I’m

leading a VR development studio, but the truth is I’ve been navigating a

series of epic career learning curves that have taken me far outside of

my comfort zone, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

On my quest to

start sharing more about our process and lessons learned on the virtual

frontier, I thought I’d start with a bit of background on how I arrived

here in the first place.

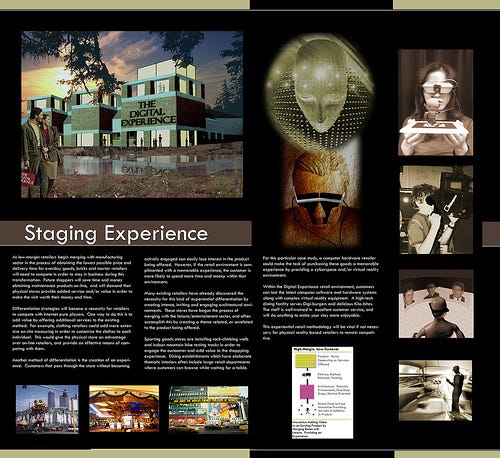

I

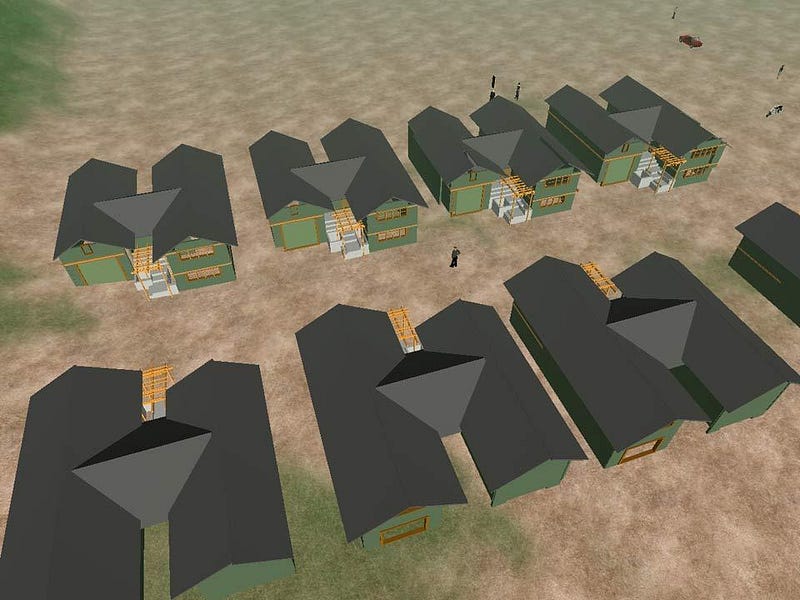

studied and practiced architecture, but I’ve been fascinated with

virtual technologies as far back as I can remember. In fact, my

architectural thesis project in grad school (image above) focused on how

VR and digital technologies would someday revolutionize

architecture — specifically retail architecture. This was 17 years ago,

when VR was very expensive, and largely inaccessible, but the brilliant

pioneers at work innovating in this field were demonstrating the massive

potential. It was only a matter of time before VR would find a way to

mainstream.

Like

so many other physical manifestations, from music to books and beyond, I

believe buildings are subject to a similar digital transcendence. It’s

already happening in a pretty big way, and this is just the beginning of

a major architectural transformation that might take another decade or

two to fully surface, but I digress… I’m saving this interest for a

future pivot, and almost certainly another epic learning curve to go

with it.

