There

are a lot of scary things happening these days, but here’s what keeps

me up late at night. A handful of corporations are turning our open

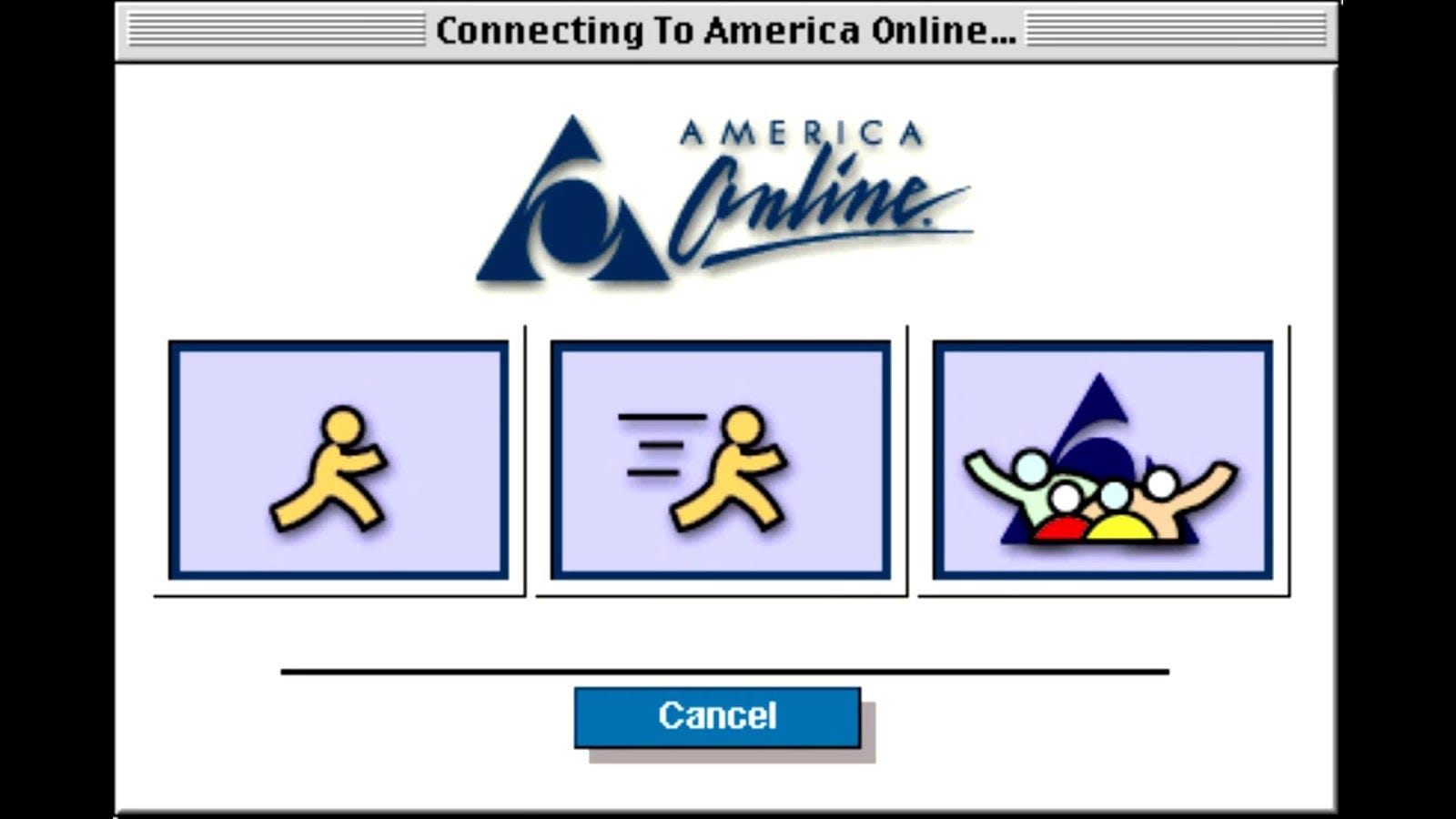

internet into this:

These

corporations want to lock down the internet and give us access to

nothing more than a few walled gardens. They want to burn down the

Library of Alexandria and replace it with a magazine rack.

Why? Because they’ll make more money that way.

This may sound like a conspiracy theory, but this process is moving forward at an alarming rate.

History is repeating itself.

So

far, the story of the internet has followed the same tragic narrative

that’s befallen other information technologies over the past 160 years:

