It’s both more serious and less serious than we’ve admitted

I’ve

recently seen a lot of very anxious responses from people in tech at

anything which suggests that their “core skills” may be devalued,

especially in favor of other skills which they haven’t spent their lives

on. Most importantly, this shows up in the argument over “hard” versus

“soft” skills. That anxiety is itself a signal of how important this has

become. But there’s a hidden assumption we’ve been making that (I

suspect) has increased the anxiety far out of proportion: and maybe

perversely, it comes from not taking soft skills seriously enough. Today, I’d like to share some thoughts on what’s actually happening, and a set of things we can do to help fix it for all of us.

1. Some observational data

One

of the most reliable ways I can see anxious responses on the Internet

is to suggest that soft skills may eclipse hard skills in importance for

engineers. By “anxious responses,” I don’t mean “disagreement:” I

specifically mean emotionally charged disagreement. And that emotional charge is a very important data point.

One

very reliable pattern I’ve observed in a lot of situations is that the

strength of people’s emotional response to a statement tells you a lot

about how close this statement cuts to their biggest worries. It’s sort

of obvious if you say it that way, but if you apply it as a detection

method, it’s very powerful: strong responses lead you to where the real

problems are, the real threats to people.

(This

trick is shamelessly stolen from psychology, specifically from

psychotherapy, where it’s a reliable way to figure out which issues are

most salient to someone. A good rule of thumb is, the harder something

is to talk about, the more likely that it’s important. It has many other

applications, as well; for example, if you find people very offended by the suggestion that they might be or like something,

that’s often a sign that this “something” is closely associated with a

group that they’re similar enough to that they’re at risk of being

mistaken for it, but that they have a very strong reason not to want to

be affiliated with.)

What’s interesting in this case is that people are so

concerned about the relative value of soft and hard skills, and not,

say, overall economic fluctuations or an oversupply of engineers, two

other things which could just as easily threaten an engineer’s status.

We

can treat the frequency of strong emotional responses as a sort of

covert wisdom-of-the-crowds signal. With regards to cultural matters,

the wisdom of crowds is an even better signal than it is in general,

because the culture is made up of those very same crowds. Reading the

pattern of conversations and responses over the past few years, the

scale of anxiety I see when the issue comes up suggests a pattern: lots

of people have the gut instinct that the rise of “soft skills” is going

to be big, but are afraid of what that may mean for them.

2. What‘s going on beneath that

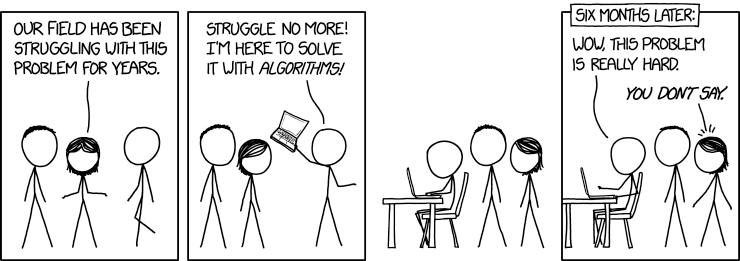

Stepping

back a bit, it’s not horribly surprising that it would be big. The

reason the “brilliant, irascible loner” has become increasingly rare is

that very little technology is built by a single pair of hands anymore.

My previous job consisted, in no small part, of trying to build and

maintain a consensus among hundreds, sometimes even thousands, of

people, in order to keep everyone moving in one direction. This was

something extremely difficult; like most people in the field, it’s very

far from what I was trained for, and I had the perpetual sense that I

was faking it and hoping nobody would notice.

When

you’re working with large groups of people, communication and

collaboration complexities quickly become the dominant factor in success

or failure. Concepts like “psychological safety” and “mutual trust”

become the things that dominate your day-to-day work far

beyond any specific technical challenge. At the junior level, it’s

because this affects your quality of life: trying to do good technical

work while surrounded by people who hate you is both difficult and

awful. At more senior levels, this becomes more and more of your

responsibility to manage and create. This is closely tied to the deeper

difference between junior and senior roles: a junior person’s job is to

find answers to questions; a senior person’s job is to find the right

questions to ask. The number of purely technical questions requiring any

given level of expertise decreases relatively sharply once you pass a

certain threshold, and the increasing prevalence of everything from

reliable compilers to Stack Exchange means that more and more of the

hard technical questions are straightforward to answer.

[Bad management] is a field that was built up out of people who often believed that they had good soft skills, while actually having atrocious ones. The simple fact that people feel not respected by their managers should be a tremendous red flag.

There

always remain various hard ones, of course, which are critical and

which can’t be solved by any number of inexperienced people except by

them getting experience; that’s why we need to continue to build and

grow our technical skills. But if you continue to grow your skillset,

you’ll quickly discover that the amount of time that needs to be spent

on these extremely difficult technical problems tends towards

significantly less than a full-time job; instead, the crucial (and

incredibly hard) problems that affect a system have more to do with how

that system interacts with the outside world — which is, more and more,

people.

Interestingly,

there’s a lot more crossover between hard and soft skills than many

people realize: when you start to see your system as a component of a

larger system which includes humans as elements, and you start to ask

how humans interact with each other and what their behaviors are, then

many of the same “hard skills” systems design approaches not only make

sense, but can provide even better answers to traditionally purely

“soft” questions. Abuse prevention on multi-user systems and result

ranking of all sorts are two classic examples; in both cases, the

ability to convert freely between very “soft” intuitions about what

people want and very “hard” mathematical expressions of those same

intuitions is priceless.