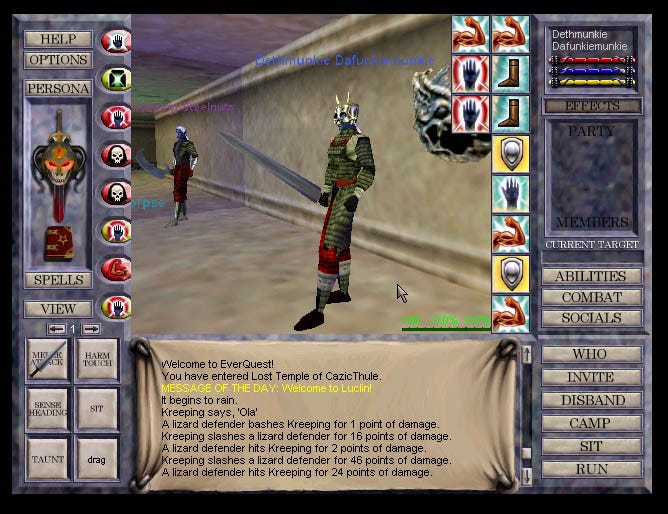

I tried using Everquest to visualize architecture.

I

had a level 47 Dark Elf Shadow Knight in Everquest, but spent most of

my time wandering around, exploring the environments. What I really

wanted to do was import my own architectural models to explore them

inside the game.

If

they could have such elaborate dungeons and forts to explore in

Everquest, with people from all around the world working together in the

game virtually, why couldn’t the same technology also be used to

visualize a new construction project, with the architect, building

owner, and construction team exploring or collaborating on the design

together?

This

quest to visualize architecture in a real-time world became a ‘first

principle’ in my career path that I’ve been chasing ever since.

I

met my amazing and tremendously patient wife, Kandy, in grad school,

and after studying architecture together in Europe and graduating, we

practiced architecture for some time before starting our own firm, Crescendo Design, focused on eco-friendly, sustainable design principles.

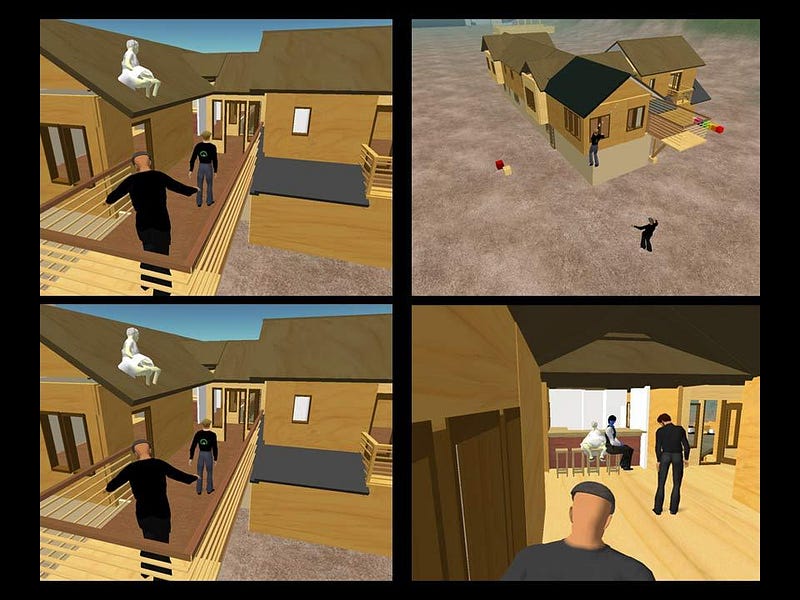

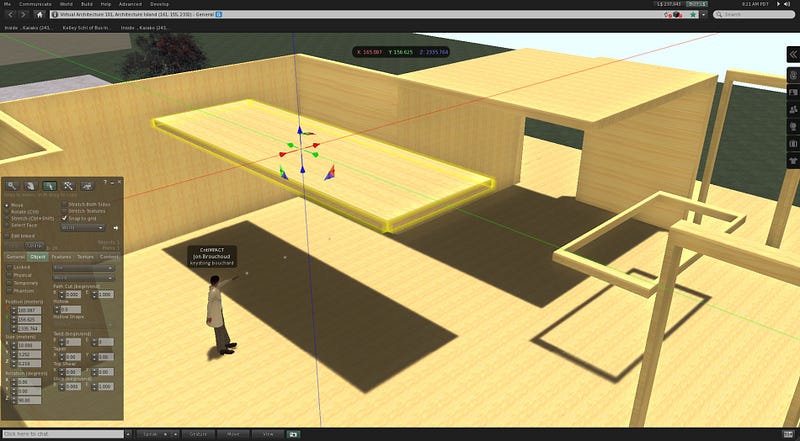

Then

one day in 2006, I read an article in Wired about Second Life — a

massively multi-player world where users could create their own content.