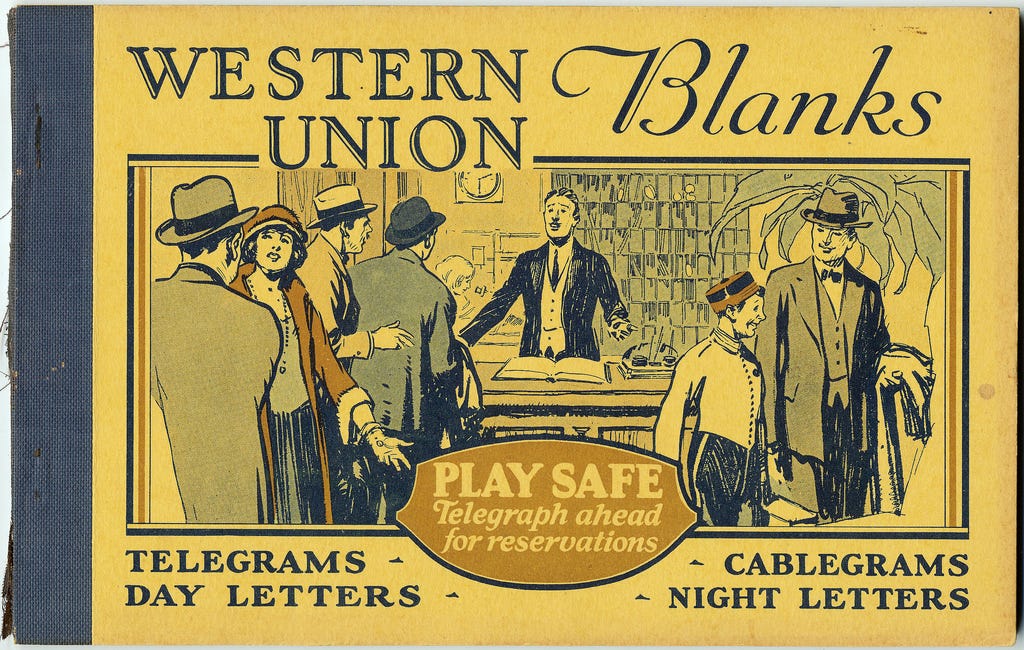

- the telegram

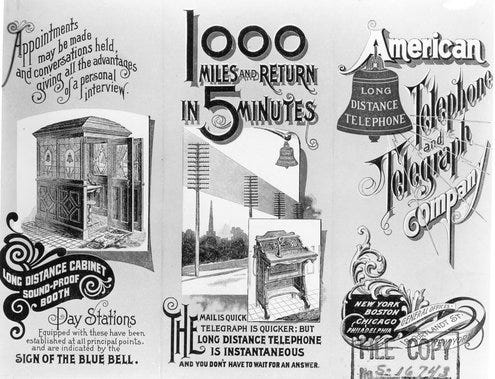

- the telephone

- cinema

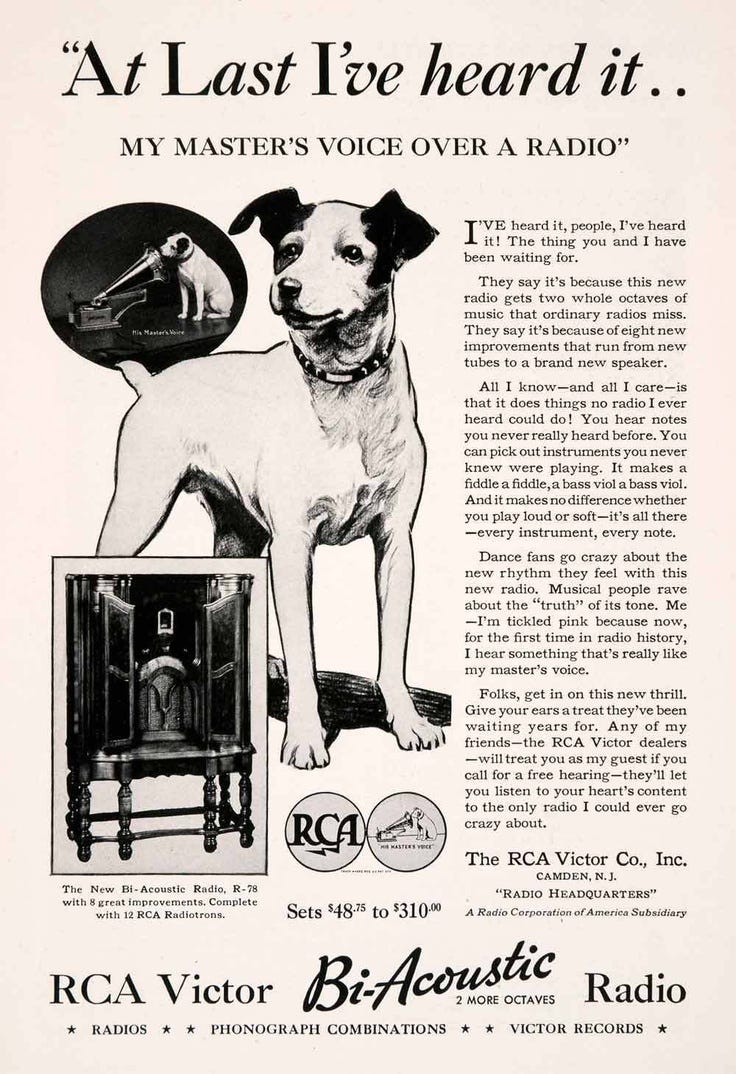

- radio

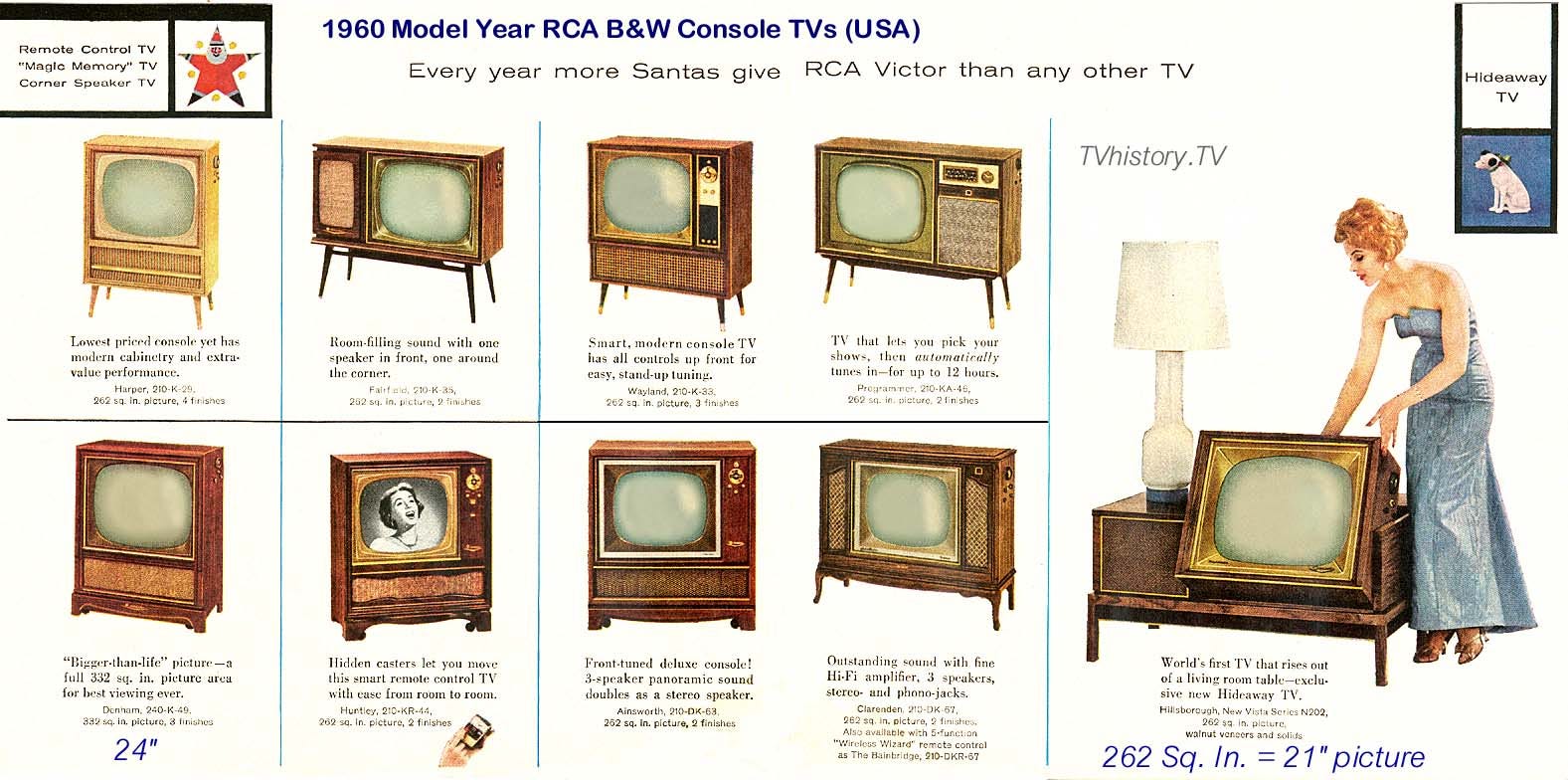

- television

Each of these had roughly the same story arc:

- Inventors discovered the technology.

- Hobbyists pioneered the applications of that technology, and popularized it.

- Corporations took notice. They commercialized the technology, refined it, and scaled it.

- Once the corporations were powerful enough, they tricked the government into helping them lock the technology down. They installed themselves as “natural monopolies.”

- After a long period of stagnation, a new technology emerged to disrupt the old one. Sometimes this would dislodge the old monopoly. But sometimes it would only further solidify them.

This

loop has repeated itself so many times that Tim Wu — the Harvard law

professor who coined the term “Net Neutrality” — has a name for it: The Cycle.

“History shows a typical progression of information technologies, from somebody’s hobby to somebody’s industry; from jury-rigged contraption to slick production marvel; from a freely accessible channel to one strictly controlled by a single corporation or cartel — from open to closed system.” — Tim Wu

And right now, we’re in step 4 the open internet’s narrative. We’re surrounded by monopolies.

The

problem is that we’ve been in step 4 for decades now. And there’s no

step 5 in sight. The creative destruction that the Economist Joseph

Schumpeter first observed in the early 1900s has yet to materialize.

The

internet, it seems, is special. It’s the ultimate information

technology — capable of supplanting the telegram, telephone, radio,

cinema, television, and much more — and there’s no clear way to disrupt

it.

But

the war for the commanding heights of the internet is far from over.

There are many players on this global chess board. Governments. Telecom

monopolies. Internet giants like Google and Facebook. NGOs. Startups.

Hackers. And — most importantly — you.

The

war for the open internet is the defining issue of our time. It’s a

scramble for control of the very fabric of human communication. And

human communication is all that separates us from the utopia that

thousands of generations of our ancestors slowly marched us toward — or

the Orwellian, Huxleyan, Kafkaesque dystopia that a locked-down internet

would make possible.

