UI/UX Case Study: Mobile Self-Checkout App Design Concept

Fashion Retail and E-Commerce App Redesign

The

UI/UX case study documents the processes involved in a redesign of a

fashion retail and e-commerce app. The app includes a product scan

feature for customers to perform a self-checkout at a physical store.

This design sprint took 11-days to complete and is submitted to the UXDI

course at General Assembly, Singapore.

Project Brief

Work in a team to identify problems and/or opportunities with an existing mobile application and utilise your knowledge to design a solution.

For this project, my team selected the Uniqlo, Singapore app

to redesign. For this documentation, the brand name will not be

mentioned again below. The ideas below apply to most fashion retailers

with an e-commerce presence.

Overview

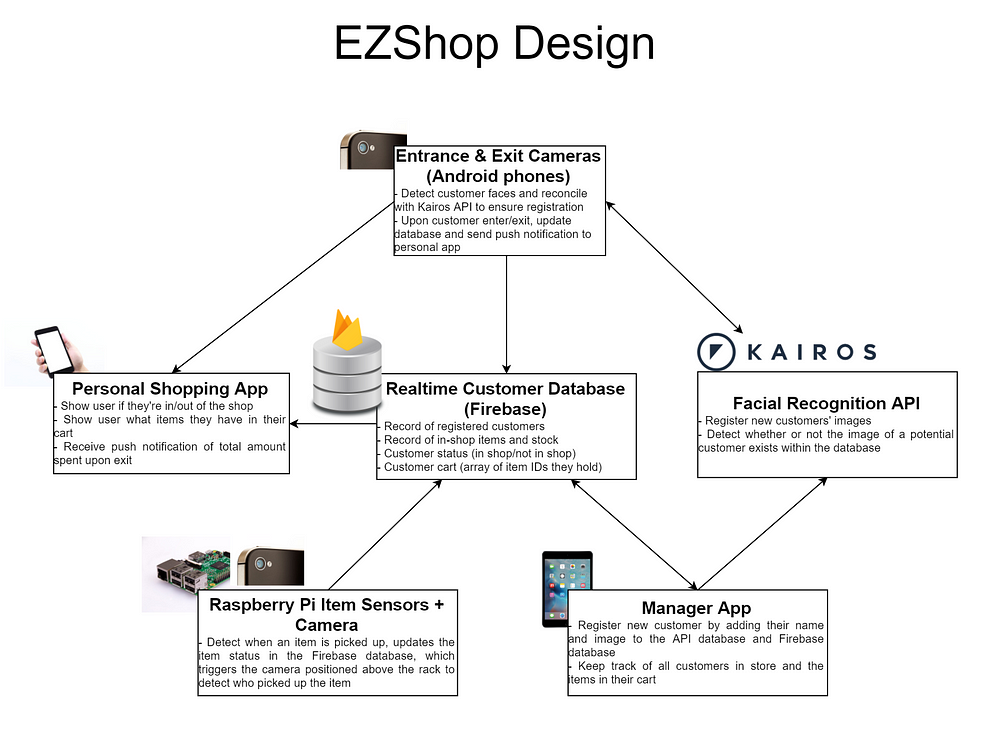

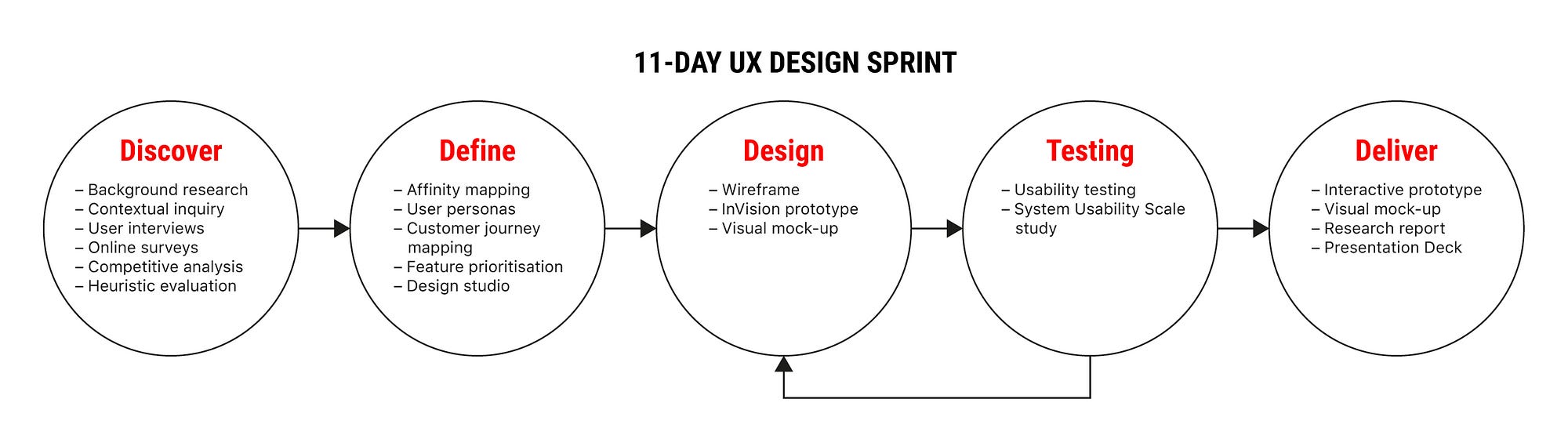

The 11-days group project (3 members) includes the following processes and methodologies:

#1 Discover

- Background research

- Contextual inquiry

- User Interviews

- Online surveys

- Competitive analysis

- Heuristic evaluation

#2 Define

- Affinity mapping

- User personas

- Customer journey mapping

- Feature prioritisation

- Design studio

#3 Design

- Wireframe

- InVision prototype

- Visual mock-up

#4 Testing

- Usability testing

- System Usability Scale study

#5 Deliver

- Interactive prototype

- Visual mock-up

- Research report

- Presentation

The Context — Competitive Retail Scene & Mobile Payment in Singapore

It is increasingly difficult for retail businesses to remain competitive in Singapore. This is due to the high rental fees to maintain a physical store and the difficulty in hiring lower-skilled sales assistants.

In addition, consumers are increasingly shopping online on platforms such as Taobao, ASOS, ZALORA for their fashion fix.

In the recent Singapore National Day Rally Speech (Aug 17), the prime minister pushes for consumers and retailers to adopt mobile payments. This will be done through initiatives such as ‘PayNow’ and a common national QR code.

Based on this setting, my team picked a retail outlet with a physical and online (mobile app) presence as our project.

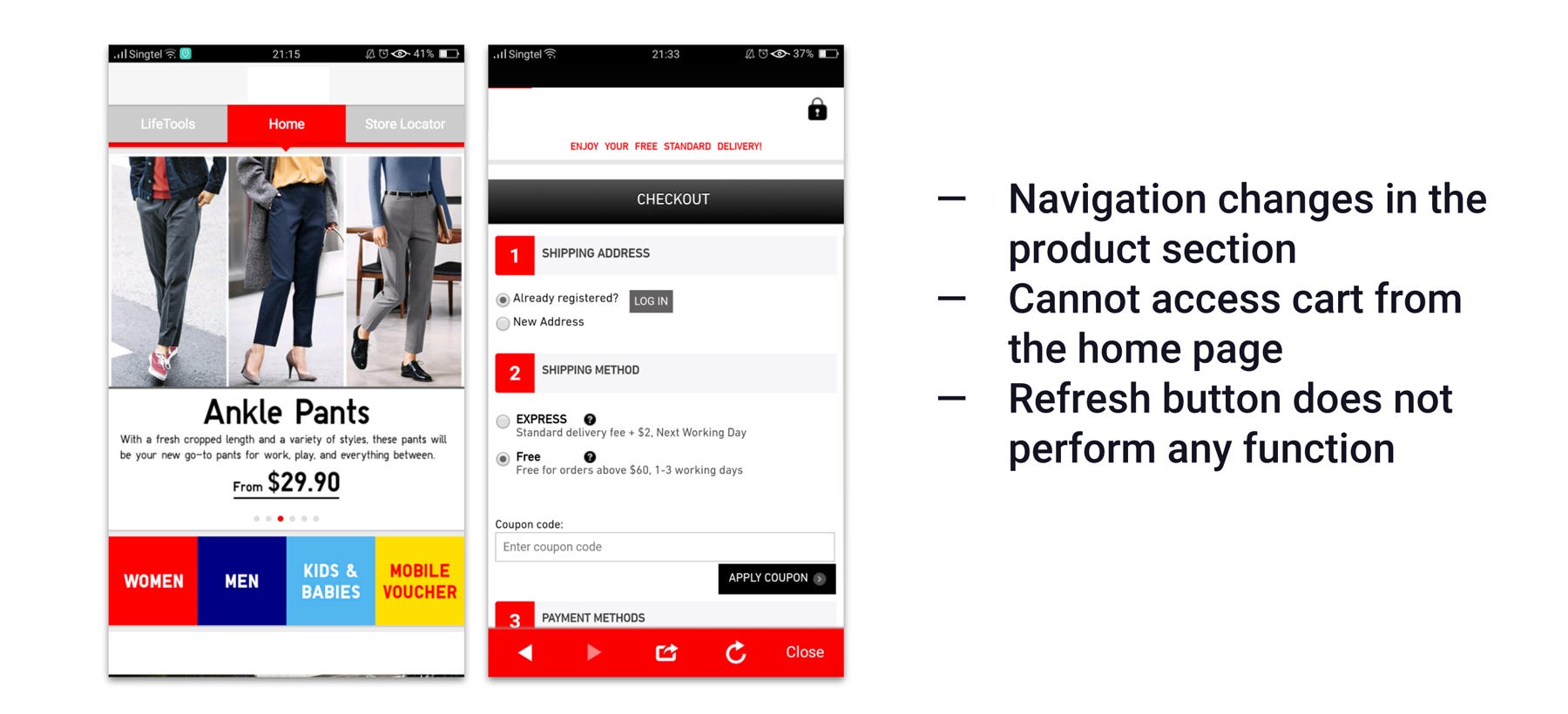

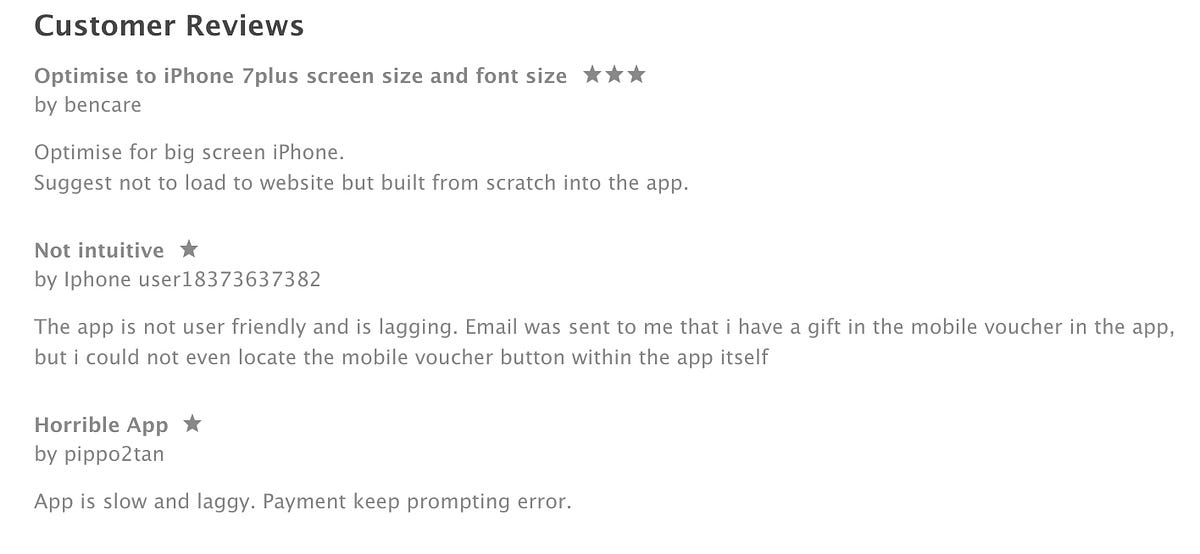

Heuristic Evaluation

First, we started by analysing the existing app to identify key problems and issues. This was compared to online reviews on Google Play and the App Store.

The main issues discovered was the app is a hybrid app, i.e. it is pulling information from a web page. This creates potential issues:

- Slow loading as most of the information is downloaded only when needed.

- The experience is not catered to mobile. Fonts, buttons, and images appear too small on the mobile phone.

- Navigation is inconsistent throughout the app.

