Sometime

in the mid-2000s, I was a freelance web developer in Philadelphia with

some pretty crappy health insurance. I started having occasional heart

palpitations, like skipped heart beats. My doctor said it was probably

not serious, but she could do tests to rule out very unlikely potential

complications for about $1,000. That seemed pretty expensive to rent a

portable EKG for a single day, so I googled around for some schematics.

Turned out you could build a basic three-lead EKG with about $5 worth of

Radio Shack parts (I no longer have the exact schematic, but something like this).

I didn’t really understand what the circuit did, but I followed the

directions and soldered it together on some protoboard, connected a 9V

battery, and used three pennies as electrodes that I taped to my chest. I

hooked the output of the device to my laptop’s line in and pressed ‘record’.

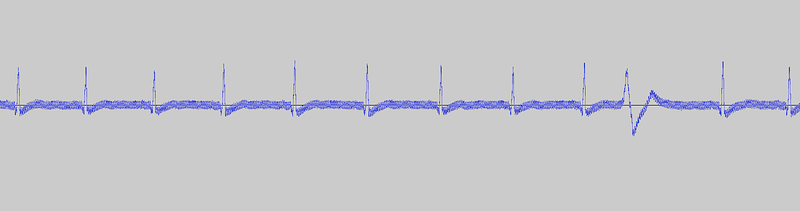

Audacity

displayed the heartbeat signal live as it recorded. Sure enough, I was

having pretty common/harmless Premature Ventricular Contractions.

There’s one on the right side of the screenshot above.

Calling

the 1/8th inch connectors you’d find on pretty much every piece of

consumer electronics until recently “audio jacks” does them a

disservice. It’s like calling your car a “grocery machine”. Headphone

and microphone ports are, at their most basic, tools for reading and

producing voltages precisely and rapidly over time.

My

homemade EKG is a voltage converter. Electrodes attached to points

around my heart measure tiny differences in voltage produced by signals

that keep it beating. Those measured signals are amplified to about plus

or minus 2 volts. That new voltage travels through an audio cable to

the “Line In” on my sound card.

Sound cards happen to carry sound most of the time, but they are perfectly happy measuring any AC

voltage from -2 to +2 volts at 48,000 times per second with 16 bits of

accuracy. Put another way, your microphone jack measures the voltage on a

wire (two wires for stereo) every 0.2 milliseconds, and records it as a

value between 0 and 65,535. Your headphone jack does the opposite, by applying a voltage between -2 and +2 to a wire every 0.2 milliseconds, it creates a sound.

To

any headphone jack, all audio is raw in the sense that it exists as a

series of voltages that ultimately began as measurements by some tool,

like a microphone or an electric guitar pickup or an EKG. There is no

encryption or rights management, no special encoding or secret keys.

It’s just data in the shape of the sound itself, as a record of voltages

over time. When you play back a sound file, you feed that record of

voltages to your headphone jack. It applies those voltages to, say, the

coil in your speaker, which then pushes or pulls against a permanent

magnet to move the air in the same way it originally moved the

microphone whenever the sound was recorded.

Smartphone manufacturers are broadly eliminating headphone jacks

going forward, replacing them with wireless headphones or BlueTooth.

We’re going to all lose touch with something, and to me it feels like

something important.

The

series of voltages a headphone jack creates is immediately

understandable and usable with the most basic tools. If you coil up some

copper, and put a magnet in the middle, and then hook each side of the

coil up to your phone’s headphone jack, it would make sounds.

They would not be pleasant or loud, but they would be tangible and

human-scale and understandable. It’s a part of your phone that can read

and produce electrical vibrations.

Without that port, we will forever be beholden to device drivers

between our sounds and our speakers. We’ll lose reliable access to an

analog voltage we could use to drive any magnetic coil on earth, any

pair of headphones. Instead, we’ll have to pay a toll, either through

dongles or wireless headphones. It will be the end of a common interface

for sound transfer that survived more or less unchanged for a century,

the end of plugging your iPod into any stereo bought since WWII.

Entrepreneurs

and engineers will lose access to a nearly universal, license-free I/O

port. Independent headphone manufacturers will be forced into a

dongle-bound second-class citizenry. Companies like Square — which made

brilliant use of the headphone/microphone jack to produce credit card

readers that are cheap enough to just give away for free — will be hit with extra licensing fees.

Because

a voltage is just a voltage. Beyond an input range, nobody can define

what you do with it. In the case of the Square magstripe reader, it is

powered by the energy generally used to drive speakers (harvesting the

energy of a sine wave being played over the headphones), and it

transmits data to the microphone input.

There’s also the HiJack project,

which makes this whole repurposing process open source and general

purpose. They provide circuits that cost less than $3 to build that can

harvest 7mW of power from a sound playing out of an iPhone’s headphone

jack. Because you have raw access to some hardware that reads and writes

voltages, you can layer an API on top of it to do anything you want,

and it’s not licensable or limited by outside interests, just some

reasonably basic analog electronics.

I don’t know exactly how

losing direct access to our signals will harm us, but doesn’t it feel

like it’s going to somehow? Like we may get so far removed from how our

devices work, by licenses and DRM, dongles and adapters that we no

longer even want to understand them? There’s beauty

in the transformation of sound waves to electricity through a

microphone, and then from electricity back to sound again through a

speaker coil. It is pleasant to understand. Compare that to

understanding, say, the latest BlueTooth API. One’s an arbitrary and

fleeting manmade abstraction, the other a mysterious and dazzlingly convenient property of the natural world.

So,

if you’re like me and you like headphone jacks, what can you do? Well,

you could only buy phones that have them, which I think you’ll be able

to do for a couple years. Vote with your dollar!

You

can also tell companies that are getting rid of headphone jacks that

you don’t like it. That your mother did not raise a fool. That aside

from maybe water-resistance,

there’s not a single good reason you can think of to give up your

headphone jack. Tell them you see what they’re up to, and you don’t like it.

You can say this part slightly deeper, through gritted teeth, if you

get to say it aloud. Or, just italicize it so they know you are serious.

No comments:

Write comments