems thinking is rarely taught and if you never had someone else

introduce you to the topic, you were likely never exposed to the ideas

behind it. However, I encourage you to read on and discover it’s quite

easy to understand and to switch over to the “tech” side in no time.

Why

should you do this? Because it gives you power and control over the

things you own. You are absolutely capable of fixing and repairing both

software and hardware problems, once you understand the basics. And each

time you succeed in fixing something, you will gain confidence and

experience. Plus, it’s actually pretty fun.

Everything is just a collection of parts

As

mentioned in the intro, every piece of technology is a quite elaborate

collection of parts, divided into hardware and software. The hardware is

the actual thing that you carry around, most of the times small boards

or chips that fulfill a certain function.

Two good things: those components are similar on almost all systems (I’m talking about computers, tablets and smartphones).

They

all have a processor unit (doing the computations), a permanent storage

(where all your photos are for instance) and a temporary storage

(supplying the files that are in use right at the moment to the

processor).

Those

three are absolutely necessary for the basic functions. Then, of

course, you have things that support everything else: batteries,

screens, sensors, input devices (keyboards, trackpads), wireless chips

and a series of boards connecting everything together.

The

second good thing is that you don’t need to understand how each of

those components work (or even how the system works at all) and you can

still fix the system as a whole.

On

top of this, there is software: an operating system and applications

running on this system. Again, you don’t need to understand how this all

works, just be aware of its existence.

Have you tried turning it off and on again?

It

seems like a tired old joke, but it’s quite true. More than half of all

errors on almost all systems can be “fixed” by turning off the system

and restarting it.

This allows the system to begin with a blank slate, it reloads the software and starts all calculations afresh.

It

is truly the one thing that a “tech person” will do first when trying

to fix a problem. Switch everything off (completely, ideally also

disconnect the power), then back on. You will be surprised how many

errors are never showing up again! This technique can be adapted to

resetting and reinstalling software, but we’ll get into that in a later

article.

Turn it off. Turn it back on. Fix most of your errors.

You can’t really break something

I find that most of the time, people are not trying to fix things because they are afraid to damage those things permanently.

Another

good thing (this article is full of positivity): you can’t really break

something as long as you don’t physically break part of the system.

Keeping your technology dry and reasonably clean is a good way to start.

It’s

also quite unlikely that you damage your software beyond repair. Rest

assured that there is almost always a way to completely reset

everything. Which brings us to the next point and then we will go into

the details.

Store your files securely

As

mentioned above, your files are stored on the permanent storage (hard

drive) of your device. Luckily, in the last decade it has gotten

incredibly easy to also store all your files in the “cloud”, meaning a

separate computer somewhere on the internet, owned by a company.

The

most famous of these services, like Dropbox, iCloud, GoogleDrive and

OneDrive are reliable and widely used, while alternative might be suited

to special needs.

I

won’t go into any detail on how to choose the best service, you should

be fine with typing “best cloud storage providers 2018” into Google.

The

point is: while I said you can’t break anything on your system, you

might lose your files, programs, settings and achievements if you don’t

save them on another device first.

Use

a cloud storage, external hard drive or another computer to move

important documents out of your system for the time of the repairs.

Things change, for better or for worse, it’s never just you

You

know the saying: never change a running system. Many software

developers don’t seem to heed this, they are constantly updating,

improving, iterating and changing.

Most

of these changes are benign, while sometimes they break the very thing

that you rely on for your work. It is annoying, it costs energy and

time.

Yet, we all have to accept it, sort of the price we pay for getting accelerated technological progress.

And

despite the myriads of different technological configurations,

operating systems, smartphones and programs there are, there is a high

chance that someone, somewhere has already had the same problem and

found a solution and shared it with the world.

Which brings us to…

The big secret

This is the big one. The secret you have been waiting for. How do “tech people” actually fix things?

The answer, of course, is a simple process.

They google the error and then follow whatever other people have tried.

Yes,

that’s all. That is how most of the errors get solved and how most

things get repaired and in fact, how most things are learned.

You

just google what you are trying to do and then spend some time going

through the answers. It might not be the first answer that helps you,

but chances are that somewhere in the first five answers, something

will.

The

art is within the right phrasing of the question. I’ll walk you through

an example: recently, my 3D software “Blender” started to display black

boxes instead of the usual interface. It was mildly annoying, so I

tried to fix it.