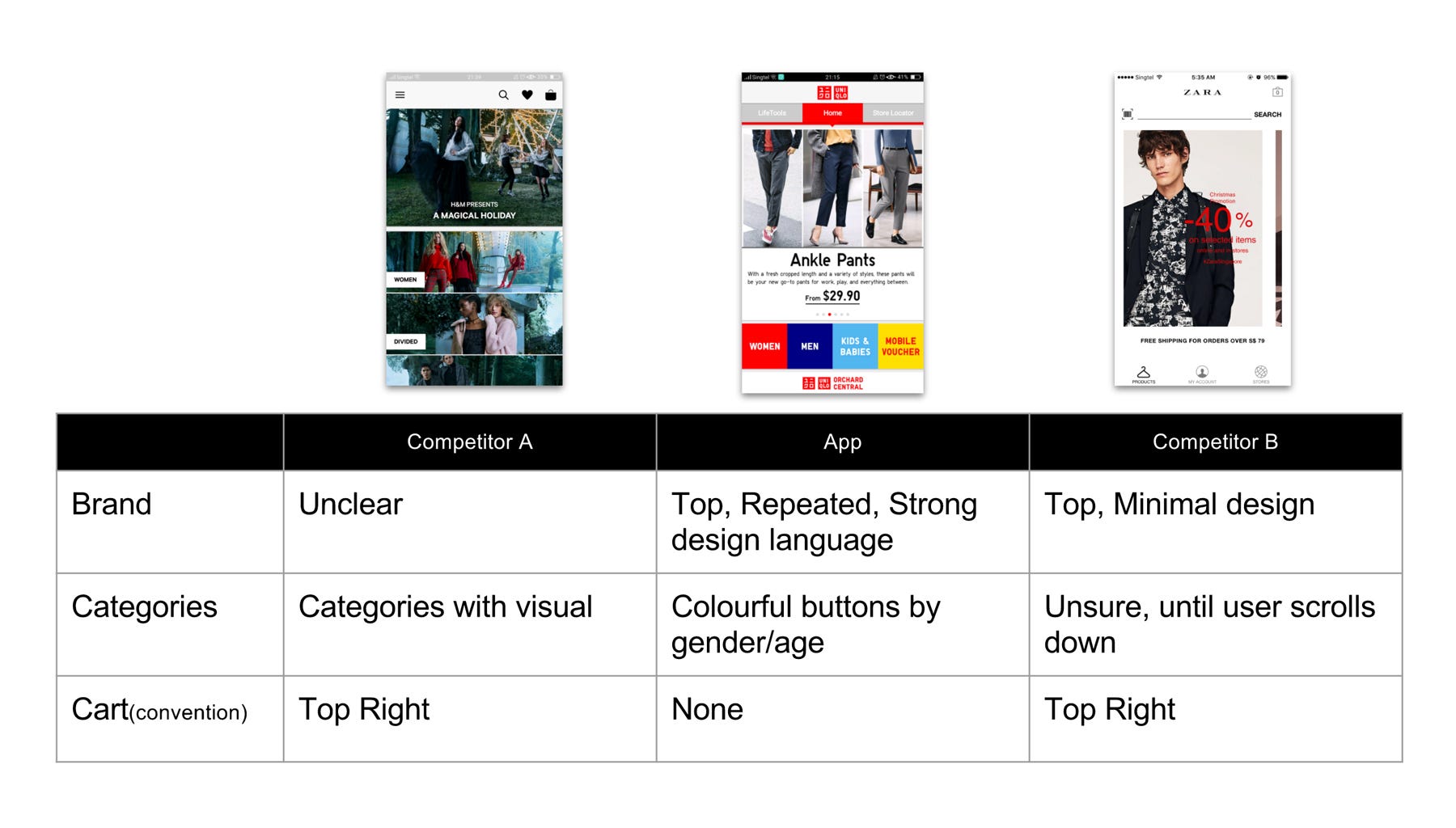

Competitive Analysis

Next, we compared the app to the competitors’ apps. The competitors are determined by these 4 points:

- Fashion retailers with a physical store in Singapore;

- Has an e-commerce mobile app;

- Similar price range and demographics;

- Fast-fashion retailer.

Key findings identified were:

- Most shoppers do not know of or use the apps;

- No in-store signages were found to encourage its usage;

- Competitors have a barcode scanner to provide additional product information. This feature integrates the in-store and mobile experience;

- Competitors have a significantly better app presentation as it feels less cluttered;

- App approaches may be different — one is more editorial, while the other is focused on e-commerce.

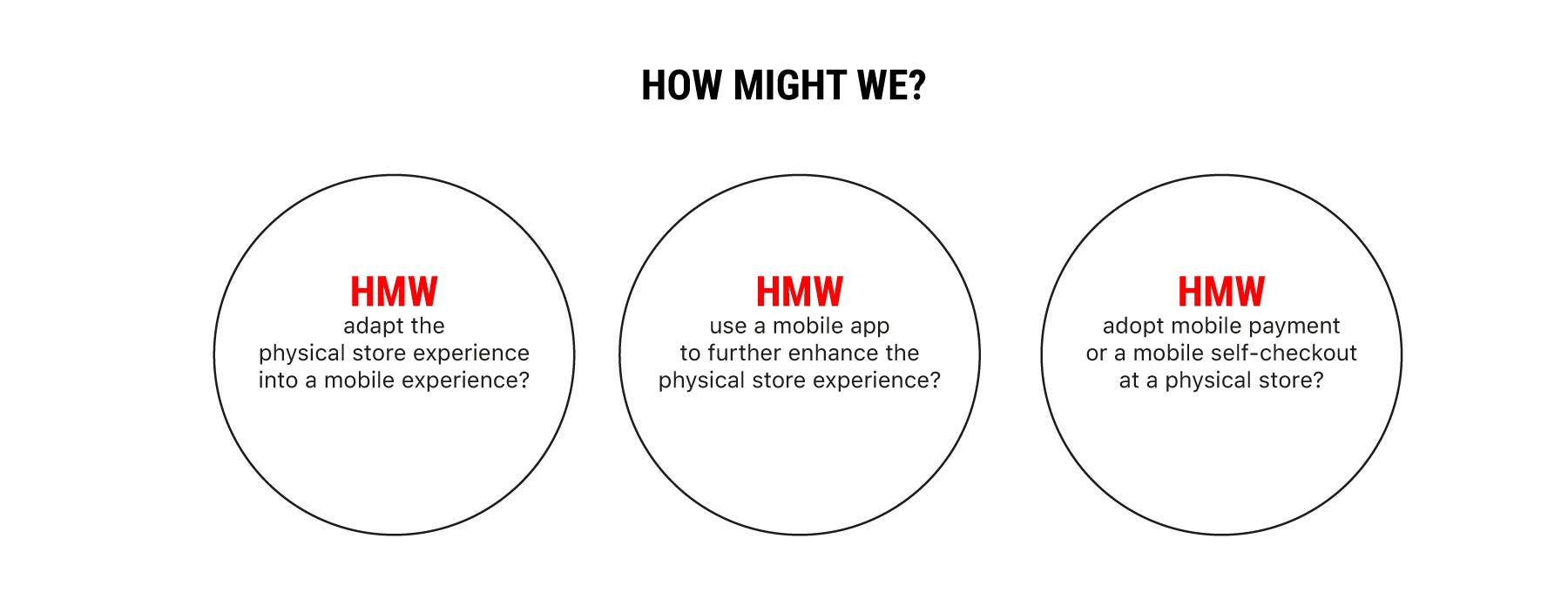

The Big Questions — How Might We…

At the start of the project, we had three main questions in mind.

How might we…

- adapt the physical store experience into a mobile experience?

- use a mobile app to further enhance the physical store experience?

- adopt mobile payment or a mobile self-checkout at a physical store?

Defining the In-store Experience

First, we define the unique experience at the physical store to adapt it to the mobile app.

- Greeted with ‘Welcome to (the store)’ every time you enter the shop;

- Same familiar shop layout at every outlet;

- Wide open aisle, bright lights, neatly stacked shelves;

- Sales and promotions throughout the year for different products each week;

- Easy to find the right sizes without help from a sales assistant;

- Strong visual branding from clothes tag to signages.

Contextual Inquiry/Field Study

We conducted a field study at an outlet by speaking to customers and shop assistants. Also, we showed the product scan feature found on our competitor’s mobile app.

What we noticed and found out:

- Shoppers do not know of the app even though they frequently shop at the store.

- The current app is for e-commerce only.

- Shoppers will consider shopping online after knowing of the app.

- Shoppers are wowed by the product scan feature as the technology is fascinating. The same technology is already available at a kiosk at the flagship store (in the city). Other smaller outlets (in the neighbourhoods) did not have this kiosk, probably due to space constraints.

- The same product might be cheaper in the app as there are mobile exclusive discounts. This, although they may incur additional delivery fees ($6 for spendings < $30).

- Various products are available only at the flagship store or on the mobile app.

- Long queues were observed at the store during peak hours.

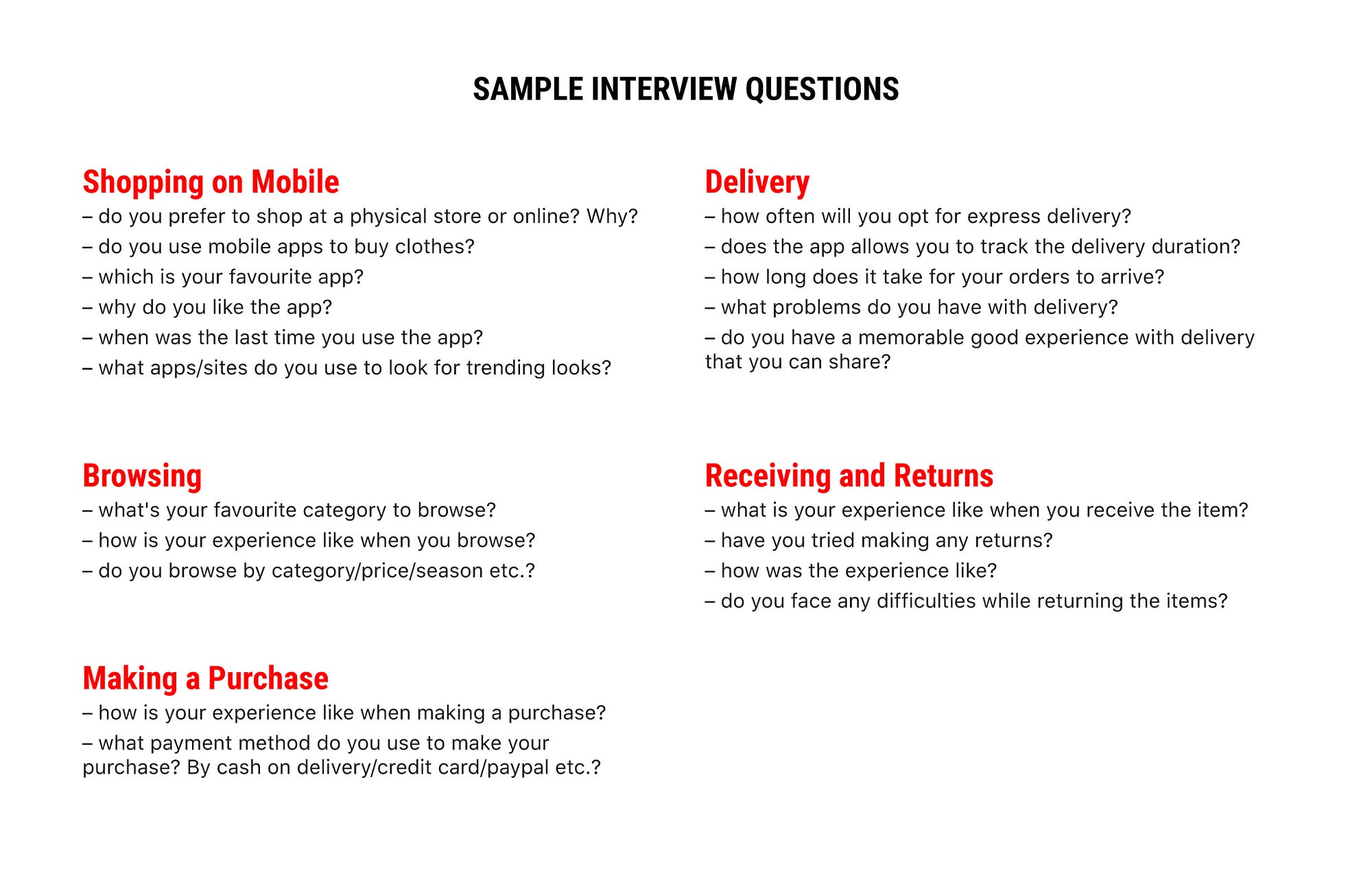

User Interviews

We

interviewed 7 users to find out what they think of the current app. The

questions we asked were centred on various touch points common to

fashion e-commerce apps. For example, we asked questions related to:

- browsing for clothes,

- making a purchase,

- waiting for the delivery,

- receiving the items,

- and making returns.

Key findings from the interviews:

- The app is easy to browse, hence there are no major issues with the navigation. The only issue is with ‘dresses’ being classified under ‘tops’.

- Frustration comes from the lack of filtering and a complicated check-out process.

- The app lacks clarity in the delivery options and fees.

- The app presentation is messy.

