How to Design Social Systems (Without Causing Depression and War)

Here

I’ll present a way to think about social systems, meaningful

interactions, and human values that brings these often-hazy concepts

into focus. It’s also, in a sense, an essay on human nature. It’s

organized in three sections:

- Reflection and Experimentation. How do people decide which values to bring to a situation?

- Practice Spaces. Can we look at social systems and see which values they support and which they undermine?

- Sharing Wisdom. What are the meaningful conversations that we, as a culture, are starved for?

I’ll

introduce these concepts and their implications for design. I will show

how, applied to social media, they address issues like election

manipulation, fake news, internet addiction, teen depression &

suicide, and various threats to children. At the end of the post, I’ll

discuss the challenges of doing this type of design at Facebook and in

other technology teams.

Reflection and Experimentation

As I tried to make clear in my letter, meaningful interactions and time well spent are a matter of values.

For each person, certain kinds of acts are meaningful, and certain ways

of relating. Unless the software supports those acts and ways of

relating, there will be a loss of meaning.

In the section below about practice spaces,

I’ll cover how to design software that’s supportive in this way. But

first, let’s talk about how people pick their values in the first place.

We often don’t know how we want to act, or relate, in a particular situation. Not immediately, at least.

When

we approach an event (a conversation, a meeting, a morning, a task),

there’s a process — mostly unconscious — by which we decide how we want

to be.

Interrupting

this can lead to doing things we regret. As we’ll see, it can lead to

internet addiction, to bullying and trolling, and to the problems teens

are having online.

So, we need to sort out the values with which we want to approach a situation. This is a process. I believe it’s the same process, whether you’re deciding something small — like how openly you will approach a particular conversation — or something big.

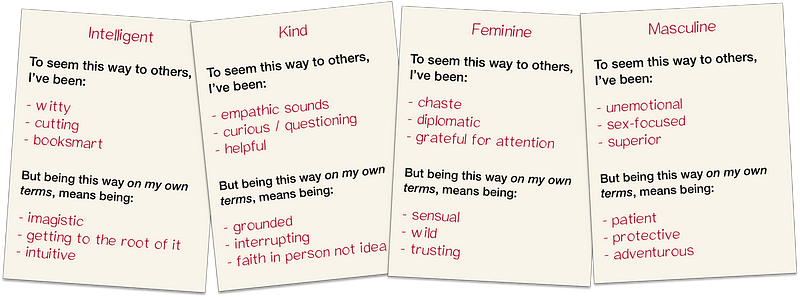

Let’s start with something big: many teenagers are engaged in sorting out their identities: they take ideas about how they ought

to act (manly, feminine, polite, etc) and make up their own minds about

whether to approach situations with these values in mind.

For

these teens, settling on the right values takes a mix of

experimentation and reflection. They need to try out different ways of

being manly, feminine, intelligent, or kind in different situations and see how they work. They also need to reflect on who they want to be and how they want to live.

These

two ingredients — experimentation and reflection — are required to sort

out our values. Even the small decisions (for example, deciding how to

balance honesty and tact in a conversation) require experimenting in real situations, and reflecting on what matters most.

This process can be intuitive, nonverbal, and unconscious, but it is vital.¹

If we don’t find the right values, it’s hard to feel good about what we

do. The following circumstances interfere with experimentation and

reflection:

- High stakes. When deviation from norms becomes disastrous in some way — for instance, with very high reputational stakes — people are afraid to experiment. People need space to make mistakes and systems and social scenes with high consequences interfere with this.

- Low agency. To put values to the test, a person needs discretion over the manner of their work: they need to experiment with moral values, aesthetic values, and other guiding ideas. Some environments — many of them corporate — make no room for being guided by one’s own moral or aesthetic ideas.

