For better or worse, we begin 2018 in the wake of some historically significant political shifts.

Across the U.S., Europe and beyond, establishment thinking and received

wisdom failed to predict the electoral upheavals of 2016. In this

piece, we explore some upheavals in the tech world that might also come

sooner rather than later, manifesting a similar reaction against

products and corporations that are increasingly perceived as both too

powerful and too self-serving.

1. Apple will enter a full-blown identity crisis

Some

might have thought that the corporate drama of Apple Computer would

have ended after the Steve Jobs era — but the controversies that have

come to characterize Tim Cook’s tenure have turned out to be just as

enthralling.

The

company Cook inherited in 2011 was very different from the one that

Jobs found when he rejoined Apple in 1997. Jobs was brought in because

the company had declined into near-irrelevance by the mid-90s; in

contrast, Cook took over one of the largest and most successful

companies in the world, boasting a highly desirable range of products

and one of the most loyal customer bases around.

So, why this prediction — that 2018 is going to herald an identity crisis for Apple?

Well,

things have been brewing for a while. First, there are the dumb design

decisions that have characterised Cook’s tenure. Don’t get us

wrong — Apple have always had a sideline in eccentric, overpriced, and

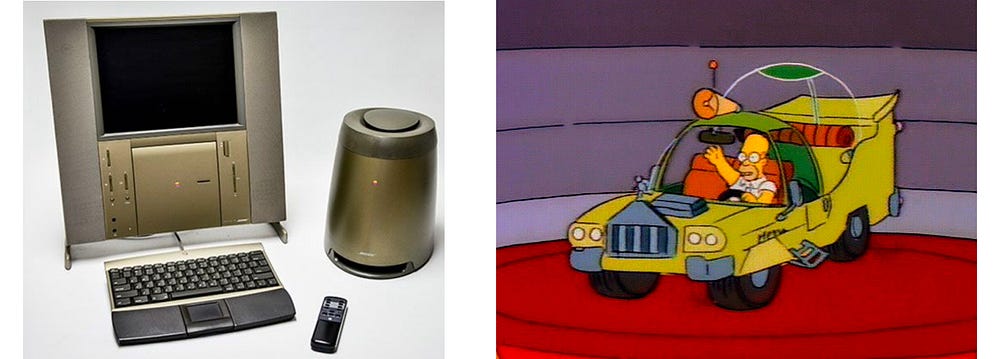

failed products. Remember the 20th Anniversary Mac?

Yeah, I thought not. One of the reasons I can’t forget it is that I

think of it every time they show that episode of The Simpsons where

Homer designs a car.

Even in the Jobs era, there were some product design howlers, including the notoriously unusable “hockey puck” Apple Mouse that was released in 1998. Then, of course, there were the first-generation plastic MacBooks that first discoloured and then (literally) fell to pieces, earning themselves the nickname of “Crackbooks” in the process.

Dumb

decisions in the Cook era have included a mouse that you have to turn

upside-down to charge, and a battery pack for your iPhone that looks

like a parody product, as well as making your phone look pregnant.

Until

recently, it was possible to take these eccentricities in good humor,

largely because they were not that important. But things have been

getting more serious in the past year.

For

a start, Apple has embraced its market position and begun to

systematically position its products as exclusive, premium alternatives

to its run-of-the-mill competitors. This has included significant price

hikes for its flagship products. A top-of-the-range MacBook Pro will set

you back well over $4,000 with a 2TB hard drive, and the iPhone X

begins at $999.

As

a strategy, this might have been fine, had it not coincided with a

series of increasingly embarrassing product design blunders. The 2016

and 2017 MacBook Pro have widely-reported problems with creaking or cracking

screen hinges, and failing keyboards. Add to that some bizarre design

decisions — such as adding a largely useless Touch Bar and a comically

oversized trackpad — and you start to wonder what is going on.

The

most widely remarked-upon oddity of the iPhone X is the “notch”, though

I doubt that’s going to be an enduring objection to the product; it may

indeed prove to be a very useful piece of branding at a time when other

“all-screen” smartphones are pretty much indistinguishable from one

another.

More likely to hit the iPhone X’s reputation are emerging security problems with FaceID, which, combined with the product’s exceptionally high price, may go some way to explaining the reportedly slow sales of the handset and its rumoured discontinuation.