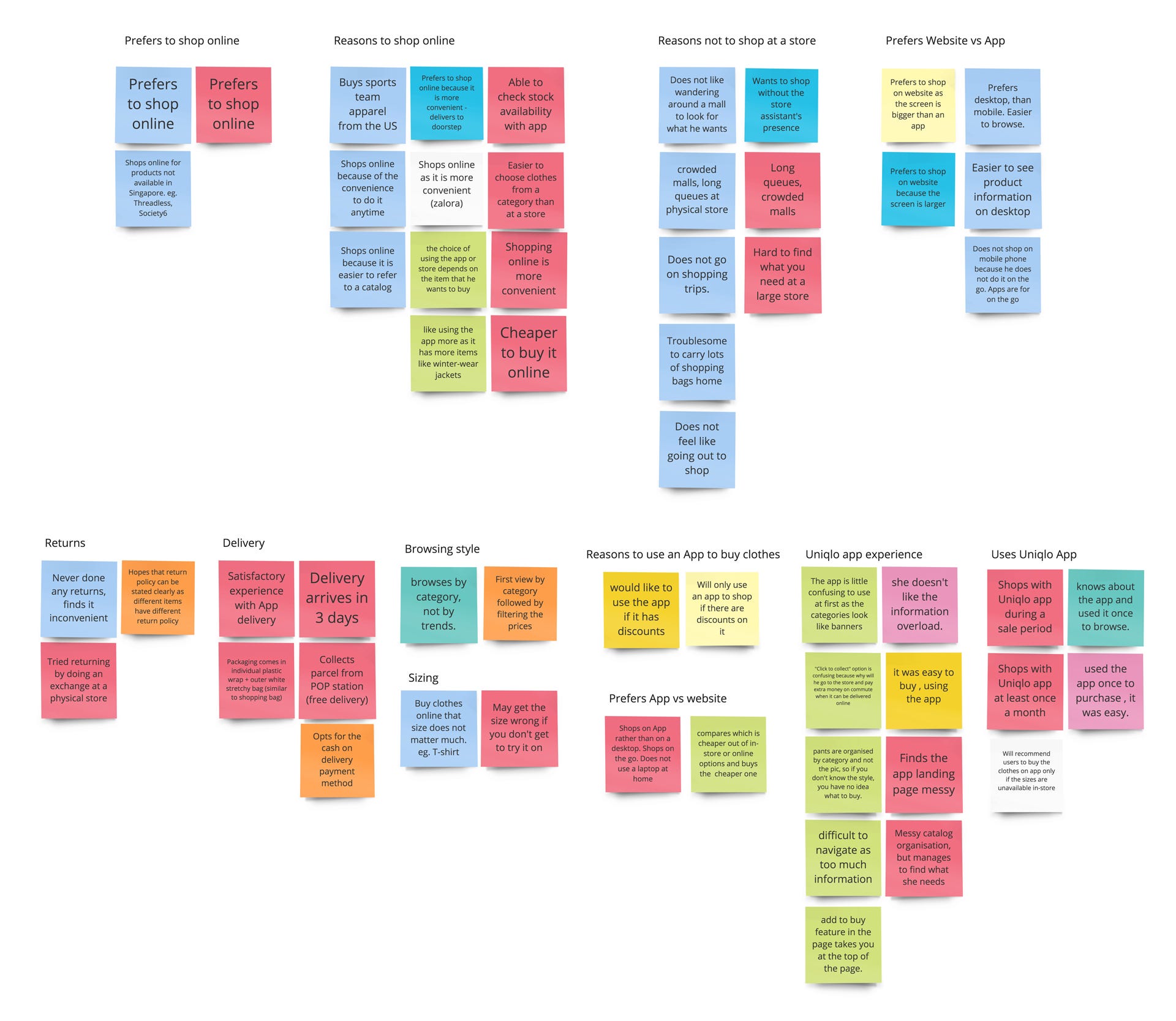

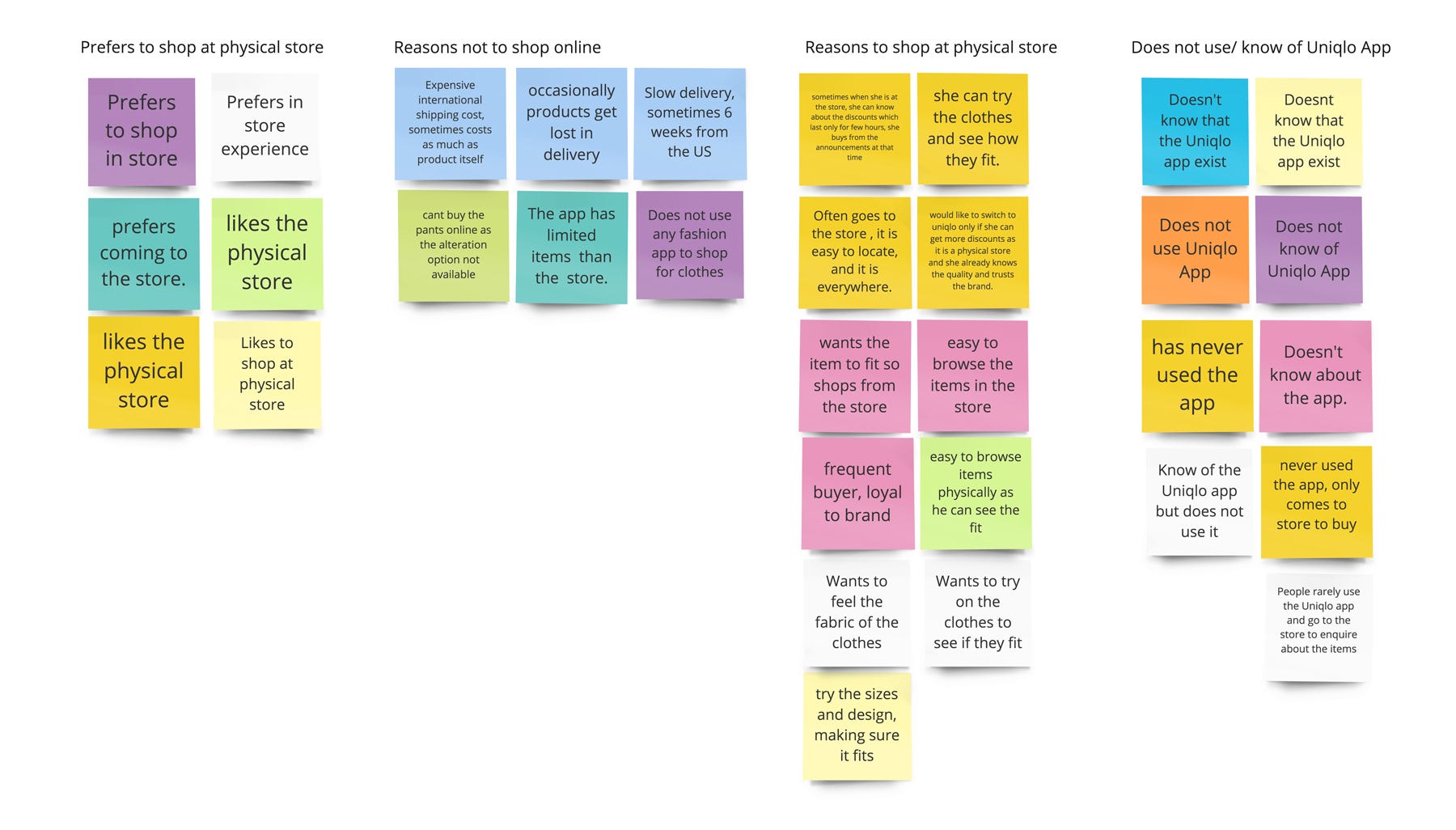

Affinity Mapping

After conducting user interviews and contextual inquiry, the next step we did was to organise the insights into groups

in an Affinity Map. With this map, we could identify common habits,

problems, and pain points. The map also helped us to identify 2 key

personas (elaborated below) where the same coloured post-its are usually grouped together. Eg. Red and pale blue posts-its are existing users.

User Personas and Customer Journey Map

Based

on the patterns identified in the affinity map, we came out with 2

personas — an existing user of the app, and a current shopper who is a

potential user of the app. These personas describe a typical

user/potential user, their habits, problems, pain points, and other

details about him/her.

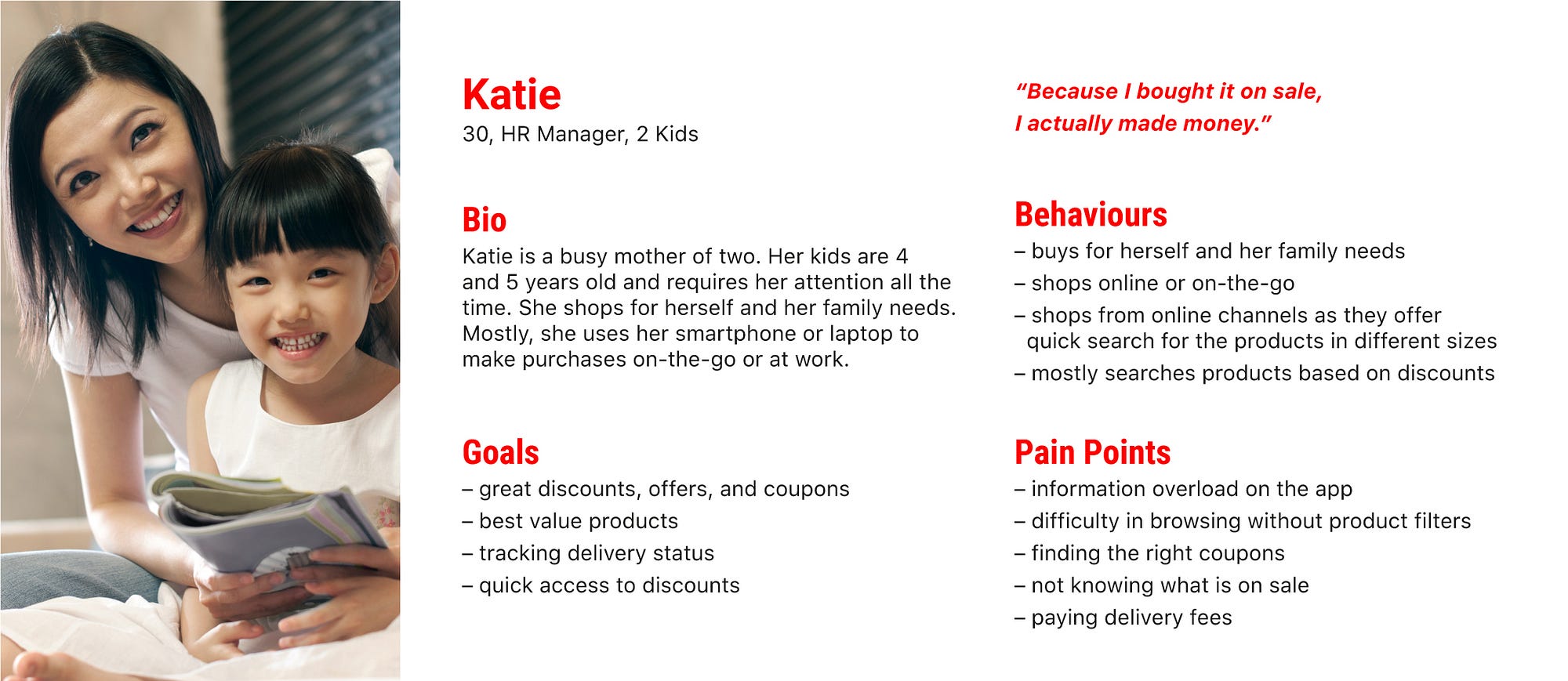

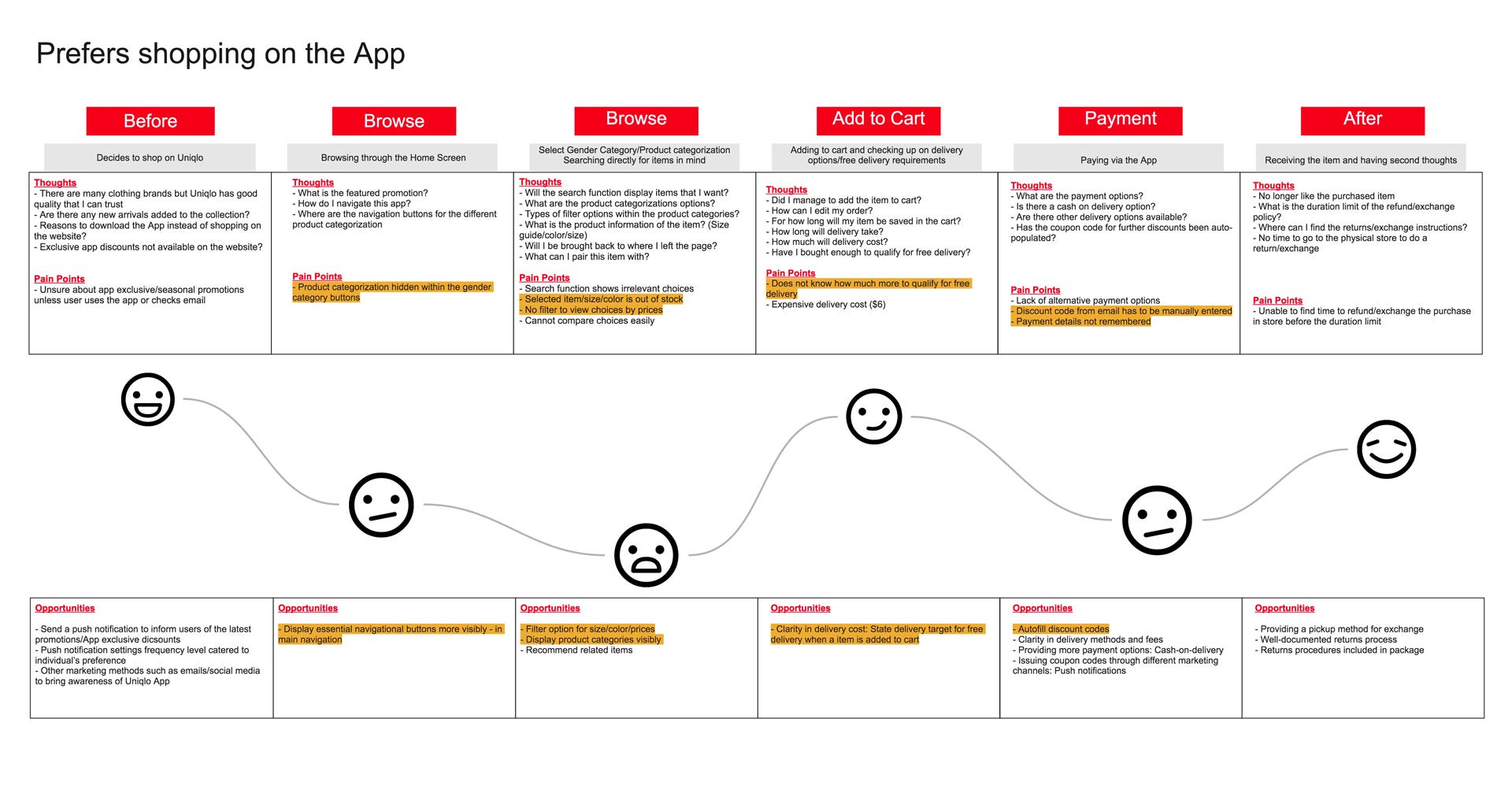

Persona 1 — Existing user of the app

Katie

prefers to shop online and is an existing user of the app. She wants

quick access to all the discounts and finds it difficult to find the

size and availability of the items she wants. While she is familiar and

comfortable using the app, she hopes the user experience can be

improved.