By

the end of this article, you’ll understand what’s happening, the market

forces that are driving this, and how you can help stop it. We’ll talk

about the brazen monopolies who maneuver to lock down the internet, the

scrappy idealists who fight to keep it open, and the vast majority of

people who are completely oblivious to this battle for the future.

In Part 1, we’ll explore what the open internet is and delve into the history of the technological revolutions that preceded it.

In Part 2, we’ll talk about the atoms.

The physical infrastructure of the internet. The internet backbone.

Communication satellites. The “last mile” of copper and fiber optic

cables that provide broadband internet.

In Part 3, we’ll talk about bits.

The open, distributed nature of the internet and how it’s being

cordoned off into walled gardens by some of the largest multinational

corporations in the world.

In Part 4, we’ll explore the implications of all this for consumers and for startups. You’ll see how you can help save the open internet. I’ll share some practical steps you can take as a citizen of the internet to do your part and keep it open.

This is a long read. So grab a hot beverage and get ready to download a massive corpus of technology history into your brain.

Part 1: What is the open internet?

There’s only one word to describe the open internet: chaos.

The

open internet is a cacophony of 3 billion voices screaming over one

another. It’s a dusty, sprawling bazaar. And it’s messy. But it has

produced some of the greatest art and industry of our time.

The open internet is a Miltonian marketplace of ideas, guided by a Smithian invisible hand of free-market capitalism.

The

open internet is distributed. It’s owned in part by everyone and in

whole by no one. It exists largely outside of the boundaries of

governments. And it’s this way by design.

This reflects the wisdom of Vint Cerf, Bob Khan, J. C. R. Licklider, and all the wizards who stayed up late

and pioneered the internet. They had seen the anti-capitalist,

corporatists fate that befell the telegram, the telephone, the radio,

and the TV. They wanted no part of that for their invention.

The open internet is a New Mexico Quilter’s Association. It’s a Jeremy Renner fan club. It’s a North Carolina poetry slam. It’s a Washington D.C. hackerspace. It’s a municipal website for Truckee, California. It’s a Babylon 5 fan fiction website.

The

open internet is a general purpose tool where anyone can publish

content, and anyone can then consume that content. It is a Cambrian

Explosion of ideas and of execution.

Can

these websites survive in a top-down, command-and-control closed

internet? Will they pay for “shelf space” on a cable TV-like list of

packages? Will they pay for a slice of attention in crowded walled

gardens?

We’re all trapped in The Cycle

Here’s

a brief history of the information technologies that came before the

internet, and how quickly corporations and governments consolidated

them.

Originally

anyone could string up some cable, then start tapping out Morse Code

messages to their friends. The telegram was a fun tool that had some

practical applications, too. Local businesses emerged around it.

That changed in 1851 when Western Union strung up transcontinental lines and built relay stations between them.

If

small telegraph companies wanted to be able to compete, they needed

access to Western Union’s network. Soon, they were squeezed out

entirely.

At

one point Western Union was so powerful that it was able to

single-handedly install a US President. If you grew up in America, you

may have memorized this president’s name as a child: Rutherford B.

Hayes.

Not

only did Western Union back Hayes’ campaign financially, it also used

its unique position as the information backbone for espionage purposes.

It was able to read telegrams from Hayes’ political opponents and make

sure Hayes was always one step ahead.

Western

Union’s dominance — and monopoly pricing — would last for decades until

Alexander Graham Bell disrupted its business with his newly-invented

telephone.

How the telephone fell victim to The Cycle

After

a period of party lines and local telephone companies,

AT&T — backed by JP Morgan — built a network of long-distance lines

throughout America.

In

order for the customers of local phone companies to be able to call

people in other cities, those companies had to pay AT&T for the

privilege of using its long-distance network.

Theodore

Vail — a benevolent monopolist if there ever was one — thought that

full control of America’s phone systems was the best way to avoid messy,

wasteful capitalistic competition. He argued that his way was better

for consumers. And to be fair, it was. At least in the short run.

Vail

was able to use AT&T’s monopoly profits to subsidize the

development of rural phone lines. This helped him rapidly connect all of

America and unify it under a single standardized system.

But

the problem with benevolent monopolists is they don’t live forever.

Sooner or later, they are replaced by second-generation CEOs, who often

lack any of their predecessors’ idealism. They are only after one

thing — the capitalist’s prerogative — maximizing shareholder value.

That means making a profit, dispersing dividends, and beating quarterly

earnings projections. Which means extracting as much money from

customers as possible.

AT&T

eventually squeezed out their competitors completely. And once

AT&T’s monopoly became apparent, the US Government took action to

regulate it. But AT&T was much smarter than its regulators, and

jumped on an opportunity to become a state-sponsored “natural monopoly.”

AT&T would enjoy monopoly profits for decades before being broken up by the FCC in 1982.

But the “baby bells” wouldn’t stay divided for long. In 1997, they were able to start merging back together into a corporation even bigger than before the break-up.

The

end result is one of the most powerful corporations on the

planet — strong enough to expand its monopoly from the land-line

telephone industry to the emerging wireless telecom industry.

AT&T

functioned like a branch of government and had extensive research labs,

but with one major exception — it could keep secret any inventions that

it perceived as a threat to its core business.

Voicemail

— and digital tape, which was later used as a critical data storage

medium for computers — was actually invented within one of AT&T’s

labs in 1934. But they buried it. It was only re-invented decades later.

Imagine

how much progress the field of information technology could have made

during that length of time with such a reliable and high-volume data

storage medium at its disposal.

To

give you some idea of how much just this one AT&T decision may have

cost humanity, imagine that a corporation purposefully delayed the

introduction of email by a decade. What would be the total impact on the

productivity of society? How many trillions of dollars in lost economic

activity would such an action cost us? This is the

cautionary tale of what happens when you leave scientific research and

development to private industry instead of public labs and universities.

You

can still feel the legacy of AT&T’s monopoly when you call an older

person from out of state. They will instinctively try to keep the call

as short as possible, because they want to avoid the massive long

distance fees historically associated with such calls, even though these

no longer apply.

I

thought this was just my grandmother, but it’s everyone’s grandmother.

Entire generations have been traumatized by AT&T’s monopolistic

pricing.

How cinema fell victim of The Cycle

Shortly

after the invention of cinema, we had thousands of movie theaters

around the US showing a wide variety of independently-produced films on

all manner of topics. Anyone could produce a film, then screen it at

their local theater.

That

changed when Adolf Zukor founded Paramount Pictures. He pioneered the

practice of “block booking.” If small independent theaters wanted to

screen, say, the newest Mae West film, they would also need to purchase

and screen a bunch of other lessor films.

This

took away theater owners’ status as local tastemakers, and removed

their ability to cater to their own local demographics. The result was

the commoditization of movie theaters, and ultimately the rise of

blockbuster cinema.

How radio fell victim to The Cycle

Shortly after Marconi — or Tesla

— invented the radio, a massive hobbyist movement sprung up around it.

There were thousands of local radio stations playing amateur programs.

In

stepped David Sarnoff as the head of the Radio Corporation of America

(RCA). He was perhaps the most Machiavellian CEO of the 20th century.

At

the time, RCA was making parts for radio. Conventional thinking at the

time was that RCA should focus on hardware, and getting as many radio

stations running and as many radios into homes as possible. But Sarnoff

realized that the real money was in content. He helped popularize the

National Broadcast Corporation (NBC) and focused instead on making money

through advertisements.

Then

Sarnoff approached the Federal Radio Commission — now the Federal

Communications Commission (FCC) — and convinced them that since the

radio spectrum was a scarce commodity, they should carve it up and issue

licenses.

Soon,

NBC was available in every home, and the local hobbyist radio stations

were squeezed off the air. RCA was now vertically integrated — from the

parts in the radio stations, to the parts in consumer radios, to the

content being broadcast itself.

Sarnoff

had talked with the inventors of TV, and knew that it would eventually

disrupt radio. But he had a plan. To claim the invention of television

for himself.