In short, Apple has set itself up as being better than the rest,

but has got into a bad habit of releasing products — both hardware and

software — that can’t really support that claim, especially given that

the quality of PC and Android products have increased markedly over the

past 5 years.

In

just the past few weeks, this mismatch between the company’s

positioning, and what it is tending to deliver, was painfully evident in

the disastrous flaws that MacOS High Sierra shipped with. One bug even

allowed anyone to log in to any Mac as an administrator without a password,

which led Apple to issue an emergency fix and a grovelling apology.

Such a basic error would be inexcusable in a bargain-basement product;

that it happened in a major release of MacOS is astonishing from a

company that has set itself up as a paragon of virtue in its industry.

Which

leads us to our prediction. It’s within Apple’s power to turn things

around this year, but it’s going to be difficult. Some of these issues

are probably evidence of failing processes within the company — for

example, inadequate pre-release quality control and software

testing — while the loss of genuinely “pro” features in the MacBook Pro

in favor of expensive adapters and gimmicks like the Touch Bar show a

lack of connection with user needs.

In

2018, if Apple wants to preserve its prime industry position and

justify its price tags, it needs to return to real user-centered product

design and re-focus on truly exceptional product execution. What’s more

likely to happen, we fear, is that we will see another couple of

botched product releases and embarrassing security problems,

precipitating an identity crisis and maybe even some high-level

departures from the company following 4 years of flat-lining revenue growth.

2. First-wave social media will start to decline

For

the purposes of this article, we’re defining “first-wave” social media

as Facebook and Twitter — though of course before that, there was the

social media vanguard of MySpace, Bebo, and FriendsReunited.

If,

like me, you have spent (too) much of the past decade reluctantly but

compulsively attached to social media, you might find it hard to believe

that Facebook or Twitter will ever die. But, of course, nothing lasts

forever, and there are signs that these services are past their prime.

They

were most popular amongst millennials, who hit adulthood in the

mid-2000s and were excited by the prospect of an easy way to keep in

touch with their nascent networks of friends and professional contacts.

Facebook also offered an important, accessible way for older people to

connect with friends and family far away.

A younger generation of post-millennials, though, have largely failed to see the attraction

in these platforms, which offer the user very little granularity in how

they relate to and share with different people. Generation Z have

turned in their droves to Snapchat and encrypted services like WhatsApp for more secure and granular social networking — which can more faithfully mirror offline social relationships — and to Instagram

for a more narrowly defined public sharing experience. Post-millennials

have only ever known a data-driven, digital world, and easily see

through “meaningless” Facebook friendships.

Facebook has made attempts to recapture the teenage and young adult market with apps like 2014’s Lifestage.

This, however, was shut down last year following a lack of user uptake.

They have also tried to bring in younger users by acquiring Instagram

and other services that the demographic already use. More recently, Facebook acquired tbh, an anonymous compliments app for teens that was reportedly feared to be a potential commercial threat.

On

top of this, we have a growing and diverse chorus of voices warning of

the dangers of highly engineered social media services. These concerns

have emerged partly in response to the alleged propagation of fake and

planted news stories through social platforms during the 2016 US

election. However, it runs deeper than that.

More

importantly, critics draw attention to the fact that it is a core part

of the design of first-wave social media platforms to create cognitive

overload, psychological addiction, and compulsive sharing. It’s become

common knowledge that many high-profile figures in the tech world limit their kids’ screen time or even send them to screen-free schools, perhaps to combat the expansion of tech into every realm of life.

At the Davos international trade summit a few days ago, billionaire George Soros had this to say:

“Mining and oil companies exploit the physical environment; social media companies exploit the social environment. This is particularly nefarious because social media companies influence how people think and behave without them even being aware of it. This has far-reaching adverse consequences on the functioning of democracy, particularly on the integrity of elections.”

Similarly, at the end of last year, Chamath Palihapitiya, a former Facebook executive for growth until he left in 2011, expressed regret at his role in the company’s expansion:

“the short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works. No civil discourse, no cooperation, misinformation, mistruth. […] This is not about Russian ads. This is a global problem. It is eroding the core foundations of how people behave by and between each other.”