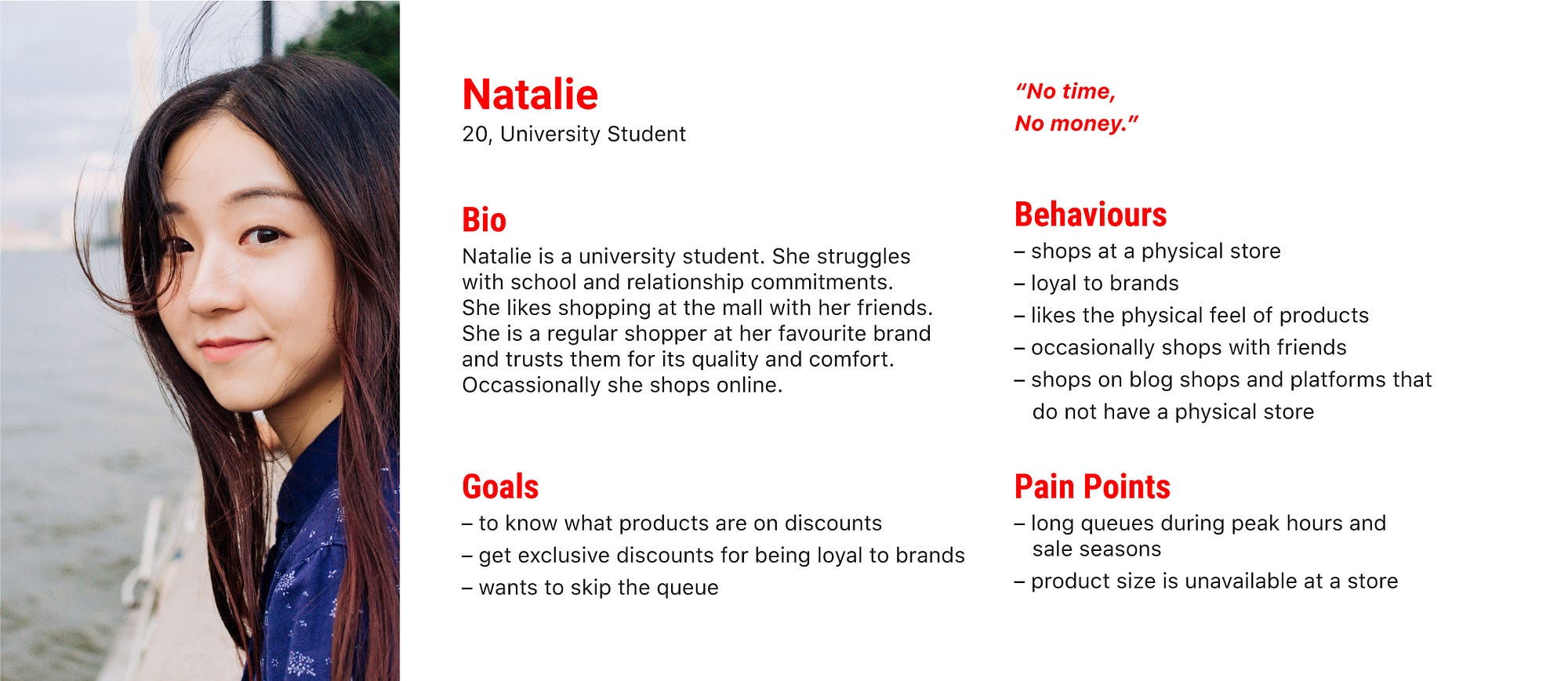

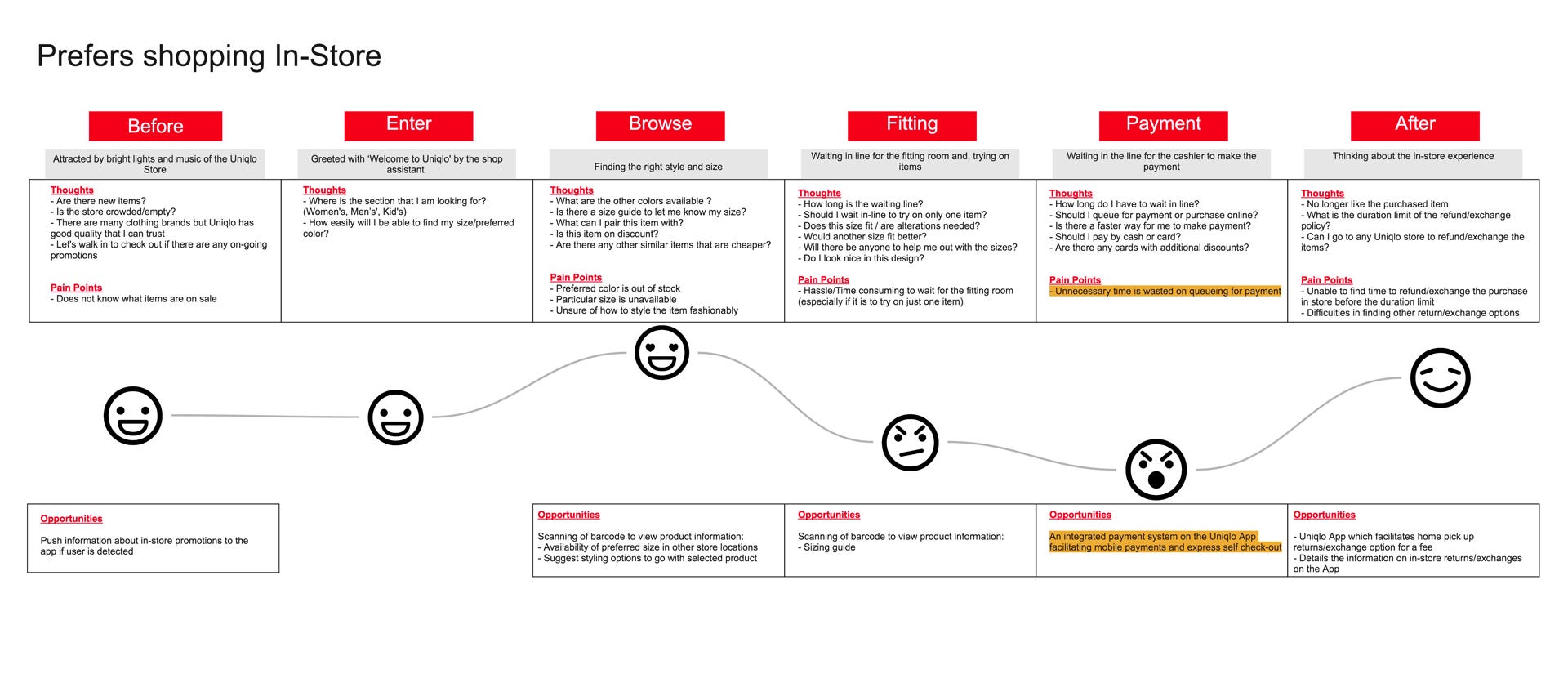

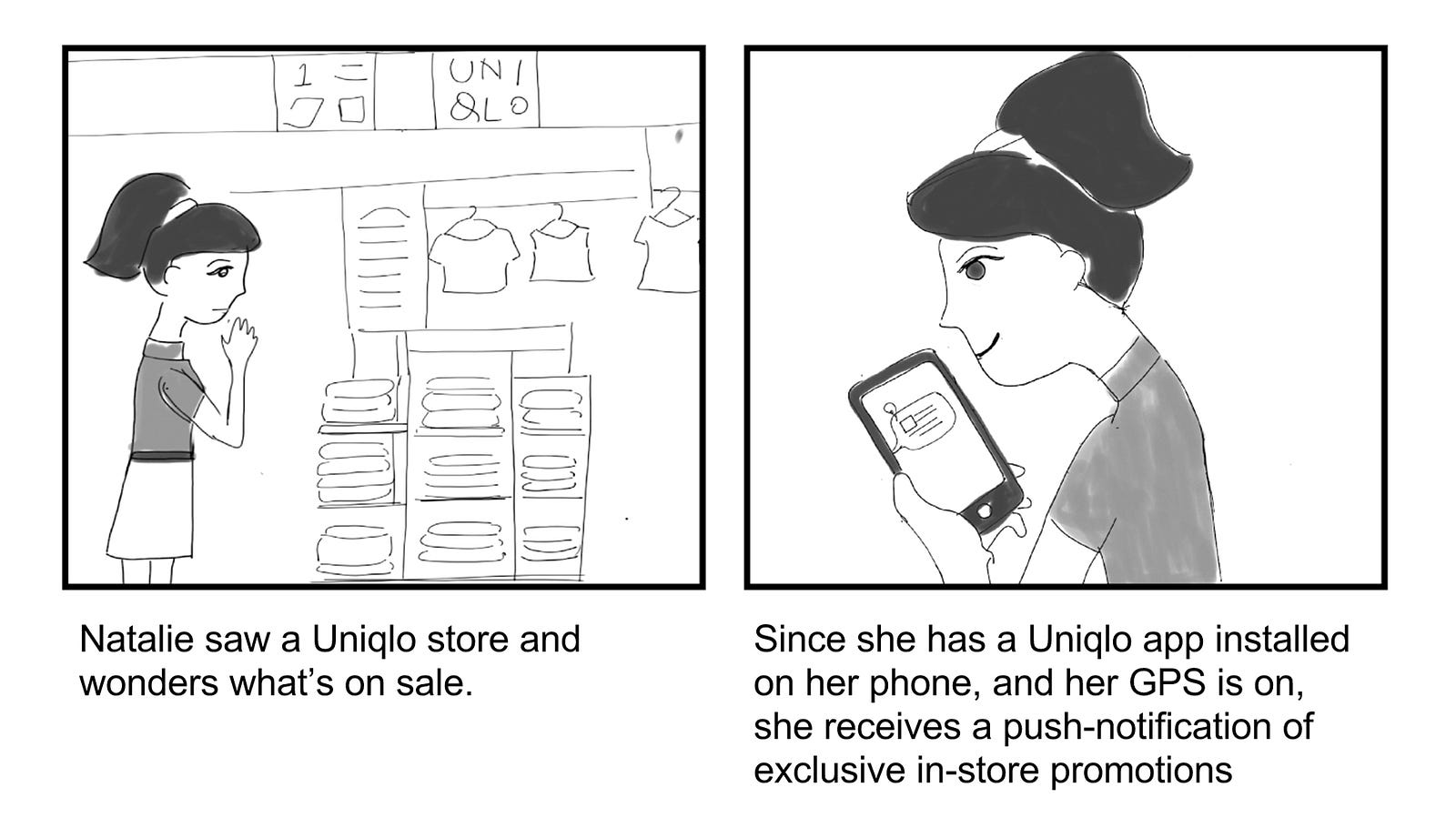

Persona 2 — Existing shopper and potential user of the app

Natalie

shops at the physical store and is not aware of the existing app. While

she enjoys shopping at the store, there are often long queues at the

payment counter. She may be a potential user of the app since she uses

other e-commerce apps to shop for clothes.

Potential project approaches:

- The redesign should not affect current users of the app. Navigation should be kept similar to the existing app and website.

- New features can be added to the app for current shoppers to use it in-store.

- Users should be able to access ‘Promotions’ quickly since it is a major feature of the brand.

- Increase awareness of the app through in-store posters and other marketing efforts.