How TV fell victim to The Cycle

TV

is different from other forms of technology here, in that it didn’t

enjoy a hobbyist stage. With the help of the FCC, Sarnoff and RCA

immediately locked TV down. The result was several decades where

Americans had just three channels to choose from — NBC, CBS, and ABC.

This

was the height of mass culture — half of all Americans watching the

same episode of I Love Lucy at the same time. The popularity of

television — combined with the lack of diversity in programming caused

by this monopoly — had social and political consequences that haunt us

to this day.

Will the open internet fall victim to The Cycle?

We’ve gone through the invention step. The infrastructure came out of DARPA and the World Wide Web itself came out of CERN.

We’ve gone through the hobbyist step. Everyone now knows what the internet is, and some of the amazing things it’s capable of.

We’ve gone through the commercialization step. Monopolies have emerged, refined, and scaled the internet.

But

the question remains: can we break with the tragic history that has

befallen all prior information empires? Can this time be different?

Part 2: The War for Atoms

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” — Arthur C. Clarke’s Third Law

As

much as we may think of the internet as a placeless realm of pure

abstractions, it has a physical structure. It’s not magic. And more

people are waking up to this reality each day.

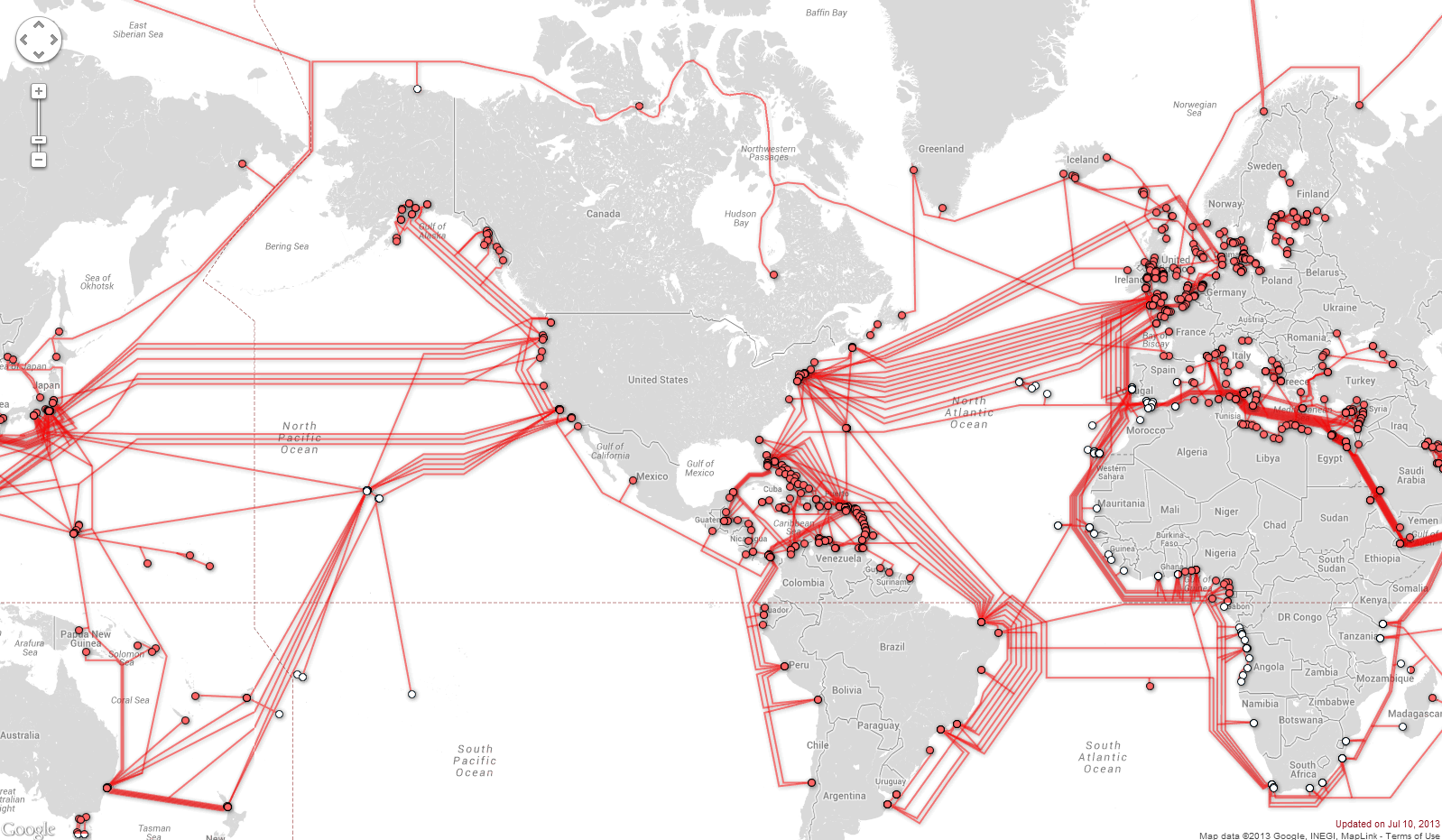

The

internet is a series of copper and fiber optic cables that burrow

through the ground and tunnel under oceans. We call this the Internet

Backbone. Here’s what it looks like:

The

internet is then further distributed through regional backbones. Here’s

all the fiber that carries internet data around the United States. Red

squares represent the junctions between “long haul” fibers.

Infrastructure

The invisible workhorses of the internet: backbone providers

Six major companies control the backbone, and they “hand off” traffic from one another without any money exchanging hands:

- Level 3 Communications

- Telia Carrier

- NTT

- Cogent

- GTT

- Tata Communications.

Within

the US, the backbone is mostly controlled by old long distance

carriers, including Verizon and AT&T — who also control a two thirds

of America’s $200 billion wireless industry.

These

companies “peer” traffic through backbone connections controlled by

other companies, or pay each other through “transit agreements.”

Despite the involvement of these huge telecoms, the internet backbone represents a fairly healthy market. About 40% of the internet’s backbone is controlled by smaller networks you’ve never heard of.

The mafia of the internet: the ISPs

The

broadband internet market, on the other hand, isn’t healthy at all.

This is the “last mile” of cables that plug into the internet backbone.

And it’s full of ugly tollbooths, guarded by thick benches of lawyers

and lobbyists.

This

broadband internet market is controlled by just three extremely

powerful — and widely hated — internet service providers (ISPs):

- Cox

- Charter (which recently acquired another ISP, Time Warner)

- and the most hated corporation in America, Comcast, which controls 56% of America’s broadband

Another form of ISPs are the wireless providers:

- AT&T

- Verizon (formerly part of AT&T)

These

two providers control 2/3rd of the wireless market. If you have a

mobile phone, there’s a good chance you pay one of these companies every

month for your data plan.

These

ISPs control millions of miles of copper cables that they buried in the

ground back in the 1970s, and satellites they shot up into orbit in the

1990s. They constantly break the law,

tie up regulators in lengthy court battles, and make it practically

impossible for anyone — even Google — to enter their markets.

The

ISPs do all this for one reason and one reason alone: so they can avoid

free market competition — and the expensive technology upgrades it

would require — while they continue raking in their monopoly rents from the 2/3 of Americans who only have one choice in their neighborhood for broadband internet.

For

the past two years, the public had a weapon against these ISPs. It’s

not one that can mortally wound them , but it has helped beat back their

monopolistic tendencies. It’s called Net Neutrality.

How Net Neutrality works

The

story of ISPs basically comes down to this: They used to make a ton of

money off of cable packages. But people discovered that once they had

the internet, they didn’t care about cable TV any more — they just

wanted data plans and so they could watch YouTube, Netflix, or whatever

shows they wanted — and they could also consume a lot of non-video

content, too.

The

ISPs don’t make nearly as much selling you a data plan as they used to

make selling you a cable plan, though. So their goal is to return to the

“good old days” by locking down the internet into “channels” and

“bundles” then forcing you to buy those.