- Disconnection. One way we judge the values we’re experimenting with is via exposure to their consequences. We all need to know how others feel when we treat them one way or another, to help us decide how we want to treat them. Similarly, an architect needs to know what it’s like to live in the buildings she designs. When the consequences of our actions are hidden, we can’t sort out what’s important.²

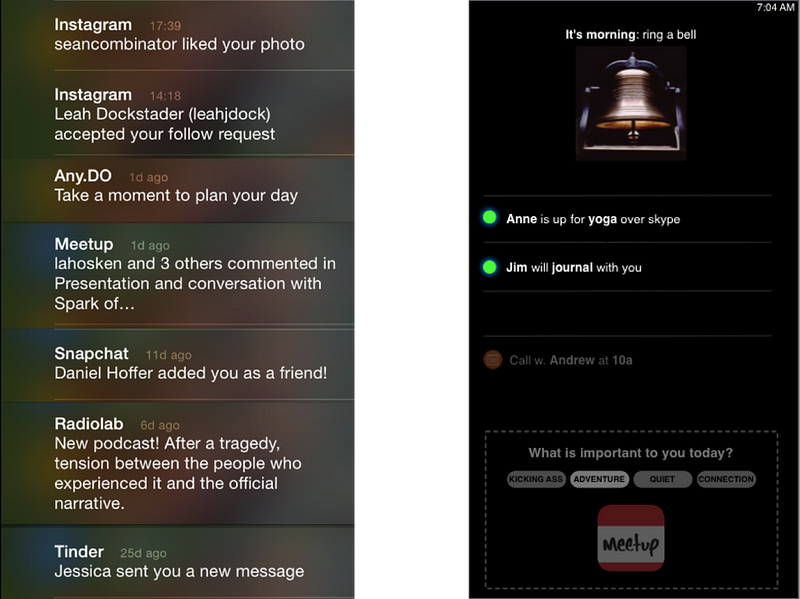

- Distraction and overwork. We also lose the capacity to sort out our values when reflection becomes impossible. This is the major cost of noisy environments, infinite entertainment, push notifications, and some types of poverty.

- Lack of faith in reflection. Finally, people can come to consider reflection to be useless — or to be avoided — even though it is so natural. The emotions which trigger reflection, including doubt and confusion, can be brushed away as distractions. One way this happens, is if people view their choices through a behaviorist lens: as determined by habits, reinforcement learning, or permanent drives.³ This makes it seem like people don’t have values at all, only habits, tastes, and goals. Experimentation and reflection seem useless.

Software-based social spaces can be disastrous for experimentation and reflection.

One

reason that private group messaging (like WhatsApp and Messenger) is

replacing virality-based forums (like Twitter, News Feed, and

increasingly, Stories) is that the latter are horrible for experimenting

with who we are. The stakes are too high. They seem especially bad for

women, for teens, and for celebrities—which may partly explain the rise

in teen suicide—but they're bad for all of us.

A

related problem is online bullying, trolling, and political outrage.

Many bullies and trolls would embrace other values if they had a chance

to reflect and were better exposed to consequences. In-person spaces are

much better for this.

Reflection can be encouraged or discouraged by design — this much is clear from the variety of internet-use helpers, like Moment and Intent. All of us (not just bullies and trolls) would use the Internet differently if we had more room for reflection.

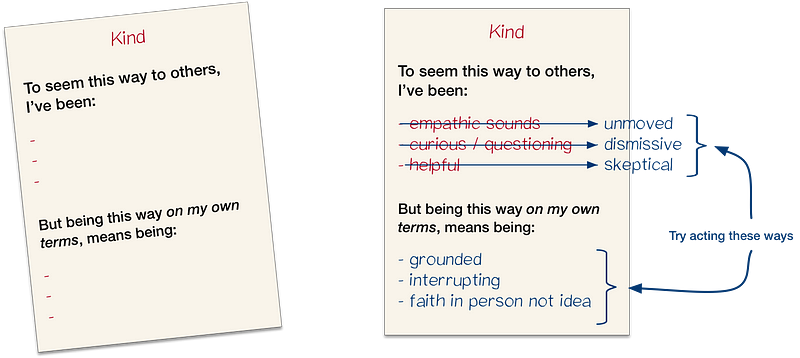

Exercise: On My Own Terms

In order to learn to support users in experimentation and reflection, designers must experiment and reflect on their own values. On My Own Terms is an exercise for this. Players fill out a worksheet, then socialize in an experimental way.

In

the experimentation part, players defy norms they’ve previously obeyed,

and see how it works out. Often they find that people like them better

when they are less conventional — even when they are rude!

Here’s

one thing this game makes clear: we discover what’s important to us in

the context of real choices and their consequences. People often think

they have certain values (eating kale, recycling, supporting the

troops) but when they experiment and reflect on real choices, these

values are discarded. They thought they believed in them, but only out

of context.