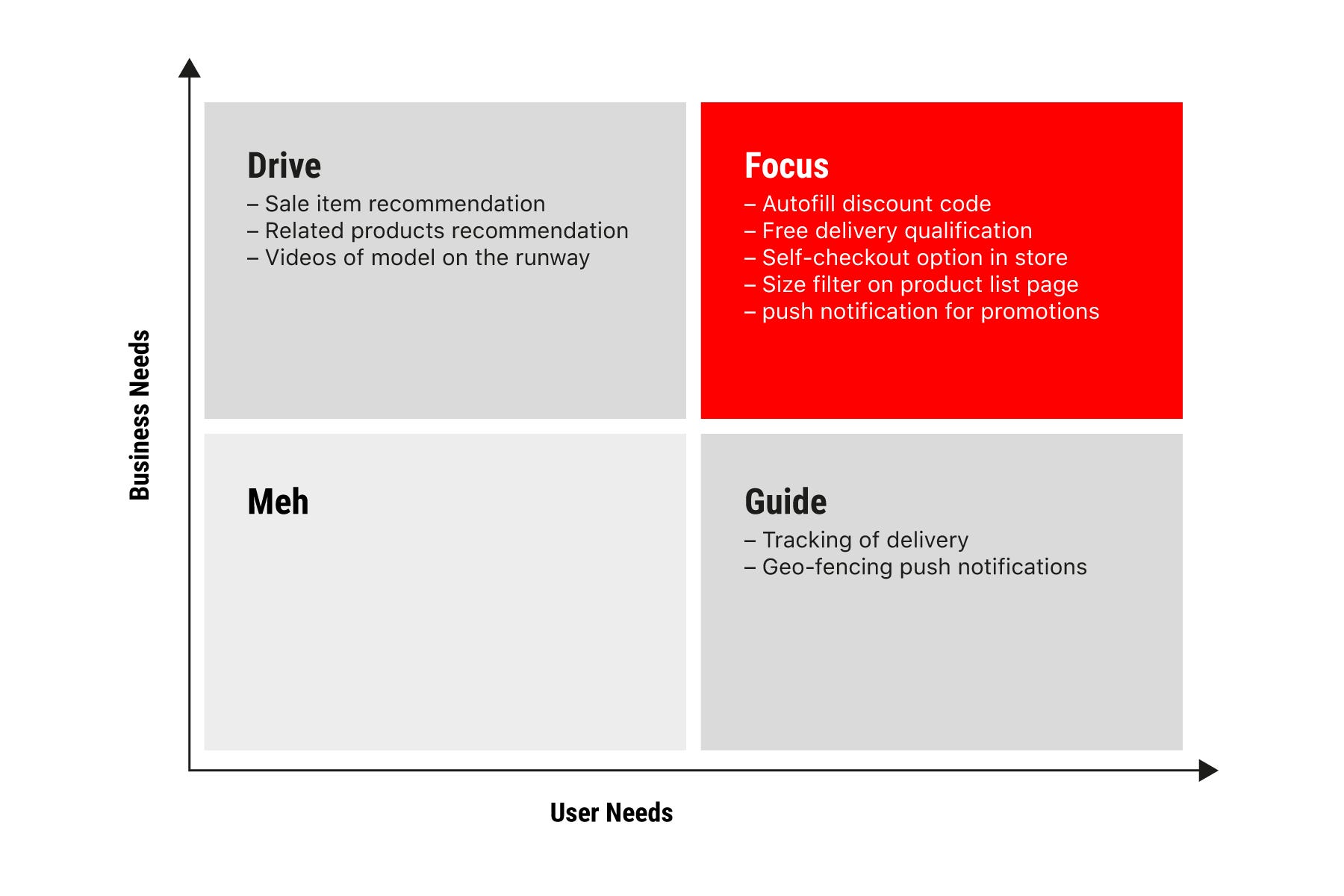

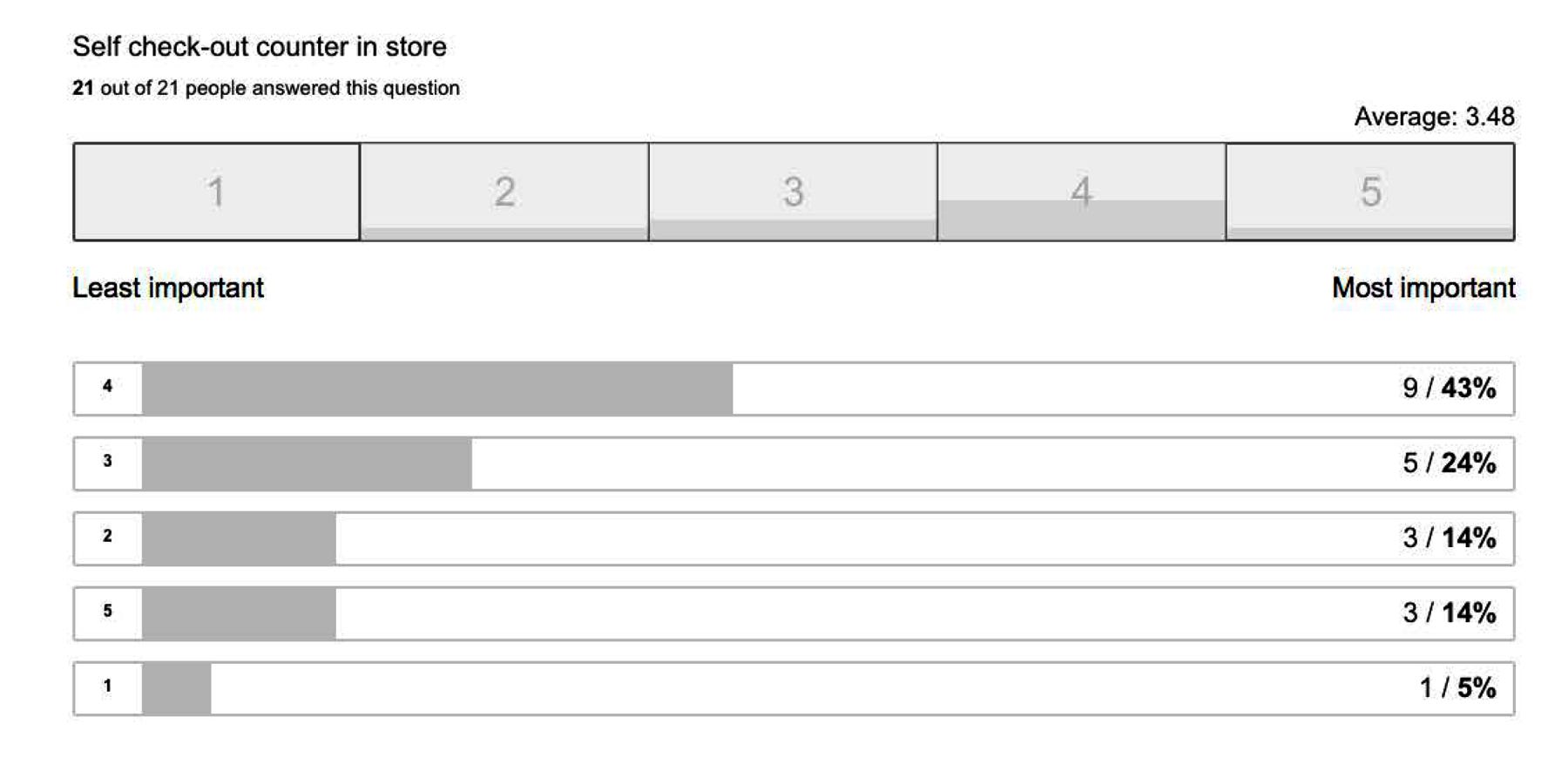

Feature Prioritisation Matrix

Through a design studio process, we came up with various new features we intend to include in the new app. To come out with a Minimal Viable Product (MVP, or Minimal Lovable Product, MLP)

we conducted an online survey to find out what users want on the app.

We looked at the features from the business perspective and organised

them according to our user and business needs. Features at the top right corner (the box in red) are the ones that should be included in the new version of the app.

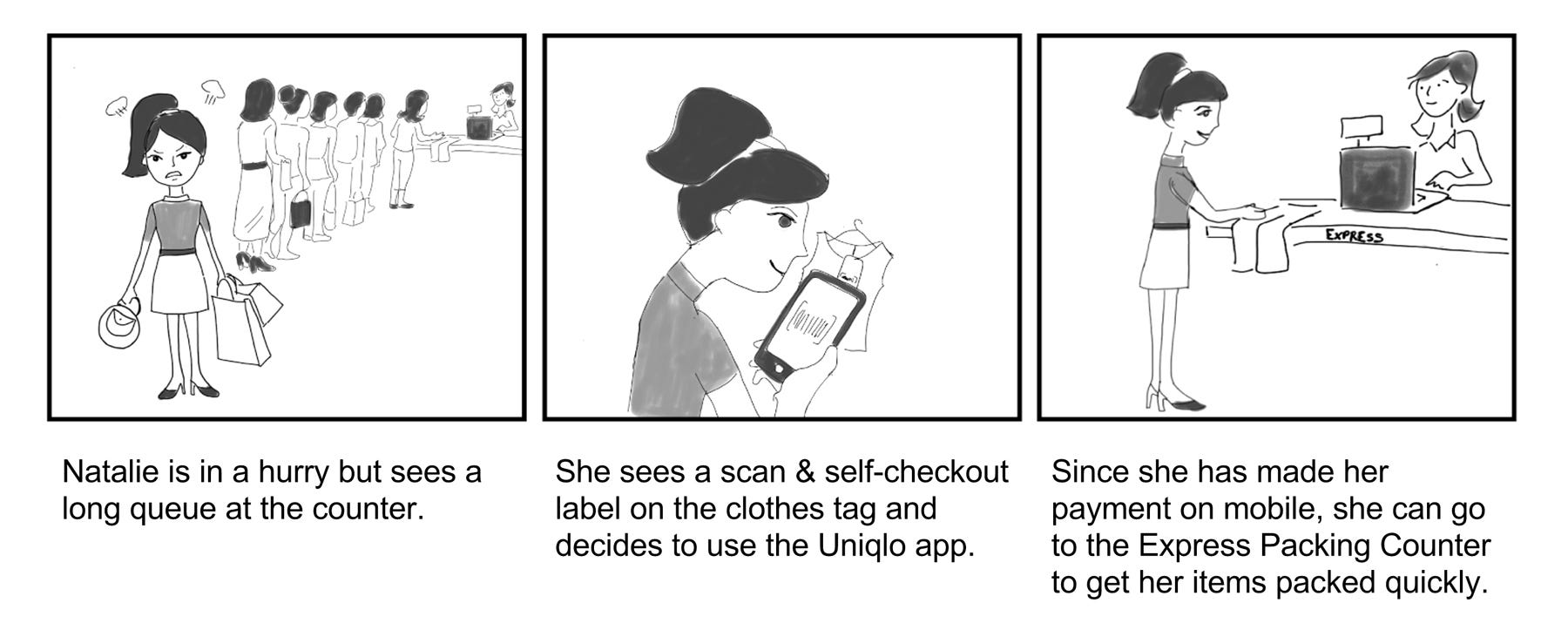

Storyboards

The new features are illustrated in storyboards, detailing the environment, scenario, and context where the app may be used.

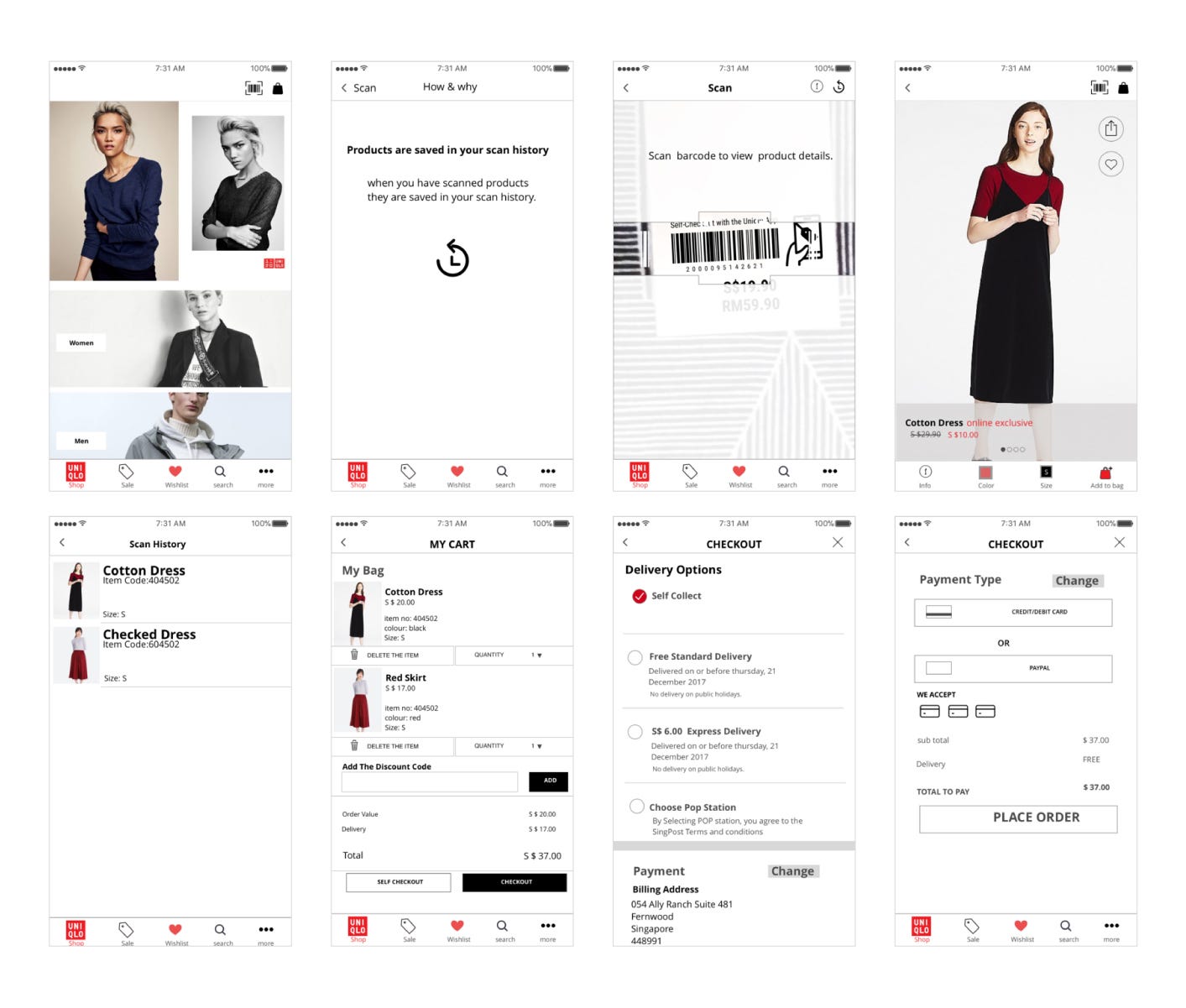

Mid-Fi Prototype & First Usability Test

Since

my team comprises two visual designers (myself included), we skipped to

a mid-fidelity prototype after doing quick sketches. Visuals of the

clothing may be important in helping users visualise the actual app.

The

version was used for testing with actual customers on our second trip

to the store. The purpose of the test is to determine if customers are

receptive to the new scanning and self-checkout feature.

Key findings from the usability test:

- Customers are able to identify the scan feature and its uses.

- Most customers are able to expect what will appear after scanning the product.

- However, they questioned the need to know more product information when they have the physical item on hand.