How

do we prevent this? The good news is that we already have. In 2015, the

FCC passed a law that regulated ISPs as utilities. This is based on the

principle of “Net Neutrality” which basically states that all

information passing through a network should be treated equally.

As

part of its 2015 decision on Net Neutrality, the FCC asked for public

comment on this topic. 3 million Americans wrote to the FCC. Less than 1% of those people were opposed to Net Neutrality.

After a hard fought battle against telecoms, we convinced the FCC to enshrine Net Neutrality into law.

The FCC’s Title II regulation created three “bright lines” that prevent ISPs from doing the following:

- Blocking content from websites

- Slowing down content from websites

- Accepting money from websites to speed up their content

These

rules made it so that no matter how rich and powerful a corporation

is — and Apple and Google are the biggest corporations on Earth, and

Microsoft and Facebook aren’t far behind — they can’t buy priority

access to the internet.

Everyone

has to compete on a level playing field. These tech conglomerates have

to compete with the scrappy startups, the mom-and-pop businesses, and

even independent bloggers who are running WordPress on their own domain.

Nobody

is above Net Neutrality. It’s as simple a tool as possible for

protecting the capitalist free market internet from monopolies who would

otherwise abuse their power.

Now

ISPs are treated like a utility. How are the packets being routed

through a network different from the water being piped through the

ground, or the electricity flowing through a power grid?

The water company shouldn’t care whether you’re turning on a tap to wash dishes or to take a shower.

The power company shouldn’t care whether you’re plugging in a TV or a toaster.

The ISPs shouldn’t care what data you want or what you use it for.

The

reason ISPs want to get rid of Net Neutrality is simple: if we stop

treating them like the utility that they are, they can find ways to

charge a lot more money.

Here’s the former CEO of AT&T laying out his evil plan:

“Now what they would like to do is use my pipes free, but I ain’t going to let them do that because we have spent this capital and we have to have a return on it. So there’s going to have to be some mechanism for these people who use these pipes to pay for the portion they’re using. Why should they be allowed to use my pipes? The Internet can’t be free in that sense, because we and the cable companies have made an investment and for a Google or Yahoo! or Vonage or anybody to expect to use these pipes [for] free is nuts!” — Edward Whitacre, AT&T CEO

What

he should certainly realize is that everyone is already paying for

internet access. You’re paying to be able to access this article. I’m

paying to push this article up onto the internet. This website is paying

to send the traffic from its servers over to your computer.

We have all already paid to use these ISP’s last mile of cables. No one is using these pipes for free.

But

the ISPs see an opportunity to double dip. They want to charge for

bandwidth, and also charge websites what the Mafia calls “protection

money.” They essentially want to be able to say to website owners:

“Those are some lovely data packets you’ve got there. It sure would be a

shame if they got lost on their way to your users.”

Of

course, most of the open internet couldn’t afford to pay this

“protection money” to ISPs, so the ISPs would block traffic to their

websites, cutting consumers off from most of the open internet. But the

ISPs wouldn’t need to block these websites. All the ISPs would need to

do is introduce a slight latency.

Both

Google and Microsoft have done research that shows that if you slow

down a website by even 250 milliseconds — about how long it takes to

blink your eyes — most people will abandon that website.

That’s

right — speed isn’t a feature, it’s a basic prerequisite for attracting

an audience. We humans are extremely impatient and becoming more so

with each passing year.

This means that in practice, if an ISP artificially slows down a website, it’s practically as damaging as blocking the site entirely. Both of these acts result in the same outcome — a severe loss of traffic.

Traffic

is the lifeblood of websites. Without traffic, merchandise doesn’t get

sold. Services don’t get subscribed to. Donations don’t get made.

Without traffic, the open web dies — whether ISPs block it or not.

The ISPs have launched an all-out assault on Net Neutrality

With January’s change in US administration and the election of our 45th president, the FCC has changed as well.

The

FCC Chairman Ajit Pai — a former Verizon lawyer — is now in control of

the only regulator that the ISPs answer to. And here’s a direct quote

from him:

“We need to fire up the weed whacker and remove those rules that are holding back investment, innovation and job creation.” — FCC Chairman Ajit Pai

The

ISPs won’t reinvest their “protection money” in infrastructure. They

already have incredible monopoly profits. Here’s their net income

(after-tax profits) from 2016:

- AT&T: $16 billion

- Verizon: $13 billion

- Comcast $8 billion

- Charter $8 billion

They

have plenty of profit they could claw back into improving

infrastructure. They’re choosing instead to disperse this money to

shareholders.

In just two months, Chairman Pai has already done incredible damage to Net Neutrality. He dropped Zero Rating

lawsuits against four monopolies who were in clear violation of Net

Neutrality law. Now Comcast and AT&T can continue to stream their

own video services without them counting toward customers’ data caps,

and there’s nothing the FCC will do about it.

Former

FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler did his best to reach out to Chairman Pai and

convince him of the virtues of Net Neutrality. The two were scheduled to

meet once every two weeks during Wheeler’s last 18 months in office.

But Pai cancelled every single one of these meetings.

“You have to have open networks — permissionless innovation. Period. End of discussion. They’re crucial to the future.” — Former FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler

Part 3: The War for Bits

What does a post Net Neutrality internet look like? Look no further than the Apple App store.