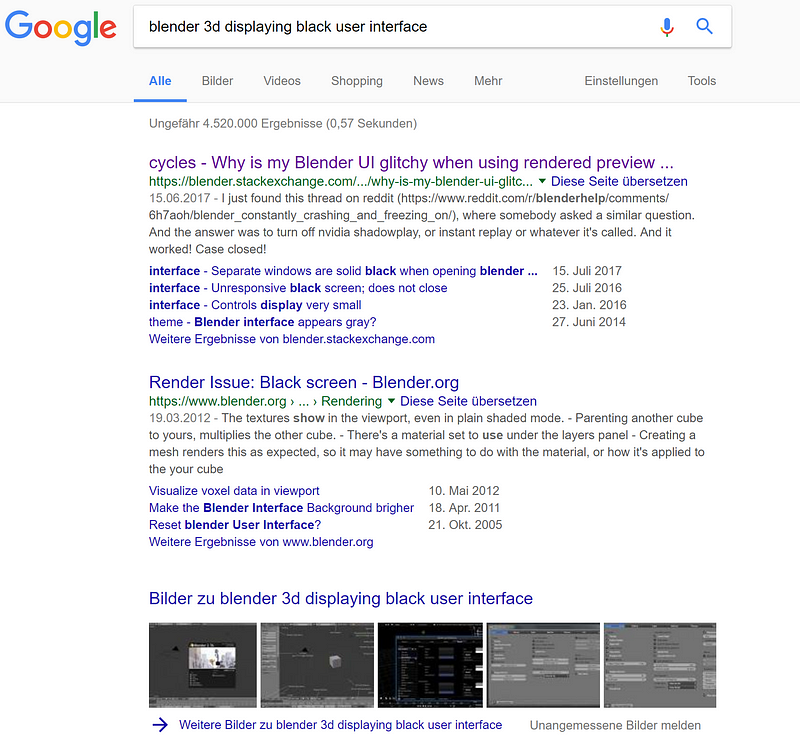

Here

is how you construct the google query: type the program name first,

then add a short and succinct description of what’s wrong. For instance:

“blender 3d displaying black user interface”. Here is what Google gives

me:

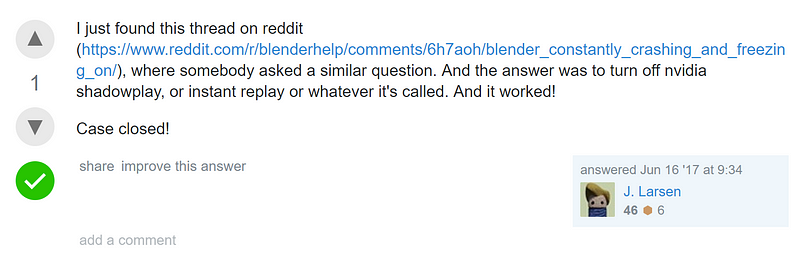

And

I simply go to the first answer, which is a site called

stackexchange.com. It is a platform/ community where lots of tech

questions are answered and it is quite trustworthy. Reading the question

that someone else asked, I think that they have the same issue. And

behold, below there is an answer.

I know that shadowplay is a program for my graphics card, so I turned it off.

It fixed the issue, no more black boxes.

If

I didn’t know how to turn it off, guess what: I’d google it (“turning

off nvidia shadowplay”). There are tutorials for everything online.

This principle works with any error message, too.

Just

don’t click it away angrily, look at it, read it and if you don’t

understand it, copy the exact words into Google, combined with the

software from which it came, for instance “windows 10 error 0x80200056”.

It looks like gibberish and I have no clue what it means, but other

people do!

Put it into Google, read the first answer (like seriously, read it like a really good recipe) and follow it.

Remember, you are quite unlikely to break anything, so just follow the steps.

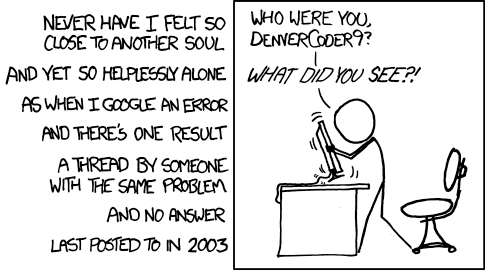

And then there is this case:

Yes,

there is a chance that your problem is absolutely rare and unique. It

happens to all of us. We live with it. We reinstall the whole system. We

buy a new computer. But we can always say that we tried.

I’ll probably go into a little more depth on this next week, but for now, you have a basic understanding of your tech!

The more you fix and try and change, the more confident you will become.

Soon, you will be one of the “tech people”.