- Customers will use the self-checkout ‘only when there is a queue’. This is to be expected since most Singaporeans are more comfortable making payment by cash at a counter.

- However, most highlighted there they are slowly accepting mobile payments and self-checkout systems as part of the future retail experience.

- The wishlist feature was removed subsequently as users do not require the function.

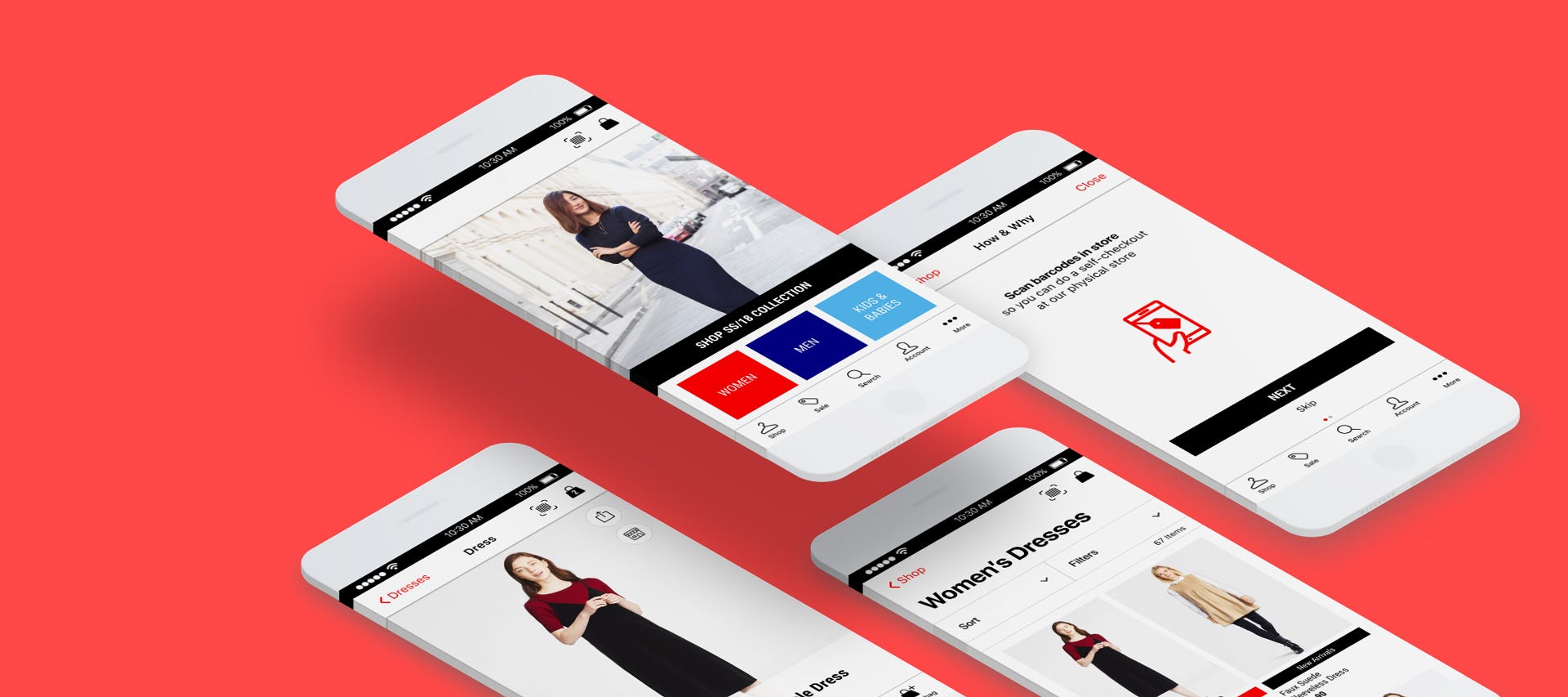

Hi-Fi Prototype

From

the usability test, we iterated a high fidelity prototype. The branding

was also enhanced in the design by using the right fonts and colours.

The interactive prototype can be viewed on InVision.

Feature Demonstration

Scan Feature

We created a video to show the new scan feature on the app since it was impossible to prototype the actual feature.

Delivery Target Bar

Another

feature on the app is an animated target bar for free delivery. This

will encourage users to spend more to meet the target while providing

greater clarity to the users.

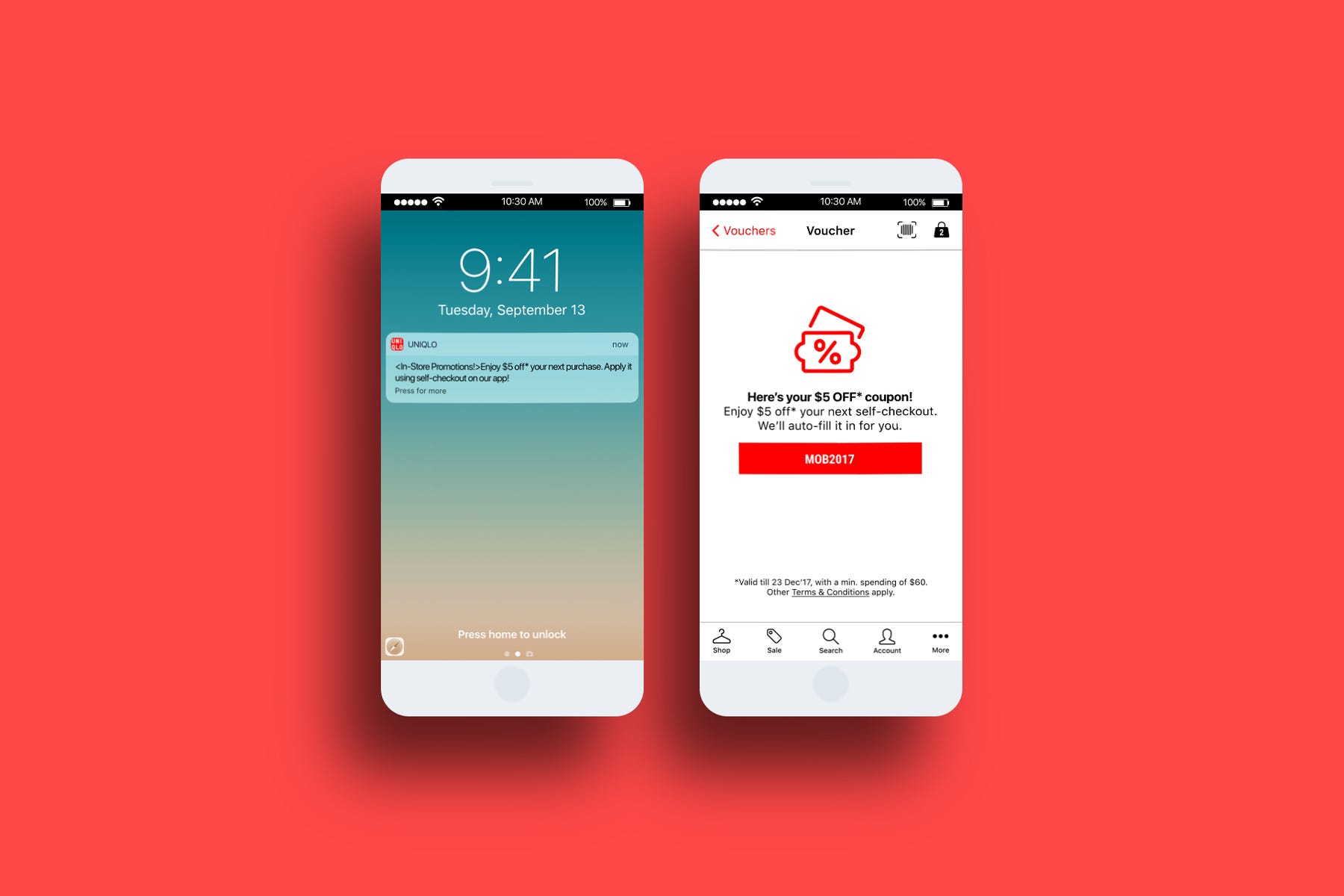

Geo-Fencing Push Notification

Users

will receive a mobile coupon through push notification when their GPS

indicates that they are near a store outlet. This will encourage them to

use the app for self-checkout.