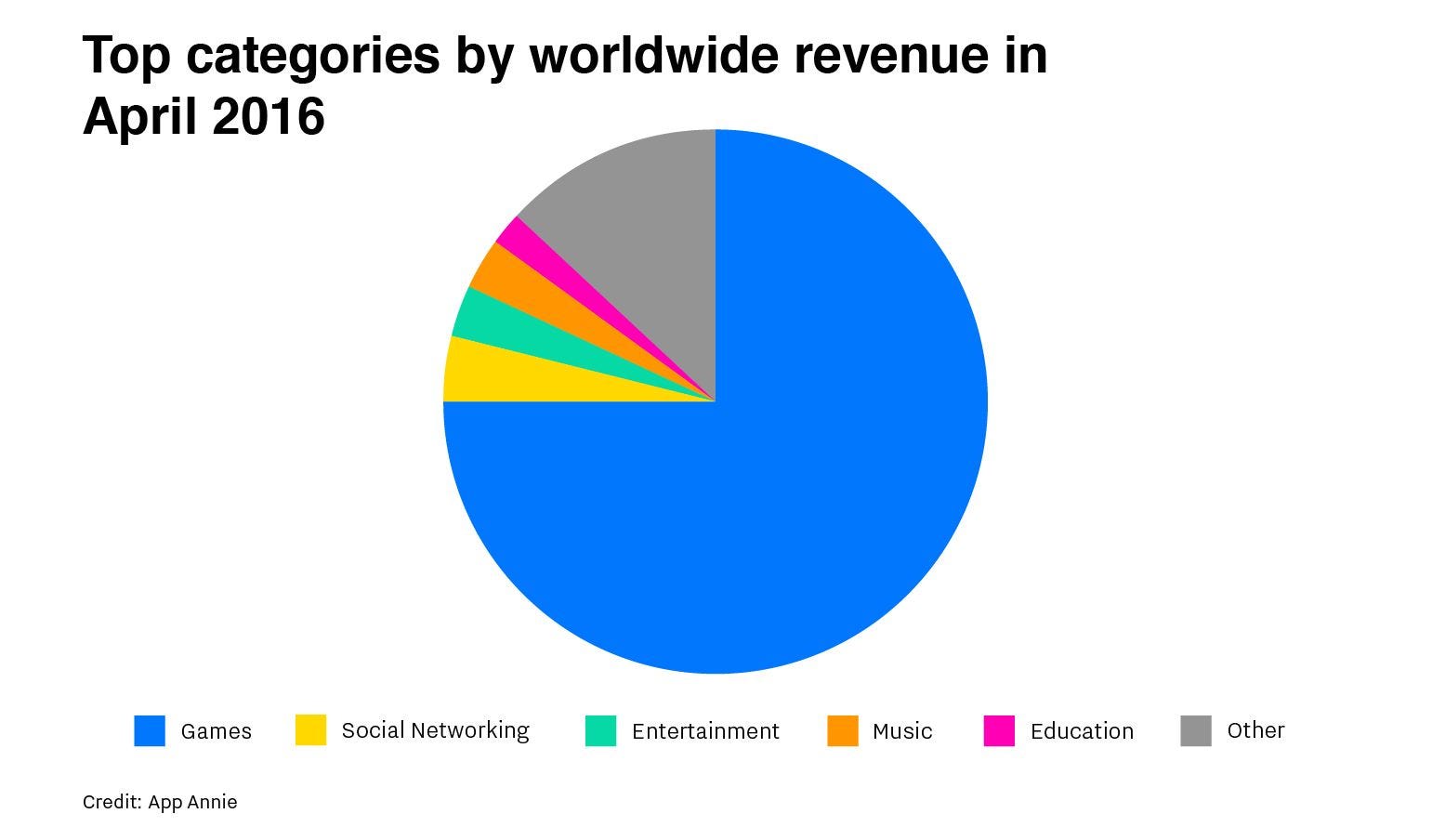

There

are two million apps in the app store, which shared a total of $28

billion in 2016. Apple takes a 30% commission on every sale, and made

$8.4 billion from the app store alone.

Most of the remaining $20 billion goes to just a small handful of mobile gaming companies:

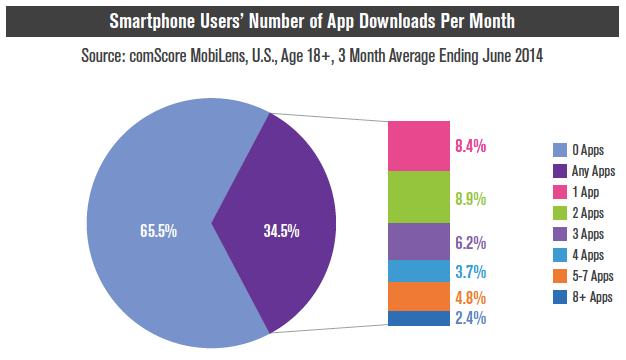

Most iPhone users download zero apps per month.

The minority who do bother to download new apps don’t end up downloading very many.

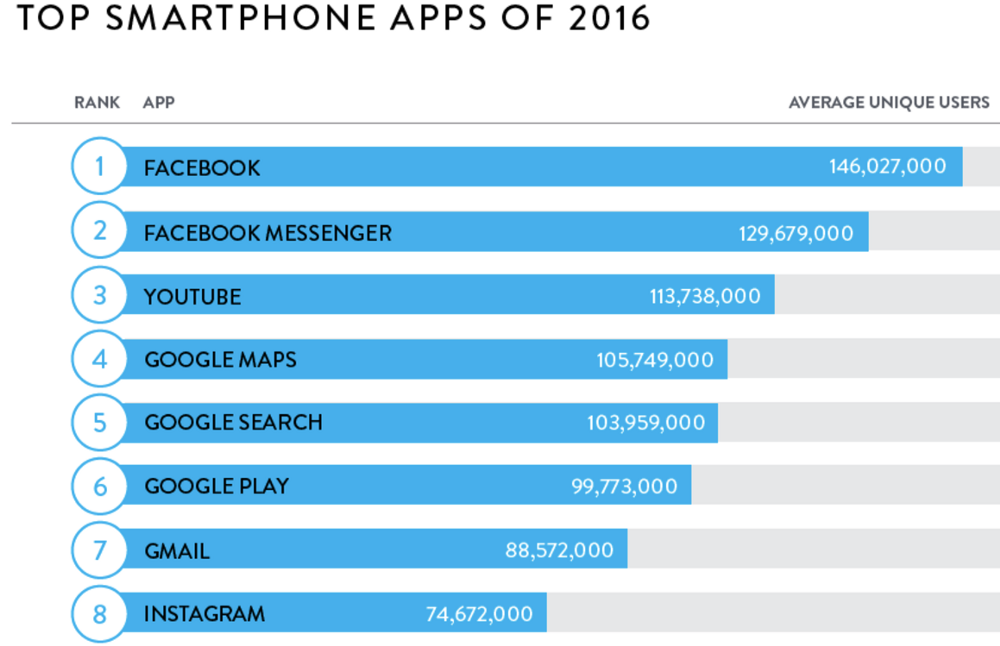

And all 8 of the top apps in the app store are owned by just two corporations: Facebook and Google.

A vast majority of the remaining 2 million apps get very little traffic — and even less money.

The

Apple App Store isn’t a level playing field. It doesn’t resemble the

open internet it was built on top of. Instead, it’s an example of a

walled garden.

Walled

gardens look beautiful. They’re home to the most popular flora. But

make no mistake, you won’t be able to venture very far in any one

direction without encountering a wall.

And

every walled garden has a gatekeeper, who uproots plants that look like

weeds. If you want to plant something in a walled garden, you have to

get approval from that gatekeeper. And Apple is one of the most

aggressive gatekeepers of all. It keeps out apps that compete with its own interests, and censors apps that don’t mesh with its corporate worldview.

A brief history of walled gardens

First there was the original walled garden of the internet, AOL.

20

years later, AOL still has 2 million users paying them $20/month.

There’s a lot of money to be made in building walled gardens and

trapping users in them.

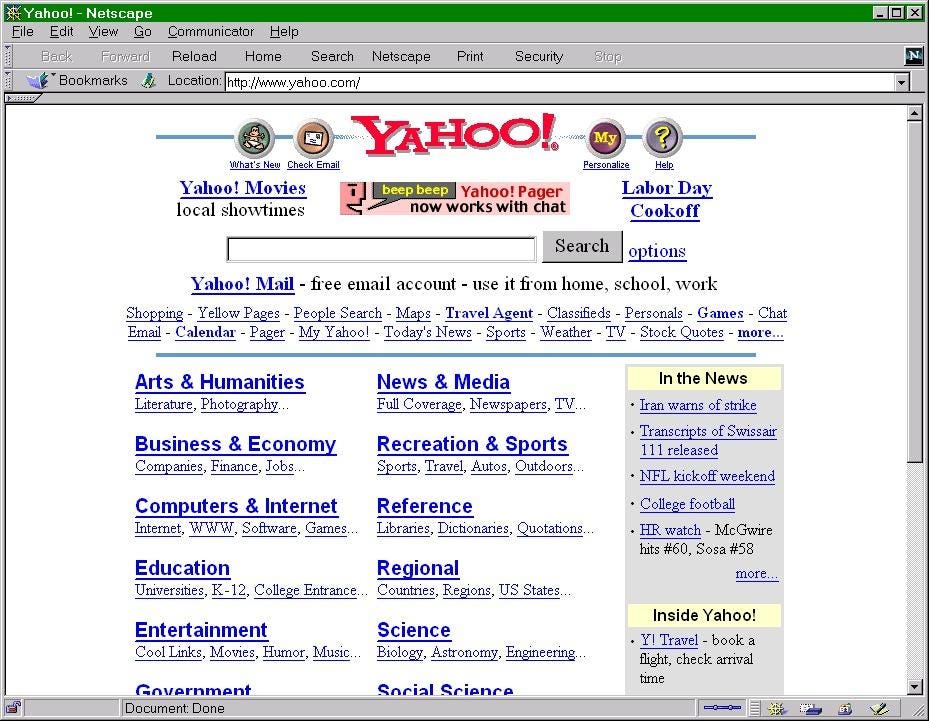

Then came Yahoo, which wasn’t a walled garden by design, but became one anyway because people were so new to the internet.

In the late 90s, startups raised money specifically so they could buy banner ads on Yahoo. It was the best way they could reach prospective users.

But Yahoo was a candle in the sun compared to the ultimate walled garden: Facebook.