And

that’s not to mention the huge amounts of compromising personal data

that users give over, unpaid, to multi-billion dollar companies to feed a

lucrative advertising machine. Even The Economist — generally

far from being a radical voice — is asking whether users should be paid

for the data they currently freely surrender.

Our prediction is that 2018 will be a tipping point, as users become more aware of how corrosive first-wave social media

platforms have become. To maintain their market position, Facebook and

Twitter will need to go back to UX design basics and figure out afresh

what 2018’s users actually want and need from a social app.

In

the year ahead we are likely, at least, to see pushback against

first-wave social media’s exhibitionist tendency. User preferences will

shift towards more lo-fi, quasi-SMS interactions that require active

participation rather than passive scrolling. Particularly in a world

with an increasingly mobile workforce, business platforms such as Slack could provide a model for the future of social networking.

One

important change in the decade since these platforms emerged is that

users are now much more willing to pay for apps; paid subscriptions to

Spotify and Netflix, which would once have been scandalous to the

average web user, are now entirely normal.

User

bases, even huge ones, can be fickle: once the time comes, or perhaps

more importantly once the right new platform comes, we could see a

brutal, mass exodus of regular users within a few years, towards paid

platforms that deliver a more user-centered product.

3. Privacy and security will become more important user goals

Which

leads us to our final prediction: in 2018, privacy and security will

ratchet up the hierarchy of goals for many users. In the year ahead, experts deem it likely

that there will be further international cyber-attacks in the wake of

the WannaCry ransomware attack, which affected National Health Service

(NHS) computer systems in the UK, leading to the closure of some

services and diversion of ambulances. In turn, one of the reasons the

ransomware propagated quickly was a failure to apply existing Windows 7 security patches that closed the EternalBlue exploit of a Windows vulnerability.

In a press release last year, David Dufour, vice president of engineering and cybersecurity at Webroot, stated that

“This past year was unlike anything we’ve ever seen. Attacks such as NotPetya and WannaCry were hijacking computers worldwide and spreading new infections through tried-and-true methods. This list is further evidence that cybercriminals will continue to exploit the same vulnerabilities in increasingly malicious ways. Although headlines have helped educate users on the devastating effects of ransomware, businesses and consumers need to follow basic cybersecurity standards to protect themselves.”

Individual

users are beginning to wise up to the steps they can take to secure

their privacy, security and identity, and will soon start to demand more

of these controls from the devices and apps they use. To meet this

demand, companies are likely to step up their efforts in these areas,

perhaps accelerating programs to replace password systems or make 2-step

verification mandatory.

After all, there is a long way to go: less than 10% of Google users currently use 2-step verification.

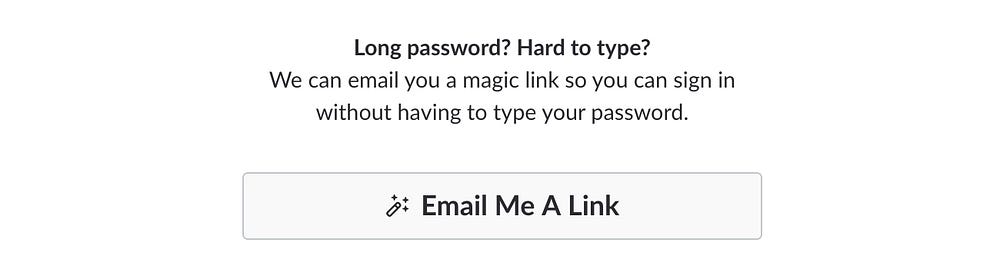

By the end of the year, we will see lots more screens like this one

from Slack, as more major sites and services beginning to retire

passwords completely in favour of other verification systems.

Growing

awareness of security and privacy risks may also accelerate the decline

of first-wave social media platforms, which are notoriously opaque when

it comes to how they use personal data, and the steps that users can

take to get it deleted.

In

part, this has been a failure of national and international governance

and regulation. Particularly with the introduction of significant legal

measures such as the EU Data Protection Regulation,

we will also see legislators adopting a less hands-off approach to tech

companies’ use of data; in the year ahead legislative bodies around the

world are likely to pass new laws demanding more rigorous data

standards and greater user control.

No comments:

Write comments