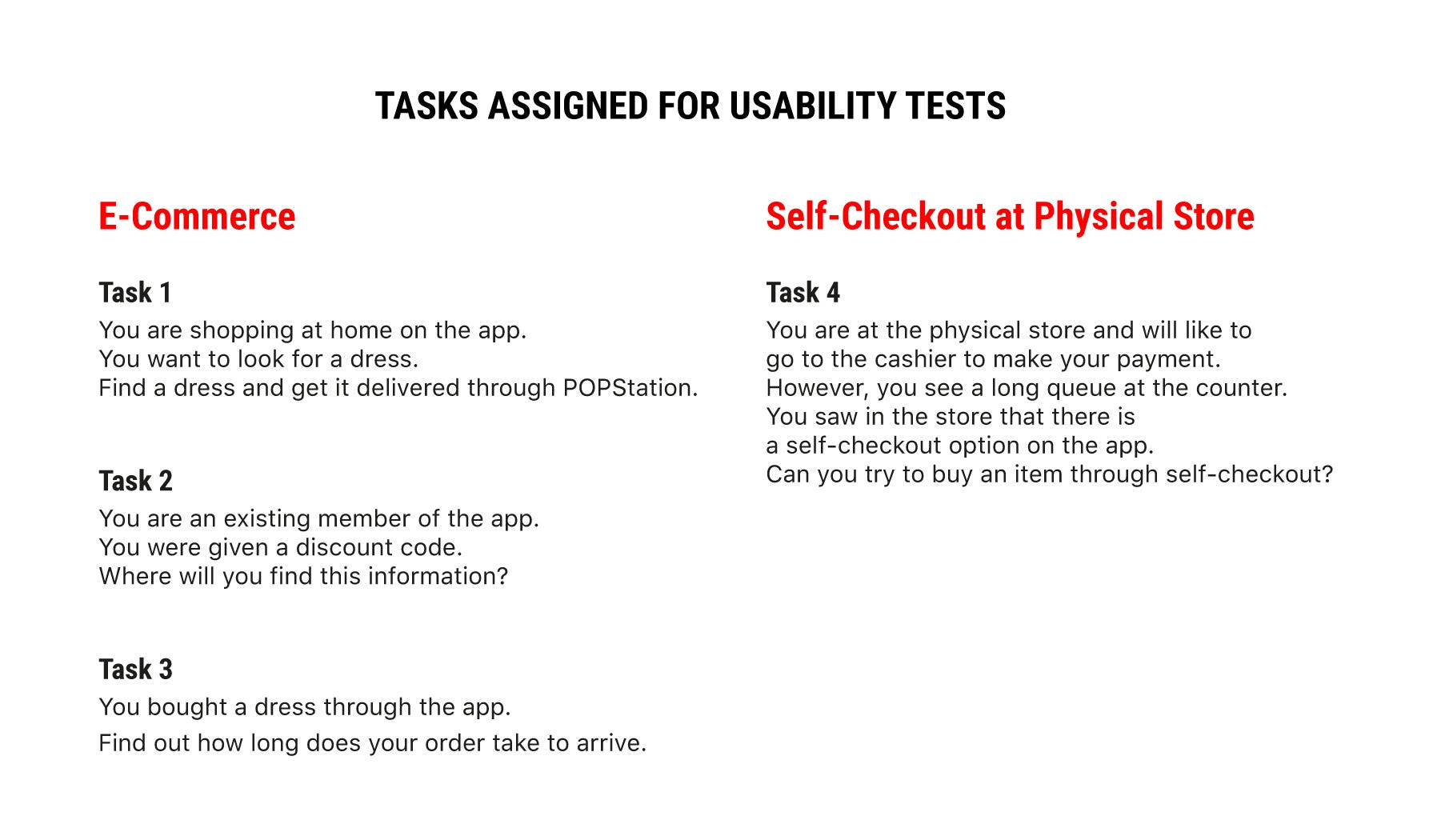

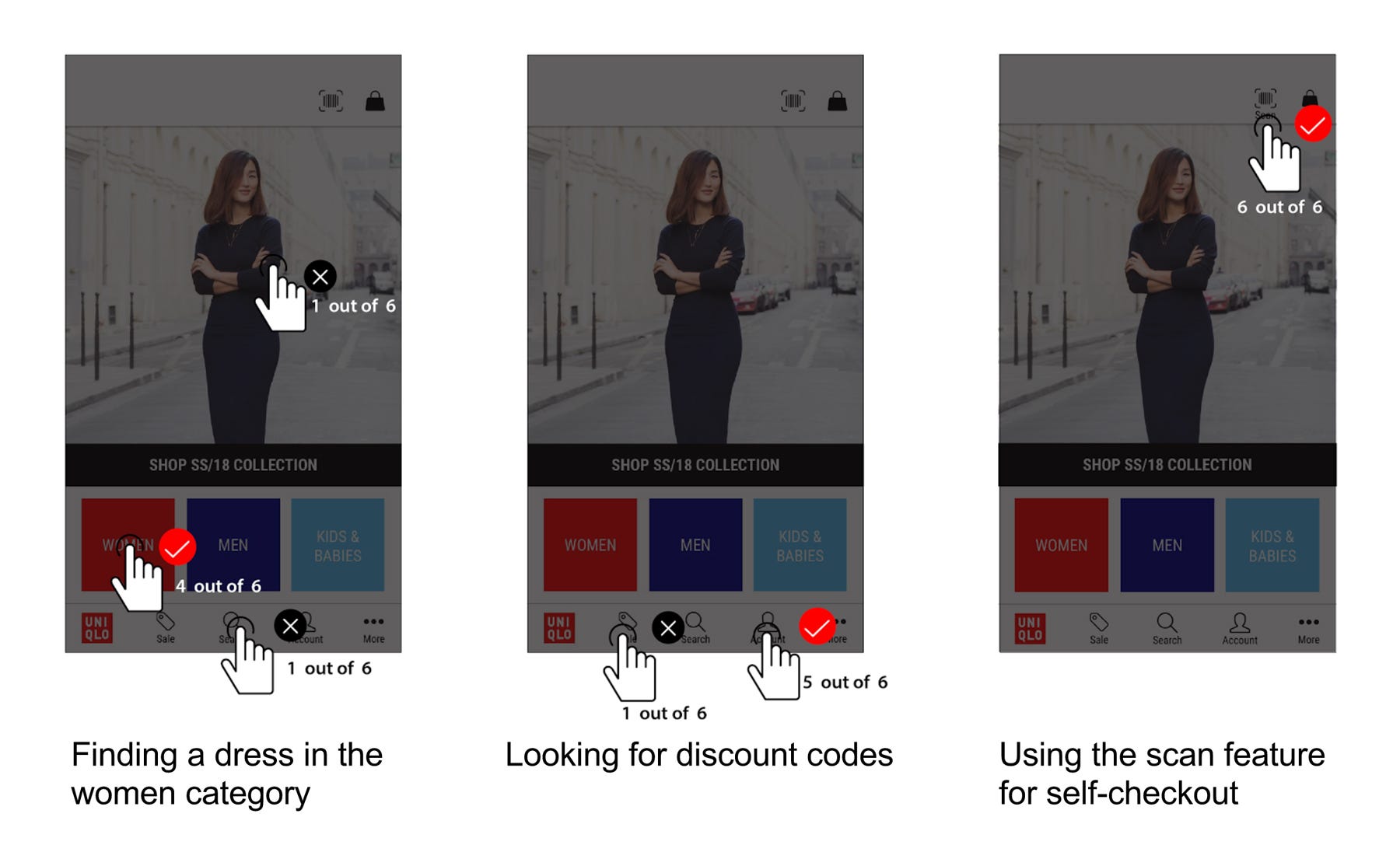

Usability Testing

Participants

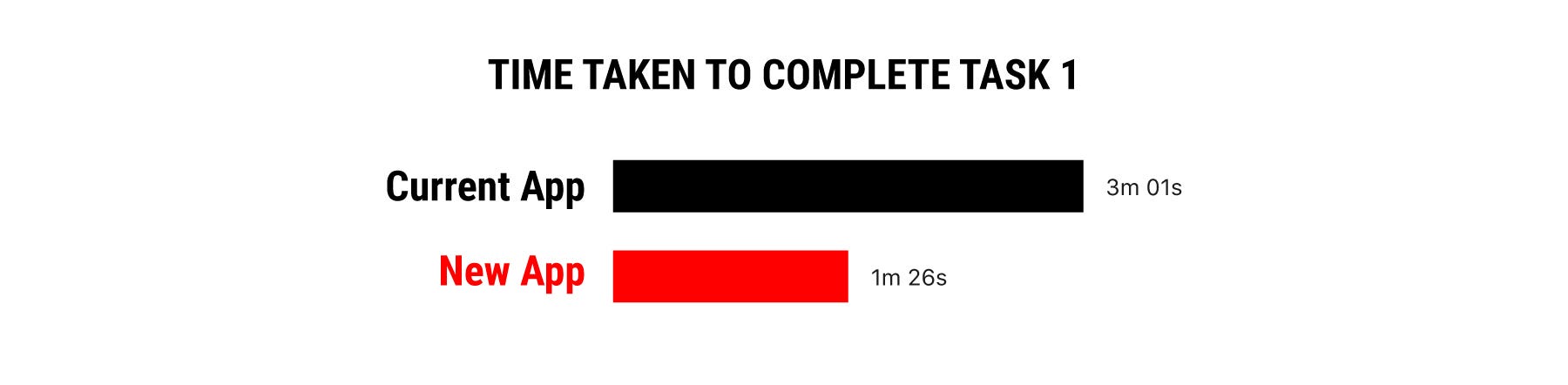

were given 4 tasks to complete. Task 1 was conducted on both the

existing app and the new app. The clicks for 3 of the tasks were

illustrated below.

To collect quantitative data, we timed users on how fast they took to complete the task on the existing app and new app. The new design allows the user to complete the task more efficiently.

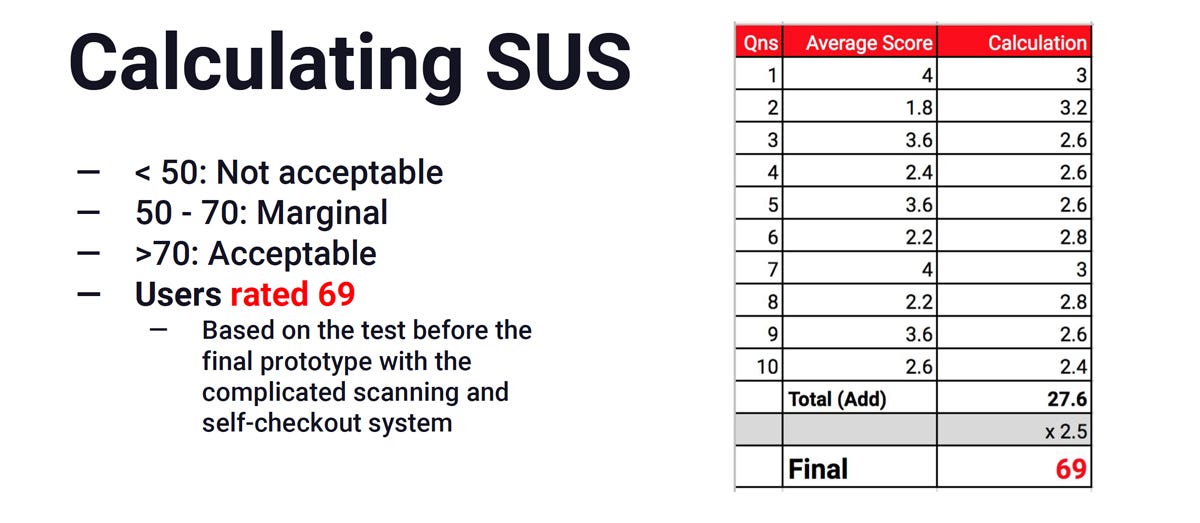

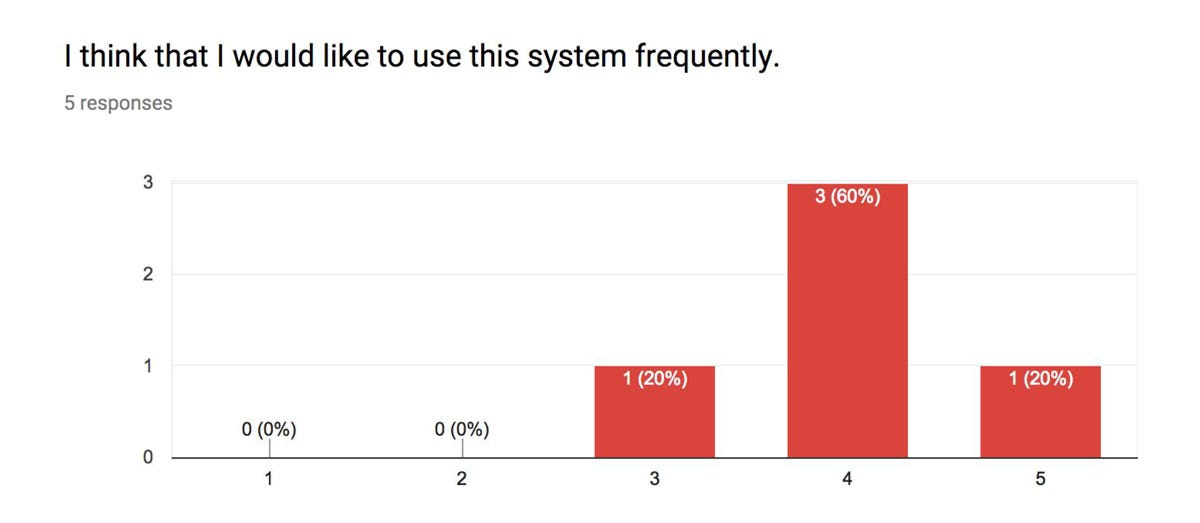

In

addition, we conducted a post-test survey to collect feedback from the

participants on their views of the new app. This was done with the System Usability Scale(SUS) test. The results were tabulated and calculated based on the method specified by the standardised test.

Results from system usability scale test:

- Users rated 69/100 (marginal) on their opinion of the new app.

- Although this is below the acceptable score (>70), it was not a bad score.

- The marginal score was due to the difficulty in performing task 4 (i.e. performing a self-checkout).

- Designing a self-checkout is a challenging task due to the lack of existing models to follow. Users need time to learn and accept self-checkout methods.

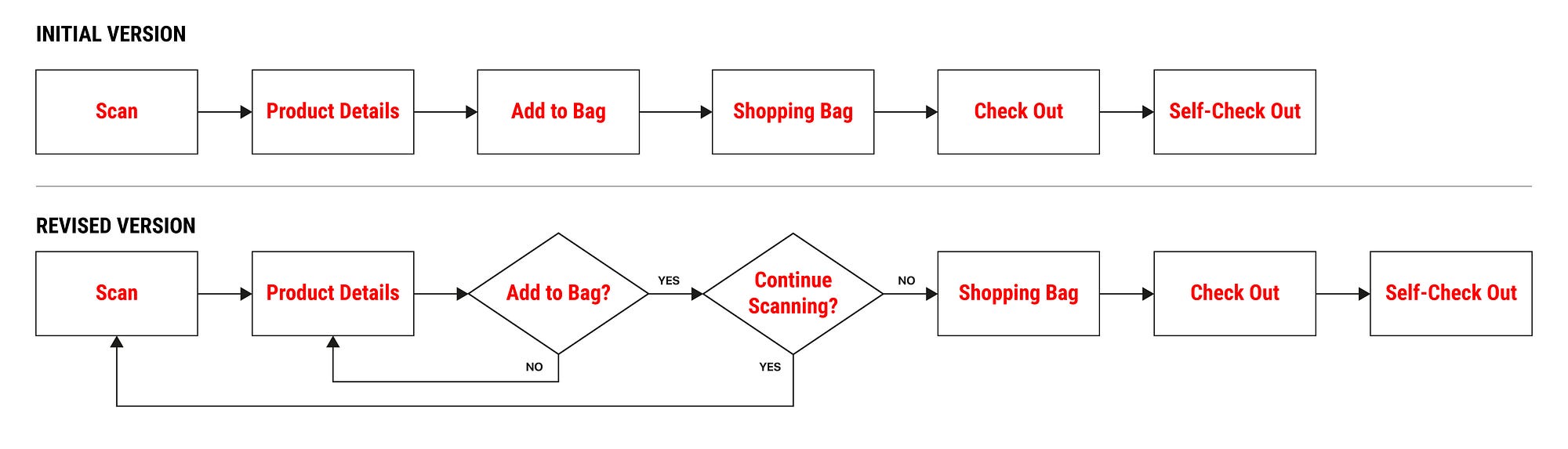

Design Iteration — Improving the User Flow

After the usability test, we discovered that users were confused by the product detail page after scanning the barcode. They assumed that the item was already added to the cart after the scan.

Scanning Products

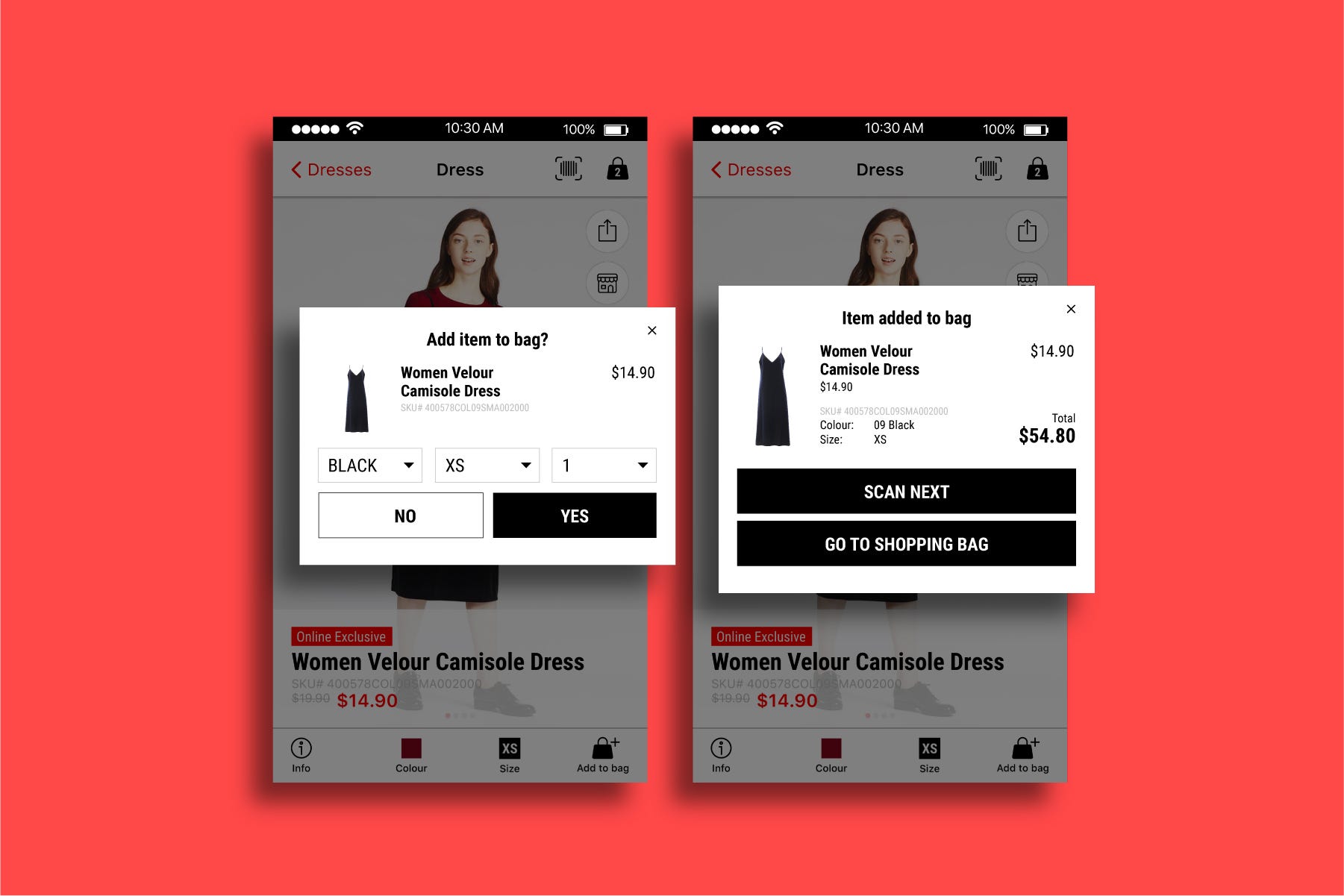

We made the process more informative for users by providing feedback on what is happening.