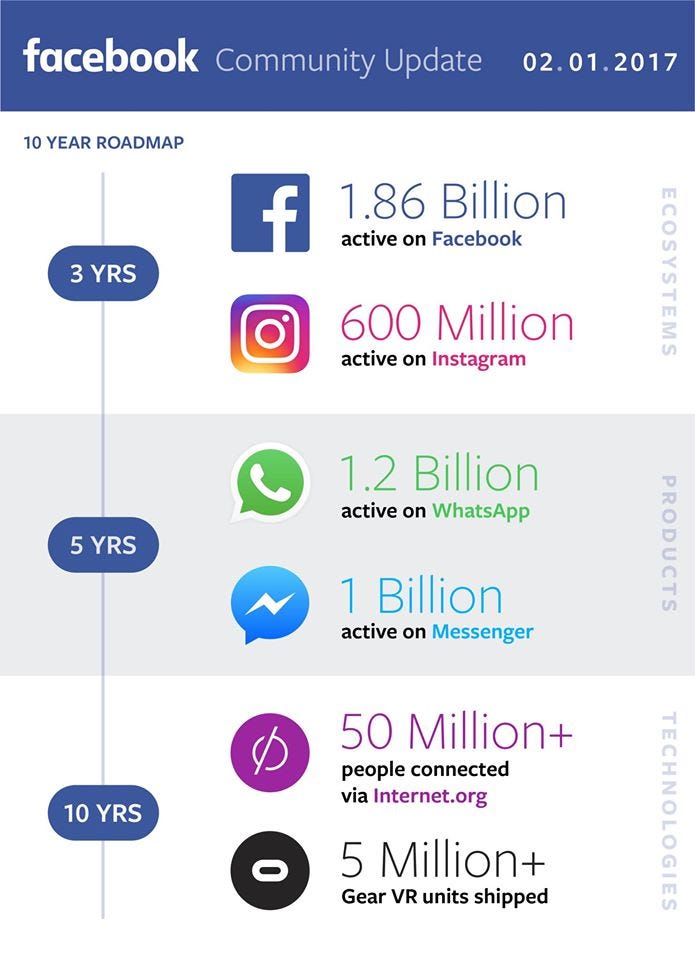

A quarter of the people on Earth use Facebook for an average of 50 minutes each day.

And

those 50 million people connected to Internet.org that Mark Zuckerberg

is bragging about? Those are people from extremely poor countries who

were given a choice: they could either pay for the open internet or just

get Facebook for free. They chose Facebook.

The insidiously-named Internet.org was famously rejected in India

— among other countries — where activists were able to raise awareness

about all the things Indians would give up by accepting Facebook instead

of the open internet.

Mark Zuckerberg may mean well, but he’s rapidly destroying the open internet. In his ravenous quest to expand Facebook’s market share, he’s even gone so far as to build a sophisticated censorship tool so that Facebook can appease the governments of countries where it’s currently blocked, like China.

And

Facebook is just one of several internet corporations who stand to

profit from these sort of closed-source, closed-data walled garden

platforms.

Here are the 10 largest corporations in the world by market capitalization:

- Apple Inc

- Alphabet (Google)

- Microsoft

- Exxon Mobil

- Johnson & Johnson

- General Electric

- Amazon.com

- Wells Fargo

- AT&T

All of them are American-based multinationals. 5 out of 10 of them are internet companies, and one of them is an ISP.

Once

you look past the last gasp of the banks and the oil companies, it

becomes clear that these internet companies are the new order. They

control information. They control the conversation. They control

politics. Facebook won the new president the election — even the president and his advisors acknowledge this.

So what makes you think they won’t come to control the very internet they dominate?

Even as the costs of launching a website fall, the costs of reaching an audience continue to rise.

Facebook and Google account for 85% of all new dollars spent on online advertising.

Everyone else — newspapers, blogs, video networks — is fighting for

crumbs — the 15% that fell from Facebook’s and Google’s mouths.

Half of all internet traffic now flows to just 30 websites. The remaining half is thinly spread across the 60 trillion unique webpages currently indexed by Google.

If you’re familiar with the concept of a long tail distribution, you’ll recognize this phenomenon as an extremely fat head with an extremely long, skinny tail.

We blindly trust tech founders to be benevolent

You

may think that the Mark Zuckerbergs and the Larry Pages of the world

would know better than to abuse their power. But such scandals have

happened in the past.

Reddit

is one of the most popular websites on the internet. One of its

founders recently put the company’s reputation in jeopardy. He admitted

that he had modified users’ comments in Reddit’s database — essentially putting words in the mouths of people who were critical of him.

We

are not only placing faith in the temperament of the elite handful of

tech company founders. We’re also trusting that other actors — who

ultimately take over these organizations — will be benevolent. Even when

we know that their shareholders — or governments — can force them to be

malevolent and do things that go against their users’ interests.

However

you may feel about Mark Zuckerberg and his intentions, know this: Just

like the “benevolent monopolist” Theodore Vail, who championed rural

access to AT&T in the early 20th century, Mark Zuckerberg will one

day retire. And the person who takes over Facebook will not be nearly as

forward thinking as he is. Most likely, it will be some finance guy or

sales guy who will sell Facebook users — and their Exabytes of

data — down the river.

By destroying Net Neutrality, the ISP monopolies are herding us all into walled gardens

If we lose net neutrality, websites that once freely operated on the open internet will face three choices:

- pay ISPs so that their customers can access their website

- don’t pay ISPs, and plummet into obscurity

- become part of a walled garden that is paying ISPs on their behalf

This

last option will be the most appealing for most small businesses. They

will choose the free option. And in doing so, they’ll hand over to the

walled gardens some amount of control over their own websites.

A

Google or a Facebook will step in to help ensure that your customers

are able to access your business’s website. These walled gardens will

pay ISPs on your behalf, and help serve your content on their own

domains. But in return, the walled garden could:

- inject ads into your website (probably ads for your competitors)

- capture your data and sell it (probably to your competitors)

- redirect your customers to the websites of competitors who are willing to pay for your audience

Just

like with Google ads or Facebook ads, the internet will become a race

to see who can pay walled gardens the most money so they can gain access

to customers. And most of this will be completely invisible to

consumers.

There are precedents for all of this.

Facebook

convinced millions of businesses to setup Facebook pages. The companies

then spent their own money publicizing their Facebook pages and getting

their customers to “like” their pages. Then Facebook pulled a

bait-and-switch, and made it so these businesses would have to advertise

through Facebook if they wanted to reach their own customers who’d

previously liked their pages.

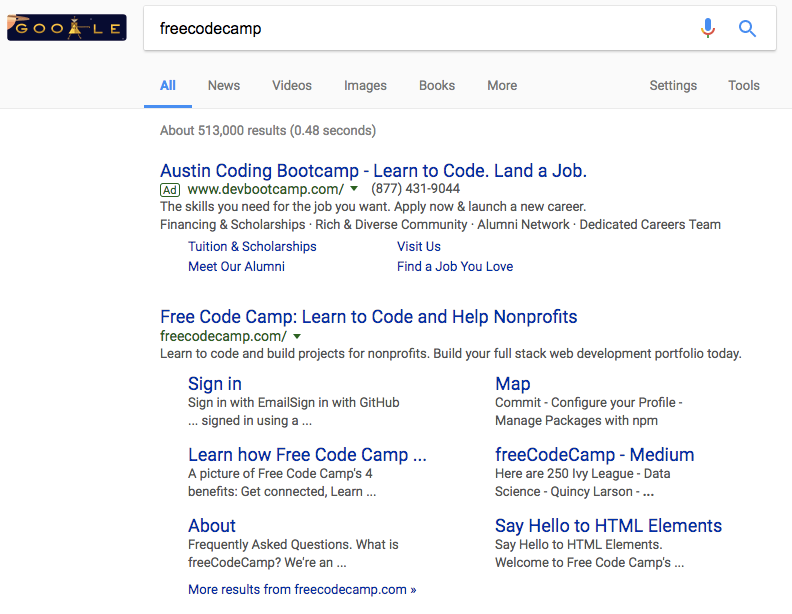

And here’s what happens when a small nonprofit like freeCodeCamp refuses to pay for Google ads:

Companies

with lots of money like this one — which is a subsidiary of Kaplan, one

of the largest for-profit education conglomerates on earth — can pay

money to Google so they can intercept our users.