But

beyond the cases where soft and hard skills overlap within the

technical work itself, a lot of the “soft skills” being required now

have a lot more to do with people management. This is a field which

historically has a bad rep among engineers, because it’s historically

been done by people who had no engineering skills, and crucially, who

lacked respect for said skills

or the people who had them. This is because a lot of management came out

of the early 20th-century version of industrial management, the same

field that gave us phrases like “human resources:” the workers are an

annoyance and an expense, something which has to be “managed” to keep

production quotas high.

This

kind of “management” — I use the term loosely — doesn’t constitute good

soft skills, either. It’s a field that was built up out of people who

often believed that they had

good soft skills, while actually having atrocious or even actively

pathological ones. The simple fact that people feel not respected by

their managers should be a tremendous red flag: a manager’s basic job,

after all, is to coordinate people and get them to work as a team, and

if they can’t hack the most basic aspects of mutual respect themselves, there’s no way they’re going to be able to create that for everyone.

The

fact is that the kinds of “soft skills” we’re talking about aren’t the

ones that come for free to anybody; they’re not the things taught in

“manners classes” or in fraternity hazings. They come from studying

people, paying attention to them, and understanding what they need even

when they can’t express it themselves — and as such are as brutally

difficult a set of skills to acquire as any other professional

expertise. Our habit of treating them like they’re not “real” skills, of

trying to deprofessionalize and devalue them, does us no favors; when

we’re called upon to do them ourselves, we quickly find out that they’re

not trivial.

(I’m

reminded of a Certain Engineer I Know who, when moving the team into a

new building, made the fateful statement that interior architecture

should be easy, he’s an engineer, he doesn’t need to get someone else to

do this. The results were certainly interesting.

Engineers, scientists, and executives all seem prone to the disease of

believing that everyone else’s speciality should be easy.)

3. Good news: there’s a way out.

I

think there is one very “simple” thing we can do to improve this

situation: start to treat these skills like serious professional skills,

value them as such, and both train and hire people for having

them — the exact same way we do with every other critical skill.

A

good first step is to make sure we have, and share, a language for it.

It’s very hard to value something you can’t name. Some common tasks

which we often ignore are “make it possible for everyone to see what’s

going on in the project at once,” “create a shared language for the core

technical ideas so that everyone can explain the same thing,” “make

sure that everyone’s voice is heard, and that important warnings don’t

get lost because someone didn’t feel safe saying so,” and “make sure all

the stakeholders feel a sense of personal ownership in the project and

that their success is tied to its success.” (There are many more) Some

common measures which we often ignore are “how often will a

user/customer experience frustration or negative emotions while using

this product, and how does that affect their long-term usage?,” or “when

someone has a negative experience using the product, what is the

following experience on each time scale from 10ms to one week, and how

does that affect their experience of the product?”

None

of the things in that previous paragraph are new: in fact, they’re all

tied to professional specialities, from project management to user

experience research. But if a team as a whole treats these as side

things rather than as core to their success or failure, they can easily

end up in the middle of a disaster: milestones missed, different groups

building subtly different systems which only clash during final

integration, a critical problem being ignored until it’s too late, a

project being subtly sabotaged because one team actually didn’t want it

to succeed, users hitting one “small” bug and revolting in horror

(leading to anything from mass exodus to legal and regulatory action),

slow erosion of user trust. I’ve seen projects fail for every one of

these reasons — even projects where the purely “technical” aspects of

the engineering were beyond reproach.

To

treat such things as core rather than peripheral, we would expect that

everyone on the team have at least basic knowledge of them, enough to

evaluate their significance even if they aren’t the person running it

themselves. These need to be considered parts of roles on the team, just

like front-end engineering, back-end engineering, security, and site

reliability, and the team needs to think about who’s going to be

covering which job.

It

is more than OK for each engineer to not be individually able to do all

of these jobs. In fact, it would be stunning if any one person could

do all of these jobs. But if we treat some of these jobs as “invisible

labor,” unvalued and unaccounted-for, with skills we pretend don’t

exist, all we do is shoot ourselves in the foot.

We

do this in the obvious way by not provisioning for them. But we do it

in a less obvious way, by frightening ourselves unnecessarily. The

anxiety that this story began with is a symptom that we all know that

something is profoundly missing, and that this missing thing is becoming

more and more important. If we treat this missing thing as “not a real

skill,” something which some people (I’ve often heard “women” and “frat

boys” given as examples, typically

not at the same time) just can do automatically while engineers can’t,

then it becomes frightening because it starts to sound like engineers

are going to get thrown out in favor of random people off the street,

who will then have no respect for the engineers at all. But if we

recognize this as being a real skill — something people practice and get

good at (or bad at) over their entire lives — we have a different

language for it. That’s the language of “Crap, our team has nobody who

knows how to do X, and we’ve been faking it really, really, badly:” a

language painfully familiar to anyone who’s worked on a project before.

It is absolutely true that a lot of the people who are best at these

skills don’t come from an engineering world, because the engineering

world has been steadily failing to train people at them for decades; but

that doesn’t mean that these people don’t have any understanding of, or

respect for, engineering.

At

the risk of stating the obvious: Someone who’s supposed to be doing a

job involving coordinating engineers, or connecting engineering systems

to users, or anything else like that who doesn’t respect engineers is

going to be terrible at that job for obvious reasons, and you shouldn’t

hire them. “This person makes the team feel miserable” is a serious red

flag, not a normal side effect of how any of these jobs work.

But

to state the flip side of this: Everyone on a project needs to value,

and to understand at least enough of the basics of to participate in,

every other skill on the project. If there’s a legal issue relevant to

the system, everyone needs to know that bit of law. If there are user

studies showing that people react well or badly to something, everyone

needs to put those into their designs. If there’s a latency constraint

which makes certain classes of product behavior impossible, everyone

needs to understand the issue. And likewise, everyone needs to

understand and value the human skills: after all, you’re building a

system

No comments:

Write comments