This is how it was for me with consistency, rationality, masculinity, and being understated. When I played On My Own Terms, I decided to value these less.⁴ My true values are only clear through experimentation and reflection.

For

users to have meaningful interactions and feel their time was well

spent, they need to approach situations in a way they believe in. They

need space to experiment and reflect.

But this is not enough.

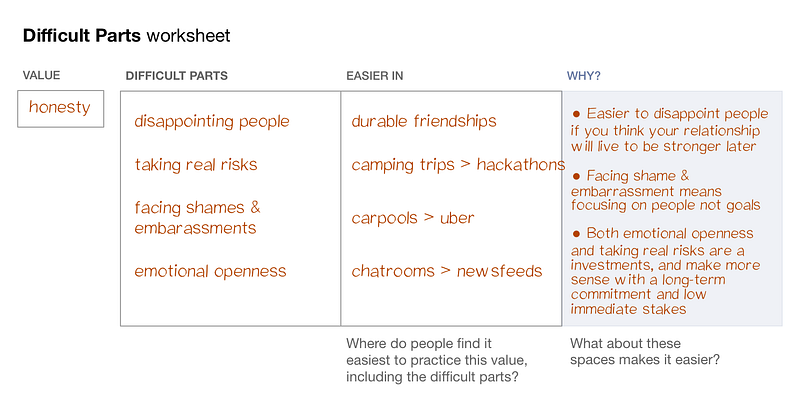

Practice Spaces

Every

social system makes some values easier to practice, and other values

harder. Even with our values in order, a social environment can

undermine our plans.

Most social platforms are designed in a way that encourages us to act against our values: less humbly, less honestly, less thoughtfully,

and so on. Using these platforms while sticking to our values would

mean constantly fighting their design. Unless we’re prepared for a

fight, we’ll likely regret our choices.

There’s a way to address this, but it requires a radical change in how we design: we must reimagine social systems as practice spaces for the users’ values — as virtual places custom built to make it easier for the user to relate and to act in accord with their values.

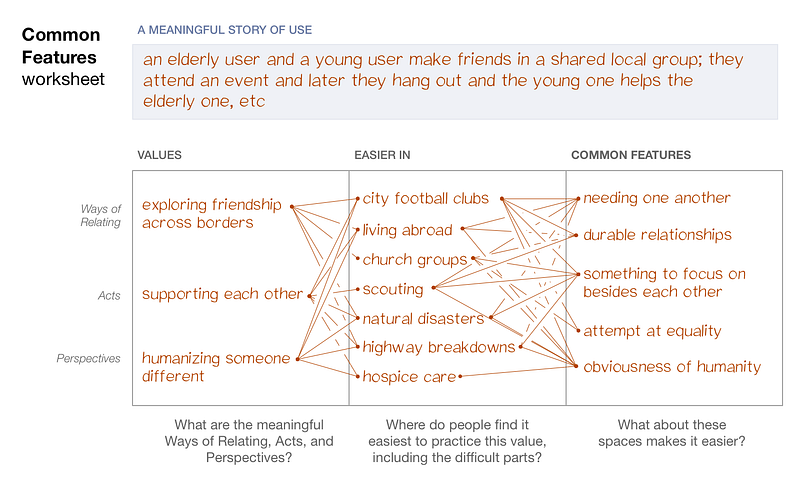

Designers must get curious about two things:

- When users want to relate according to a particular value, what is hard about doing that?

- What is it about some social spaces that can make relating in this way easier?

For example, if an Instagram⁵ user valued being creative, being honest, or connecting adventurously,

then designers would need to ask: what kinds of social environments

make it easier to be creative, to be honest, or to connect

adventurously? They could make a list of places where people find these

things easier: camping trips, open-mics, writing groups, and so on.

Next,

the designers would ask: which features of these environments make them

good at this? For instance, when someone is trying to be creative, do

mechanisms for showing relative status (like follower counts) help or

hurt? How about when someone wants to connect adventurously? Or, with

being creative, is this easier in a small group of close connections, or

a large group of distant ones? And so on.