And

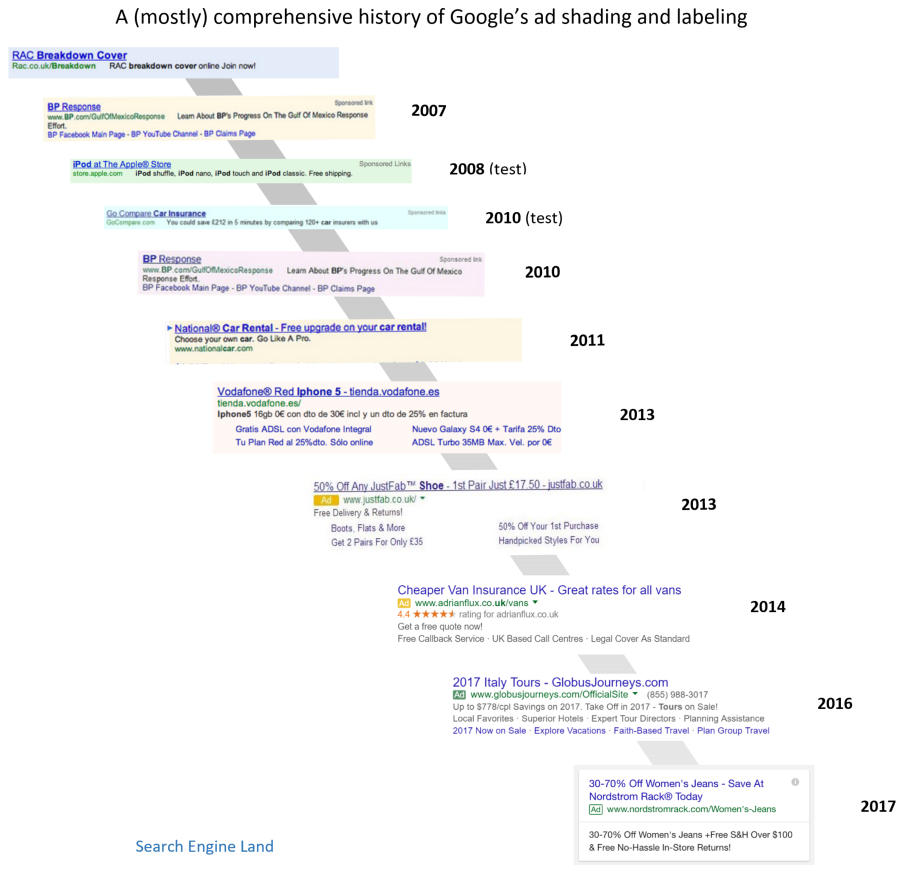

these ads will gradually look less and less like ads. Here’s how Google

ads have changed over time to look more and more like normal search

results:

Now

that tiny, green-bordered box with the word “ad” in it is all that

distinguishes an advertisement from a legitimate search result. It is

perhaps unsurprising that 55% of Google users don’t even recognize the fact that these are ads.

Eventually

walled gardens may converge on something similar to Baidu, China’s

largest search engine, which for a long time wasn’t labelling ads at

all.

Baidu got into trouble last year

after a college student used their search engine to seek treatment for a

commonly treatable form of cancer. The student went to a hospital he

found at the top of Baidu’s search results.

What

the student didn’t know was that that hospital had paid Baidu money to

be put at the top of the search results, and that this was in fact an

advertisement. But Baidu had deliberately obscured this fact from their

users so they could charge more for the ad.

The

hospital proceeded to recommend an expensive and unproven drug instead

of the standard — and far cheaper — treatment of surgery and

chemotherapy.

After

exhausting his family’s savings of $30,o00 on the ineffective

treatment, the 21-year-old student wrote one final essay about his

situation and how Baidu had lead him right into the hands of fraudsters.

Then he died.

This

is just a glimpse into the human toll that these walled gardens can

inflict upon society. In a walled garden environment where only those

who pay money get seen, consumers will face more misinformation, more

fraud, and more needless suffering.

Instead

of the equalizing force that was the open internet, the rich will get

richer and the poor will get poorer. The internet’s promise of economic

democratization will fall by the wayside, and we’ll enter yet another

age of peasants living under feudal lords.

In the future, our internet could become as locked-down as China’s

China

has the most sophisticated censorship tools in the world. So much so

that other authoritarian regimes license the use of these tools to

control their own populations.

1.4 billion Chinese people are trapped in a closed internet, behind the Great Firewall of China.

The

anti-Net Neutrality agenda that the ISPs are pursuing would require

them to use a technique called Deep Packet Inspection. Without looking

inside the contents of every packet, it’s impossible for an ISP to

decide which packets they want to selectively slow down.

This

means that in addition to sending packets of data through their

networks, ISPs would actually have to look inside each of these

packets — and would quite likely record the contents of these packets.

It would be expensive, but storing major chunks of the Zettabyte of

information the internet generates each year is within the budgets of

large corporations and governments.

There’s a precedent for this, too. AT&T illegally monitored all of its traffic for years.

Monitoring

internet traffic at this level of detail would make pervasive

censorship possible. This is one of the techniques China uses to

re-write its history. And it works. Despite the advances in information

technology, to this day many Chinese still don’t know that the Tiananmen Massacre happened. And when they do learn of it, it’s ancient history — sapped of most of its perceived relevance.

“Ideas are more powerful than guns. We would not let our enemies have guns, why should we let them have ideas.” — Joseph Stalin

If

the ISPs succeed and the open internet falls, corporations and

governments would have a mandate to censor the most powerful

communication tool in human history — the internet — in its entirety.

Part 4: Who controls the information? Who controls the future?

Whether

these corporations are aggregating power through regulatory capture or

by amassing exabytes of your data, they are steadily becoming more

powerful. They are using their growing cashflow to buy up competitors.

This isn’t capitalism — it’s corporatism.

Capitalism is messy. It’s wasteful. But it’s much healthier in the long

run for society than central planning and governments trying to pick

the winners.

Capitalism allows for small businesses to enter the arena and actually stand a chance. Corporatism makes that unlikely.

If

you’ve read this far, I hope you understand the gravity of this

situation. This is not speculative. This is really happening. There are

historical precedents. There are present-day examples.

If

you do nothing, we will lose the war for the open internet. The

greatest tool for communication and creativity in human history will

fall into the hands of a few powerful corporations and governments.

Without your actions, corporations will continue to lock down the internet in ways that benefit them — not the public.

The

good news is that our great grandparents reined in similar monopolies.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Americans faced abusive oil,

railroad, and meat industry monopolies. We prevailed over them by

raising awareness through brave journalism, and by compelling the

government to act.

Today, our most urgent task at hand is stopping FCC Chairman Ajit Pai from disassembling Net Neutrality.

Help us fight this war. Here’s what I’m asking you to do:

- If you can afford to, donate to nonprofits who are fighting for the open internet: Free Press, the ACLU, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Public Knowledge.

- Educate yourself about the importance of the open internet. Read Tim Wu’s “The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires.” It is by far the best book on this topic.

- Contact your representatives and ask them what they’re doing to defend Net Neutrality.

- Share this article with your friends and family. I realize the irony of asking you to use walled gardens to spread the word, but this late in the game, these are the best tools available. Share this article on Facebook or tweet this article.

Only we, the public, can end The Cycle of closed systems. Only we can save the open internet.

No comments:

Write comments