Within an hour, I was creating a virtual replica of a design we had on

the boards at the time. I had to use the in-world ‘prims’ to build it,

but I managed.

I

was working in a public sandbox at the time, and when I had the design

mostly finished, I invited the client in to explore it. They had 2 young

kids, who were getting a huge kick out of this watching over their

parent’s shoulders as they walked through what could soon be their new

home.

The Naked Lady, the Sheriff Bunny, and Epic Learning Curve #1.

We

walked in the front door, when suddenly a naked woman showed up and

started blocking the doorways. I reported her to the ‘Linden’

management, and a little white bunny with a big gold sheriff’s badge

showed up and kicked her out. “Anything else I can help with?” Poof..

the bunny vanished and we continued our tour. That’s when I realized I

needed my own virtual island (and what an odd place Second Life was).

But then something amazing happened that literally changed my career path, again.

I

left one of my houses in that public sandbox overnight. When I woke up

in the morning and logged in, someone had duplicated the house to create

an entire neighborhood — and they were still there working on it.

Architectural Collaboration on Virtual Steroids

I

walked my avatar, Keystone Bouchard, into one of the houses and found a

group of people speaking a foreign language (I think it was Dutch?)

designing the kitchen. They had the entire house decorated beautifully.

One

of the other houses had been modified by a guy from Germany who thought

the house needed a bigger living room. He was still working on it when I

arrived, and while he wasn’t trained in architecture, he talked very

intelligently about his design thinking and how he resolved the new roof

lines.

I

was completely blown away. This was architectural collaboration on

virtual steroids, and opened the door to another of the ‘first

principle’ vision quests I’m still chasing. Multi-player architectural

collaboration in a real-time virtual world is powerful stuff.

One

day Steve Nelson’s avatar, Kiwini Oe, visited my Architecture Island in

Second Life and offered me a dream job designing virtual content at his

agency, Clear Ink, in Berkeley, California. Kandy and I decided to

relocate there from Wisconsin, where I enjoyed the opportunity to build

virtual projects for Autodesk, the U.S. House of Representatives, Sun

Microsystems and lots of other virtual installations. I consider that

time to be one of the most exciting in my career, and it opened my eyes

to the potential for enterprise applications for virtual worlds.

Wikitecture

I

started holding architectural collaboration experiments on Architecture

Island. We called it ‘Wikitecture.’ My good friend, Ryan Schultz, from

architecture school suggested we organize the design process into a

branching ‘tree’ to help us collaborate more effectively.

Studio

Wikitecture was born, and we went on to develop the ‘Wiki Tree’ and one

of our projects won the Founder’s Award and third place overall from

over 500 entries worldwide in an international architecture competition

to design a health clinic in Nyany, Nepal.

These

were exciting times, but we were constantly faced with the challenge

that we weren’t Second Life’s target audience. This was a

consumer-oriented platform, and Linden Lab was resolutely and

justifiably focused on growing their virtual land sales and in-world

economy, not building niche-market tools to help architects collaborate.

I don’t blame them — more than 10 years after it launched, it still has

a larger in-world economy of transactions of real money than some small

countries.

We

witnessed something truly extraordinary there — something I haven’t

seen or felt since. Suffice it to say, almost everything I’ve done in

the years since have been toward my ultimate goal of someday, some way,

somehow, instigating the conditions that gave rise to such incredible

possibilities. We were onto something big.

No comments:

Write comments