First, we prompt users if they want to add the item to the bag after

scanning the barcode. Next, we gave them the option to continue scanning

or proceed to the shopping bag. This provides more clarity to the user as they are provided with options to proceed to the next step.

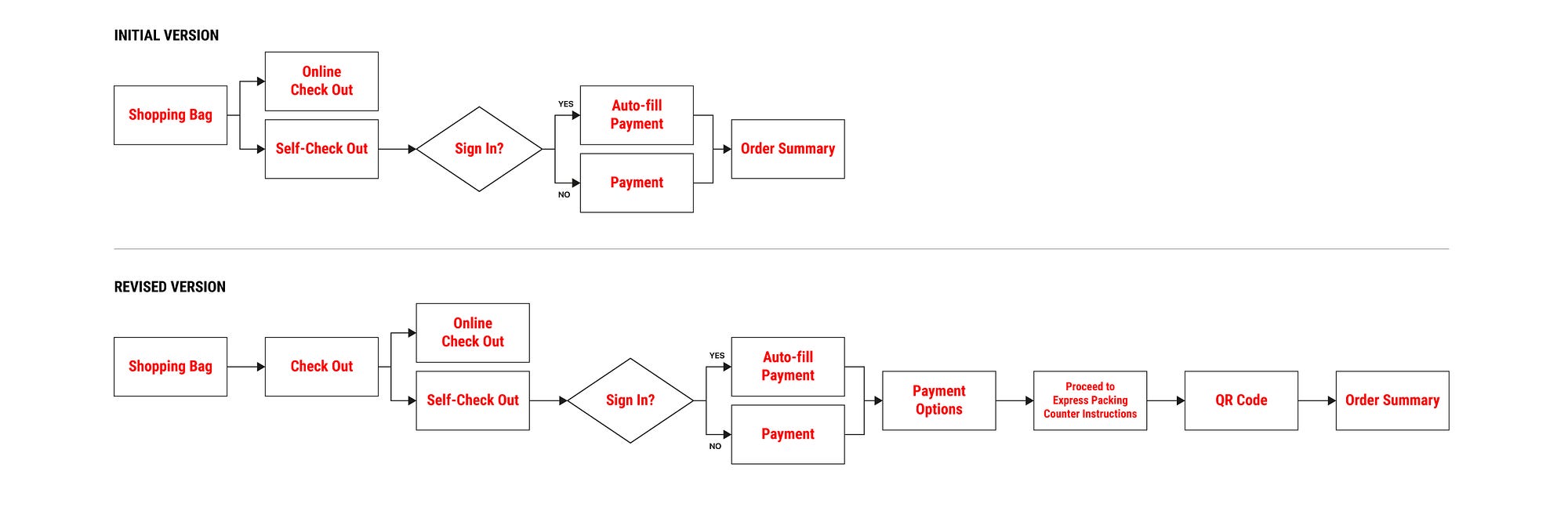

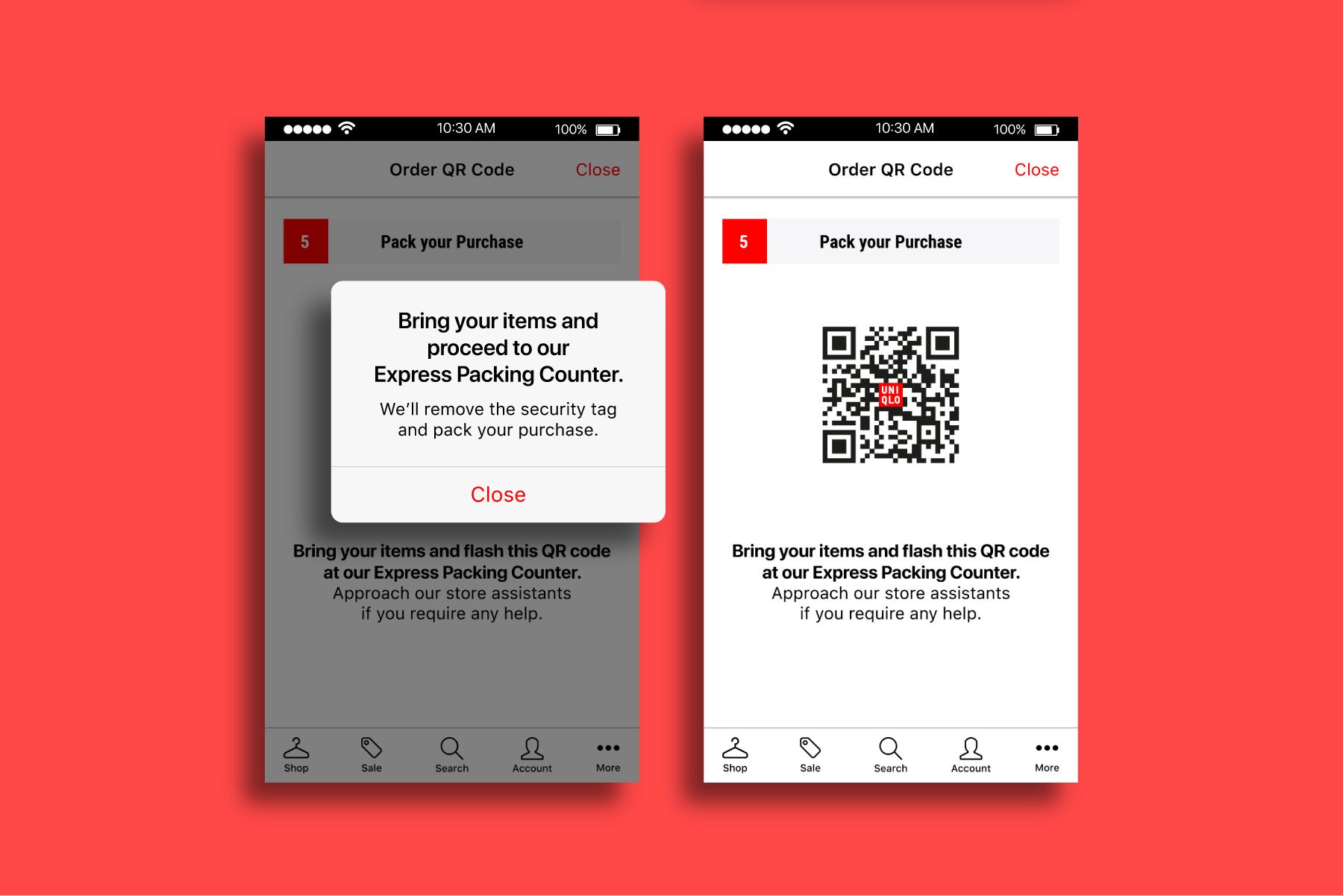

Self-Checkout

This is a case where a simpler user flow, may actually cause greater confusion to the user. With more steps inserted, users are more confident in performing tasks.

The revised self-checkout user flow may seem a lot more complicated, but provides greater clarity to users. This is because instructions are given to them to proceed to the Express Packing Counter to get their items packed, and the security tags removed. Without these instructions, users were unsure what to do after making a payment.

Promoting the App Usage

Through

our app redesign, we created opportunities where users can use the app

within the physical store. Hence, to encourage the usage, this should be

accompanied by various promotional materials around the stores.

For

example, the clothes tag can include a line to inform users that they

can scan and perform a self-checkout with the app. This can also be

included in the signages found throughout the store.

As

users have to get their items packed and security sensors removed, we

propose setting up an Express Packing Counter lanes that will be quicker

in serving these customers. This will help to bring about a greater

awareness of the app.

Future Steps

In the short term:

- We propose to include features that will help users to find what they need. For example, we can include an image search feature so that users can find a similar style.

- Personalised feed for signed in users based on gender and body size to suggest the right style and promotions.

In the long term:

- Align the current website with the new app after collecting user feedback for the new app.

- Rearrange products in the navigation based on knowledge of future product inventory.

Points to Note

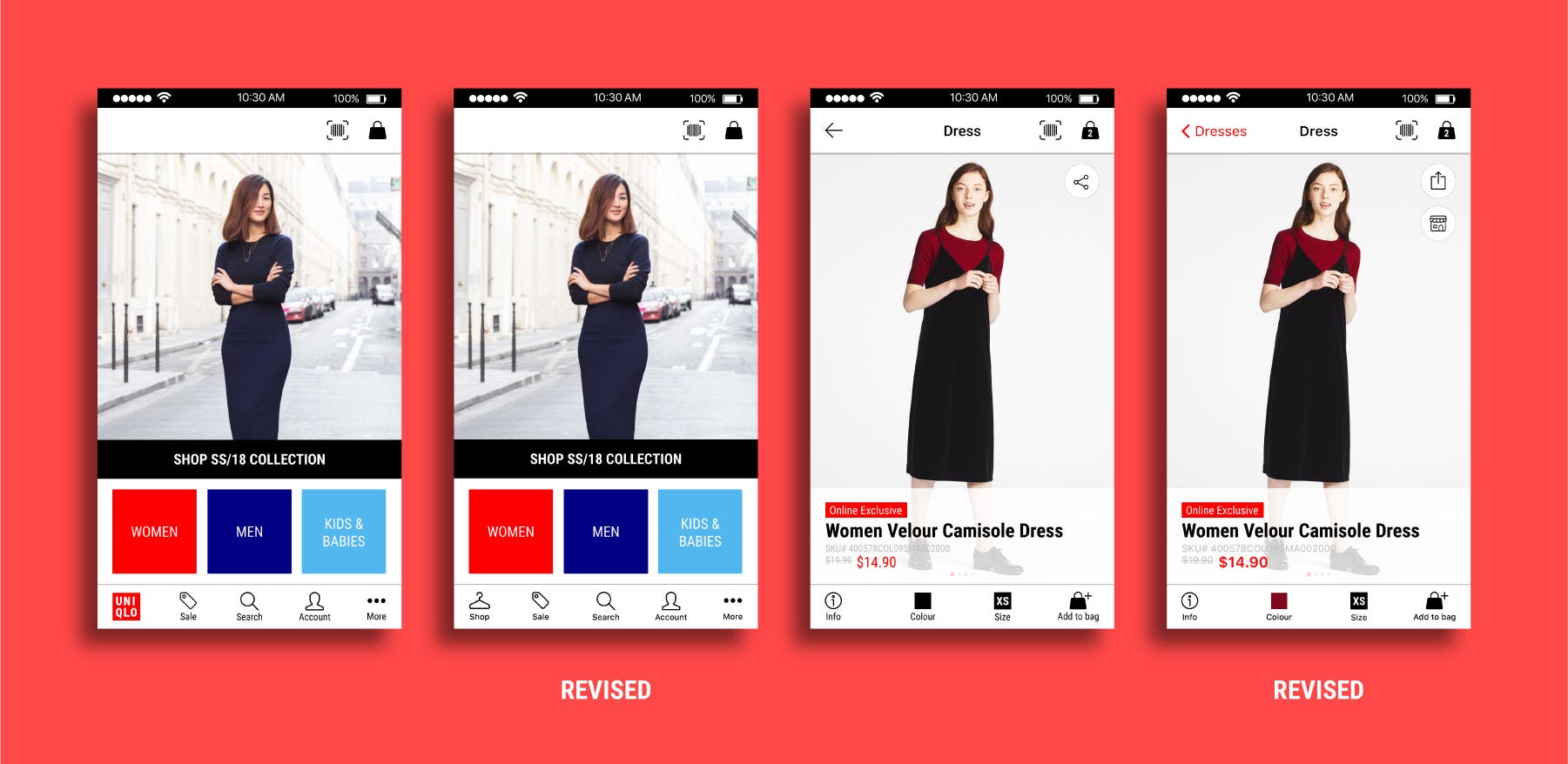

The design of the app in the InVision prototype does not follow the guidelines listed in the iOS Human Interface Guidelines. This was due to my unfamiliarity with iPhone app design. After studying the guide, I redesigned the app to match the style specified for iPhone 7.

The main difference is in the system font choice (SF Pro Display) and in the navigation labels. This is to ensure consistency throughout the iPhone.

Special thanks to:

Team mates, Parul Shukla & Cheryl Lee,

Instructor, Nie Zhen Zhi,

and Teaching Assistant, Wilson Chew

Instructor, Nie Zhen Zhi,

and Teaching Assistant, Wilson Chew