To take another example, if a News Feed user believes in being open-minded,

designers would ask which social environments make this easier. Having

made such a list, they would look for common features. Perhaps it’s

easier to be open-minded when you remember something you respect about a

person’s previous views. Or, perhaps it’s easier when you can tell if

the person is in a thoughtful mood by reading their body language. Is

open-mindedness more natural when those speaking have to explicitly

yield time for others to respond? Designers would have to find out.⁶

Exercise: Space Jam

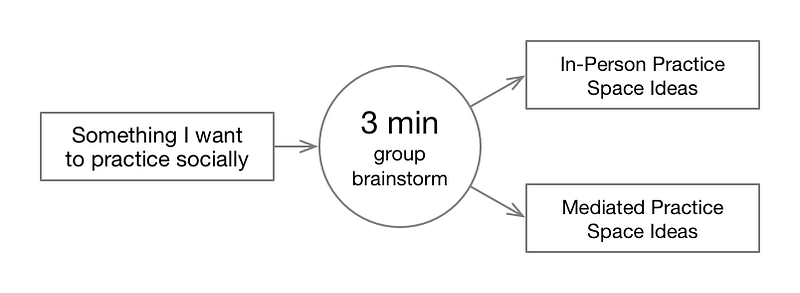

To start thinking this way, it’s best if designers focus first on values which they themselves have trouble practicing. In this game, Space Jam, each player shares something they’d like to practice, some way of interacting. Then everyone brainstorms, imagining practice spaces (both online and offline) which could make this easier.

Here’s an example of the game, played over Skype with three designers from Facebook:

Eva says she wants to practice “changing the subject when a conversation seems like a dead end.”

Someone comments that Facebook threads are especially bad at this. We set a timer for three minutes and brainstorm on our own. Then everyone presents one real-world way to practice, and one mediated way.

George’s idea involves a timer. When it rings, everyone says “this conversation doesn’t meet my need for ____”. Jennifer suggests something else: putting a bowl in the middle of a conversation. Player can write out alternate topics and put them in the bowl in a conspicuous but non-interrupting way. (Jennifer also applies this idea to Facebook comments, where the bowl is replaced by a sidebar.)

We all wonder together: could it ever be “okay” for people to say things like “this conversation doesn’t meet my need for ____”? Under what circumstances is this safe to say?

This leads to new ideas.

In the story above, Eva is an honest person. But that doesn’t mean it’s always easy

to be honest. She struggles to be honest when she wants to change the

conversation. By changing the social rules, we can make it easier for

her to live according to her values.

Games like Space Jam

show how much influence the rules of social spaces have over us, and

how easy it is for thoughtful design to change those rules. Designers

become more aware of the values around them and why they can be

difficult to practice. They feel more responsible for the spaces they

are creating. (Not just the spaces they make for users, but also in

daily interactions with their colleagues). This gives them a fresh

approach to design.

If

designers learn this skill, they can support the broad diversity of

users’ values. Then users will no longer have to fight the software to

practice their values.

Sharing Wisdom

I hope the previous ideas—reflection, experimentation, and practice spaces—have given a sense for how to support meaningful actions. Let’s turn to the question of meaningful information and meaningful conversation.

We are having a problem in this area, too.

Amidst

nonstop communication — a torrent of articles, videos, and

posts — there is still a kind of conversation that people are starved

for, because our platforms aren’t built for it.

When this type of conversation — which I’ll call sharing wisdom — is

missing, people feel that no one understands or cares about what’s

important to them. People feel their values are unheeded, unrecognized,

and impossible to rally around.

As

we’ll see, this situation is easy to exploit, and the media and fake

news ecosystems have taken advantage. By looking at how this

exploitation works, we can see how conversations become ideological and

polarized, and how elections are manipulated.

But first, what do I mean by sharing wisdom?

Social

conversation is often understood as telling stories, sharing feelings,

or getting advice. But each of these can be seen as a way to discover

values.

When we ask our friends for advice — if you look carefully — we aren’t often asking about what we should do. Instead, we’re asking them about what’s important in our situation. We’re asking for values which might be new to us. Humans constantly ask each other “what’s important?” — in a spouse, in a wine, in a programming language.

I’ll call this kind of conversation (both the questions and the answers) wisdom.

Wisdom, n. Information about another person’s hard-earned, personal values — what, through experimentation and reflection, they’ve come to believe is important for living.

Wisdom

is what’s exchanged when best friends discuss their relationships or

jobs, when we listen to stories told by grandmothers, church pastors,

startup advisors, and so on.

It comes in many forms: mentorship, texts, rituals, games. We seek it naturally, and in normal conditions it is abundant.

For

various reasons, the platforms are better for sharing other things

(links, recommendations, family news) than for asking each other what’s

important. So, on internet platforms, wisdom gets drowned out by other

forms of discourse:

- By ideology. Our personal values are easily eclipsed by ideological values (for instance, by values designed to promote business, a certain elite, or one side in a political fight). This is happening when posts about partisan politics make us lose track of our shared (or sharable) concerns, or when articles about productivity outpace our deeper life questions.

- By scientism. Sometimes “hard data” or pseudo-scientific “models” are used to justify things that would be more appropriately understood as values. For instance, when neuroscience research is used to justify a style of leadership, our discourse about values suffers.

- By bullshit. Many other kinds of social information can drown out wisdom. This includes various kinds of self-promotion; it includes celebrities giving advice for which they have no special experience; it includes news. Information that looks like wisdom can make it harder to locate actual, hard-earned wisdom.

For

all these reasons, talk about personal values tends to evaporate from

the social platforms, which is why people feel isolated. They don’t

sense that their personal values are being understood.

In

this state, it’s easy for sites like Breitbart, Huffington Post,

Buzzfeed, or even Russia Today to capitalize on our feeling of

disconnection. These networks leverage the difficulty of sharing wisdom,

and the ease of sharing links. They make a person feel like they are

sharing a personal value (like living in a rural town or supporting women), when actually they are sharing headlines that twist that value into a political and ideological tool.

Exercise: Value Sharing Circle

For designers to get clear about what wisdom sounds like, it can be helpful to have a value sharing circle.

Each person shares one value which they have lived up to on the day

they are playing, and one which they haven’t. Here’s a transcript from

one of these circles:

There are twelve of us, seated for dinner. We eat in silence for what feels like a long time. Then, someone begins to speak. It’s Otto. He says he works at a cemetery. At 6am this morning, they called him. They needed him to carry a coffin during a funeral service. No one else could do it. So, he went. Otto says he lived up to his values of showing up and being reliable. But — he says — he was distracted during the service. He’s not sure he did a good job. He worries about the people who were mourning, whether they noticed his missteps, whether his lack of presence made the ritual less perfect for them. So, he didn’t live up his values of supporting the sense of ritual and honoring the dead.

In

the course of such an evening, participants are exposed to values

they’ve never thought about. That night, other people spoke of their

attempts to be ready for adventure, be a vulnerable leader, and make parenthood an adventure.⁷

Playing

this makes the difference between true personal values and ideologies

very clear. Notice how different these values are from the values of

business. No one in the circle was particularly concerned with

productivity, efficiency, or socio-economic status. No one was even

concerned with happiness!

Social platforms could make it much easier to share our personal values (like small town living) directly, and to acknowledge one another and rally around them, without turning them into ideologies or articles.

This

would do more to heal politics and media than any “fake news”

initiative. To do it, designers will need to know what this kind of

conversation sounds like, how to encourage it, and how to avoid drowning

it out.

The Hardest Challenge

I’ve pointed out many challenges, but left out the big one. 😕

Only people with a particular mindset can do this type of design. It takes a new kind of empathy.

Empathy can mean understanding someone’s goals, or understanding someone’s feelings.⁸ And these are important.

But to build on these concepts — experimentation, reflection, wisdom, and practice spaces— a designer needs to see the experimental part of a person, the reflective part, the person’s desire for (and capacity for) wisdom, and what the person is practicing.⁹

As with other types of empathy, learning this means growing as a person.

Why?

Well, just as it’s hard to see others’ feelings when we repress our

own, or hard to listen to another person’s grand ambitions unless we are

comfortable with ours... it’s hard to get familiar with another

person’s values unless we are first cozy with our own, and with all the

conflicts we have about them.

This

is why the exercises I’ve listed (and others, which I didn’t have space

to include) are so important. Spreading this new kind of empathy is a

huge cultural challenge.

But it’s the only way forward for tech.

Thanks for reading. (Here are the credits and footnotes.)

Please clap for this and the previous post!

And…

- There is a community you can join to practice this stuff.

- Learn about a complimentary approach in metrics.

- Read more about human values, the connection between values and emotions, or the history of time well spent.

No comments:

Write comments